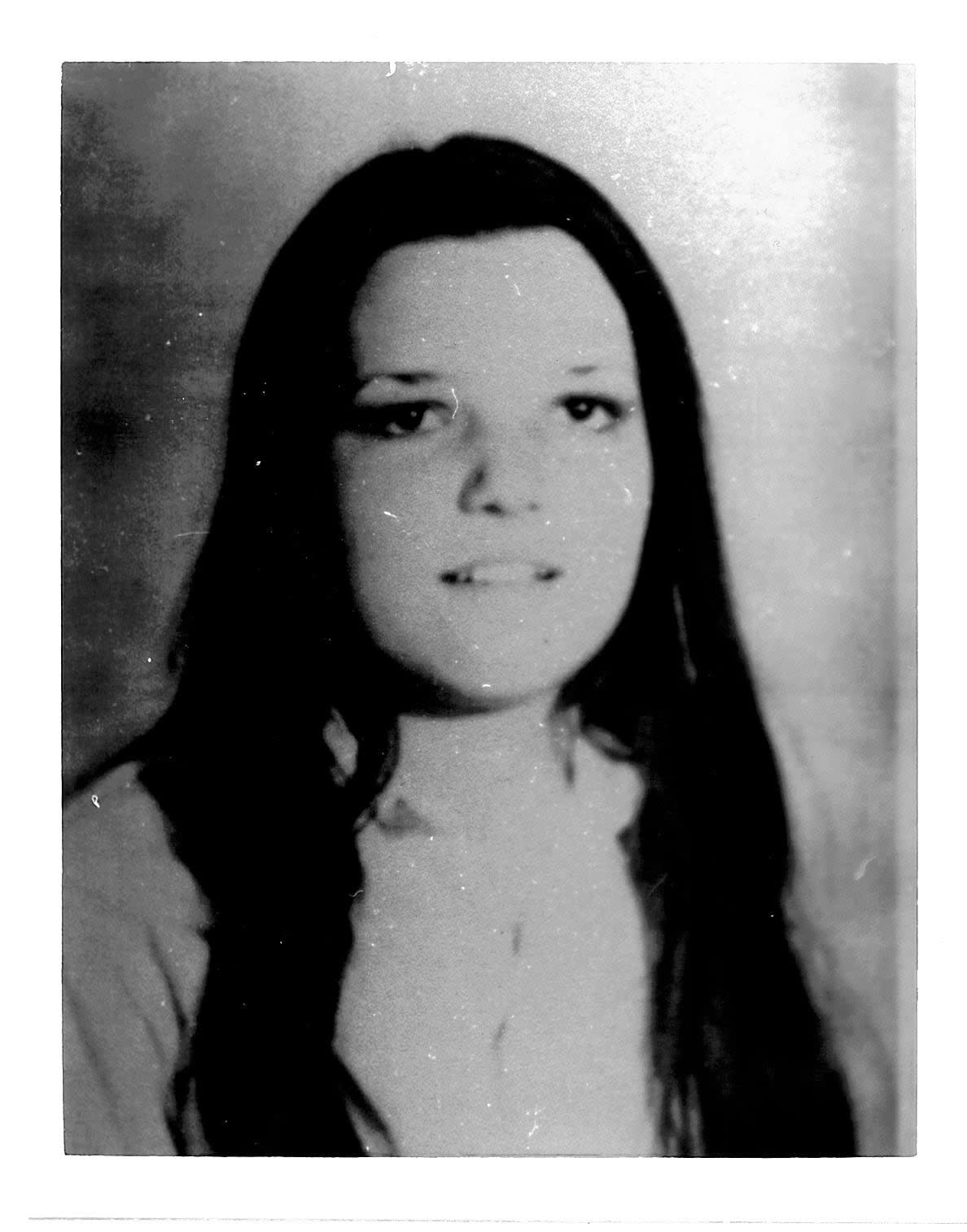

Windsor woman killed in 1970s cold case was a 'positive person,' family says

A Windsor woman killed in a cold case police only solved with the use of genealogy was 'a positive person who trusted people,' her family says."

Alberta RCMP announced last week that Gary Srery, an American serial killer and repeated sexual offender, was responsible for the death of Melissa Ann Rehorek, who was from Windsor and living in Calgary in 1976 when she went missing.

In a statement to the RCMP, Rehorek's family says they thank the team of investigators that found Srery.

"Our message is one about Melissa being a fun loving, adventurous and hard-working person. She was an honest, positive person who trusted people," the Rehorek family said. "She enjoyed travelling to Banff for her love of nature but also to travel for her curiosity about seeing Canada.

"Our family appreciates all of your help."

LISTEN: The evolution of DNA evidence that has change the field of forensic science

Srery was also responsible for the deaths of three others: Eva Dvorak and Patricia McQueen, both 14, and Barbara MacLean, 19. He died in an Idaho prison in 2011 while serving a life sentence

The families of all of the victims asked not to be contacted by the media.

RCMP Insp. Breanna Brown with images of Gary Allen Srery. Police say Srery, who died in 2011, was responsible for the deaths of four young victims in Calgary in the 1970s. (Trevor Wilson/CBC)

Srery — born in 1942 in Oak Park, Ill. — was identified through the use of DNA and criminal databases that helped trace his family tree.

RCMP said his name had never surfaced over decades of investigation, and that only DNA evidence and an ancestry investigation linked him to the killings.

DNA profiles from the cases went without a hit for over 20 years. Then in 2021, police formed a partnership to use Investigative Genetic Genealogy (IGG) in an attempt to identify the suspect. The database relies on genetic samples to identify potential relatives of unidentified suspects.

They worked with the RCMP lab and Parabon NanoLabs to develop a single profile that was then uploaded to GEDMatch and FamilyTreeDNA.

Other cold cases solved with geneology and DNA

It's not the only cold case solved with the use of DNA and genealogy with a Windsor connection. Windsor police said in 2023 they identified the man they believe killed Ljubica Topic, a six-year-old Windsor girl who was abducted, sexually assaulted and murdered in 1971.

Ljubica Topic, a six-year-old Windsor girl was murdered in 1971. (CBC News)

Police say they used publicly-available genetic data and DNA from the crime scene to identify Topic's former neighbour, who has died, as the killer and closed the case in 2019.

The practice of using investigative genetic genealogy isn't yet widespread, especially compared to other police tools like fingerprints, said Natalie Delia, an associate processor in criminology at the University of Windsor.

"All of this work with DNA is definitely less than half a percent of crimes."

As an expert, she says she approaches this and many technological advances in criminology with "ambivalence."

She says on one hand, it's a great tool for justice and accountability, on the other, there are ethical questions around the use and storage of DNA information.

Natalie Delia is an associate professor of criminology at the University of Windsor. (Michael Hargreaves/CBC)

Delia said the default right now for major companies that store DNA like this is that privacy can't be "trampled" over — law enforcement needs a reason and a court order, and then companies will comply.

"But it's not like your DNA is just sort of available for law enforcement," she said. "But still, by putting your DNA out there, it is now out there."

Delia says there needs to be laws on the issue, saying that right now, it's governed by private companies and their terms and conditions.