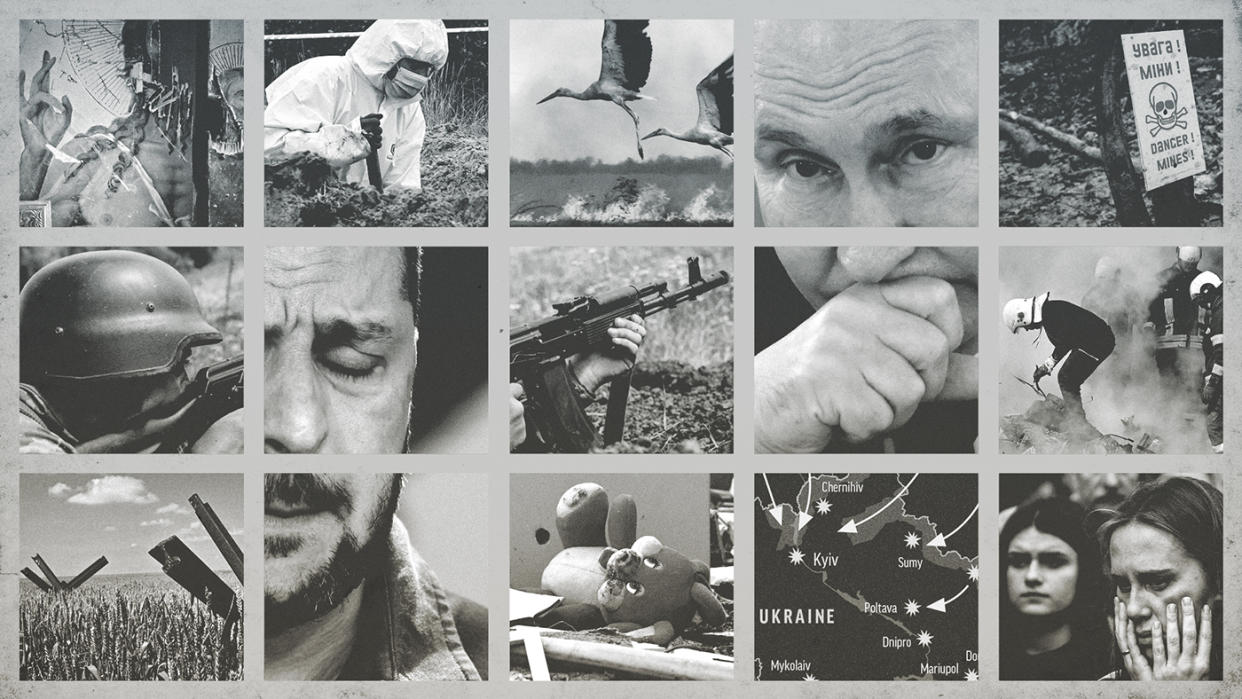

Who will win the war in Ukraine?

Ukraine is facing "its worst crisis since the war began", as Russian forces concentrate their attention on Kharkiv, wrote the BBC's international editor, Jeremy Bowen.

So far, Russia "has concentrated most of its offensive pressure in Ukraine's east", said Reuters, but on 10 May Russian troops crossed the border in the northeastern Kharkiv Oblast, home to Ukraine's second city.

Ukrainian commander-in-chief Colonel General Oleksandr Syrskyi has identified two main lines of attack forming in the north of the Kharkiv region, including around the border town of Vovchansk, "where there has been street fighting", said Reuters.

Officials told the agency that Ukrainian forces "were continuing to strengthen their defensive lines" and Russia "still lacks the troop numbers to stage a major push in the area".

But although Kyiv and its allies may well be correct that Russia only has the capacity to take "limited territory at a high cost in men and materiel", said Bowen, without a "qualitative change" in Ukraine's fortunes, the Russian offensive will continue to "grind its way deeper into this war".

What has happened recently?

In late April, the US committed to an aid package worth $61 billion (£49 billion), "after months of dithering" in Congress, said The Economist. During that process, Russia renewed its offensive to devastating effect, taking the eastern city of Avdiivka in February and making slow but consistent gains in the Donetsk region since then.

The first shipments are now arriving on the frontlines, but the prolonged wait will make reversing recent Russian gains even more of a challenge for Ukraine's beleaguered forces. White House national security adviser Jake Sullivan acknowledged that "it's going to take some time for us to dig out of the hole that was created by six months of delay" in Congress.

The recent gains have come at a steep cost for Russia, too, said The New York Times. Casualty estimates circulating among military analysts, pro-Russian bloggers and Ukrainian officials suggest that Moscow "lost more troops taking Avdiivka than it did in 10 years of fighting in Afghanistan in the 1980s". And the death tolls on both sides of the conflict are continuing to mount.

How many Russian and Ukrainian troops have died in the conflict?

True casualty figures are "notoriously difficult to pin down", said Newsweek, and "experts caution that both sides likely inflate the other's reported losses".

Earlier this month, an investigation by the BBC's Russian unit was able to identify 52,155 named Russian military personnel who have died in the conflict so far, but used statistical data on excess deaths to suggest that the true figure could be more than 100,000. Emmanuel Macron's foreign minister, Stéphane Séjourné, said France was working with an estimate of 150,000 Russian military deaths.

In February, Volodymyr Zelenskyy said 31,000 Ukrainian soldiers have been killed since the beginning of the invasion. No further official figures have been released since then, but The New York Times reported in May that the Ukrainian military was "overloaded with casualties and unable to account for thousands" of soldiers missing in action.

What does victory look like for each side?

Before Russia launched its invasion in February 2022, Putin outlined the objectives of what he called a "special military operation". His goal, he claimed, was to "denazify" and "demilitarise" Ukraine, and to defend Donetsk and Luhansk, the two eastern Ukrainian territories occupied by Russian proxy forces since 2014.

Another objective, although never explicitly stated, was to topple the Ukrainian government and remove the country's president, Zelenskyy. "The enemy has designated me as target number one; my family is target number two," said Zelenskyy shortly after the invasion. Russian troops made two attempts to storm the presidential compound.

Russia shifted its objectives, however, about a month into the invasion, after Russian forces were forced to retreat from Kyiv and Chernihiv. According to the Kremlin, its main goal became the "liberation of the Donbas", including the regions of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia – but Moscow has made little progress in achieving this aim.

Ukraine's main objective is the liberation of its occupied territories. That includes not just those held by Russia since the February 2022 invasion, but a return to its internationally recognised borders, including Crimea.

Can Ukraine win the war?

After weeks of blistering aerial bombardments of Ukrainian positions, there's a "great risk" of the defensive lines "collapsing wherever Russian generals decide to focus their offensive", said Politico.

A senior Ukrainian military source told the news site: "There's nothing that can help Ukraine now because there are no serious technologies able to compensate Ukraine for the large mass of troops Russia is likely to hurl at us."

Earlier this year, Zelenskyy lowered the age of military conscription in Ukraine to 25 in an attempt to boost troop numbers. But conscription remains a touchy topic in Ukraine, and officials have had to tread lightly amid dwindling enthusiasm for military service. "We don't only have a military crisis – we have a political one," one of the officers speaking to Politico warned.

Ukraine's "inherent weakness is that it depends on others for funding and arms", wrote Bowen for the BBC, while Russia – in addition to an advantage in raw manpower – "makes most of its own weapons". And while the US continues to impose restrictions on how its weaponry is used in Ukraine, including a ban on strikes within Russia, Moscow "is buying drones from Iran and ammunition from North Korea" with no such limitations.

Vladimir Putin is reported to be "ready to halt the war in Ukraine with a negotiated ceasefire that recognises the current battlefield lines", said Reuters, an arrangement which would "leave Russia in possession of substantial chunks of four Ukrainian regions". But Zelenskyy has repeatedly emphasised that any peace deal must include the withdrawal of Russian forces to behind pre-invasion borders, meaning the prospect of any ceasefire or peace talks currently "seems remote".

On 15 and 16 June, representatives from more than 80 countries are to take part in a summit in Switzerland aimed at establishing a framework which could lead to lasting peace.

However, Russia is not invited to the conference, making it "more of a solidarity exercise than a true negotiation", Sergey Radchenko, professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, told European news website Euractiv.

Any serious ceasefire or peace deal will be a "protracted negotiation between a very limited number of parties", he said. "At the moment what we are seeing is a tendency towards a short PR event with a large number of parties, except the ones that matter."