Women Tend to Vote for Democratic Presidential Candidates More Than Men Do. Here’s How That Gender Gap First Came to Be

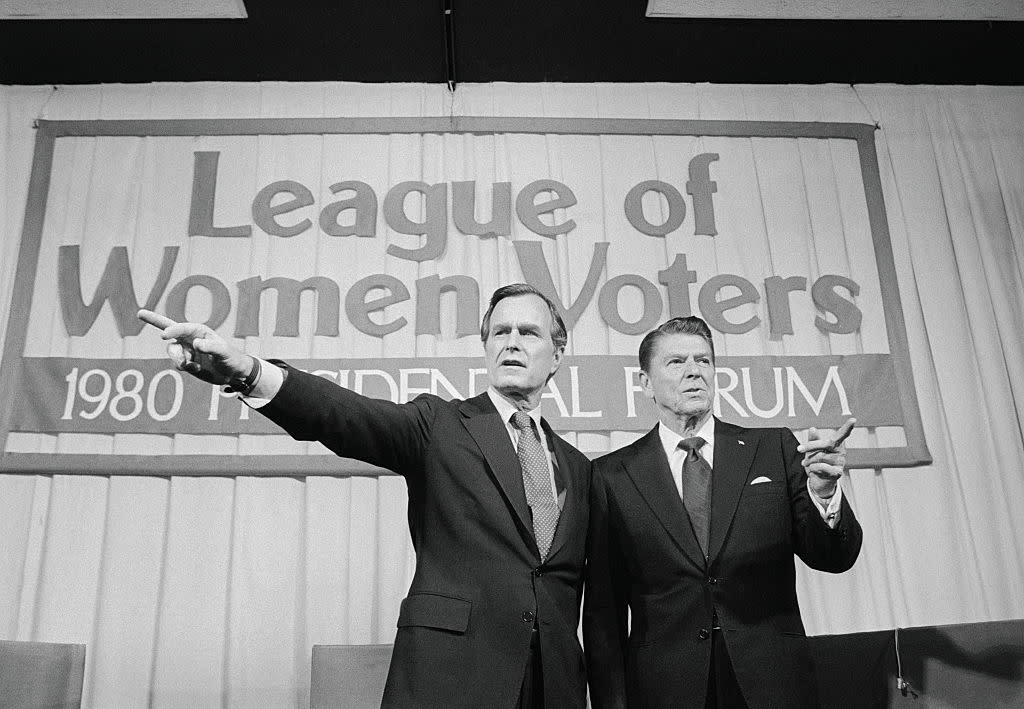

George Bush (L) and Ronald Reagan before the start of a debate before the League of Women Voters Forum in Houston in April 1980 Credit - Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

As the electoral odds facing President Donald Trump and former Vice President Joe Biden have continued to diverge in national and state polls, there’s at least one area where the divergence has been particularly striking: By early October, one national poll had Biden leading Trump by over 20 points among registered female voters; Trump and Biden were tied among likely male voters. Other October polls had Biden up an average of 25 points among women—which, if it holds, would be a record in modern elections.

Nationally, women in the U.S. have had the vote for 100 years. For the last 40 of those years, they have voted for the Democratic presidential candidate in greater numbers than men have. (Notably, this does not mean a majority of women always vote for the Democrat.) This remarkably durable voting pattern may not be a surprise this year, but it shook Republicans when it emerged in 1980—and examining the two parties’ responses to this voting pattern can help us understand the shape of American politics today.

It took 60 years for women to vote in the same proportion as men. In 1980, for the first time since the passage of the 19th Amendment, women voted at the same rate as men. That was also the first time they voted noticeably differently from men. Ronald Reagan beat Jimmy Carter by almost 10 percentage points in the 1980 presidential election. Among women voters, however, Reagan won by only a single percentage point (46% of the vote, compared to Carter’s 45%). Democrats immediately moved to claim the gender gap for political mileage even as Reagan’s supporters struggled to understand what had happened.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Some relatively obvious things had changed for the Republican Party in 1980. The party removed support for the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) from its platform that year, after 40 years of relatively consistent support. Further, for the first time since Roe v. Wade was decided, there was a clear divide between the candidates on support for abortion rights, as Reagan was on the record supporting a constitutional amendment banning them. Interestingly, however, it was not at all clear these issues were driving the new gap in voting. Reagan’s own pollsters pointed out that a majority of both men and women supported the ERA and reproductive rights, but they still diverged in support for Reagan. What then was driving the gap?

In 1982, Democrats picked up 26 seats in the House of Representatives. Political analysts attributed this loss to the GOP’s continuing failure to win over women voters. A few days later, Reagan pollster Ronald Hinckley presented the administration with a memo analyzing the new voting pattern. The memo argued that Republicans’ biggest problem was appealing to non-married women. Hinckley wrote, “The most dramatic change in America during the 1970s was the increase in families headed by single women.” Notably, Reagan pollsters warned the Administration against writing off the gender gap as the result of racial division. While there were a disproportionate number of Black women among non-married women, the group overall was 70% white.

In the end, the explanation Hinckley offered was predictable and mundane: women were voting their economic interests. The problem was that Reagan’s policies—cutting Social Security and restricting access to welfare, for example—fell “hardest” on women. The report explained, “Fear of losing government benefits appears to be causing women to oppose the Administration. Controlling for receipt of government benefits, the gender gap does decrease.” The two parties’ increasing polarization around cultural issues might have been grabbing headlines, but women were looking at their wallets when deciding who to vote for, and one party was clearly doing more for them.

Reagan spent quite a bit of time and energy in 1982 and 1983 trying to appeal to women. He nominated women to his cabinet and put energy into promoting accomplishments like expanded tax credits for childcare. He was not, however, willing to address the issue that his pollsters had identified as driving the gender gap; he continued to cut government benefits. This choice about which issues to use to try to woo women and which to ignore flowed both from Reagan’s conservative ideology and from the recognition by his advisors that women were not a unified bloc. Reagan never really tried to win over Black women, for example; instead, he focused on white homemakers and professionals and tried to persuade those women that his economic policies were in their best interests. In 1984, the gender gap narrowed but did not disappear. Reagan won anyway.

Arguably, for the Republican party, one lesson of 1980 and 1984 was that a Republican could win without fully closing the gender gap. The GOP has continued to narrowly target very specific groups of women. We have heard about soccer moms, security moms, mama grizzlies and this year, suburban moms. Appeals to these demographic slices have followed the Reagan playbook: nominating women to fill key roles and focusing on substantive issues that on their face have little to do with gender—for example, national security—but which a specific demographic of women care very deeply about.

At the same time, Democrats have recognized women more broadly as a key element of their coalition. The Democratic platform has continuously paid proportionally more attention to women’s issues such as abortion rights and family leave than the GOP platform. Despite GOP efforts, in every presidential election since 1980, almost every demographic group of women (cut by race, education, age, etc.) has voted more Democratic than their male counterparts.

Notably, the two Democratic presidential candidates to win the White House since the emergence of the gender gap—Bill Clinton and Barack Obama—recognized the vital role women’s support played in their elections in the first bills they signed into law: respectively, the Family and Medical Leave Act and the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act. That these were both bills specifically addressing women’s economic interests is unlikely to be an accident. Women drive Democratic victories, and women’s economic experiences drive their votes.

If Joe Biden manages to win in November, it is likely to be with the largest gender gap ever recorded. The question that should be on voters’ minds is what legislation women want him to act on first.

Historians’ perspectives on how the past informs the present

Suzanne Kahn is the director of Education, Jobs, and Worker Power and the Great Democracy Initiative at the Roosevelt Institute