Zoning (yes, zoning) could save Calgary's finances

What gets put where is one fundamental role of a well-run city and an often boring topic that can nonetheless have significant impacts on the ability of a metropolis to thrive and adapt.

Calgary follows the rigid North American model of planning that zones developments into certain areas. This provides some measure of predictability to city building, but potentially limits creative approaches that could help, for instance, a downtown core thrive even in the midst of an oil crash.

It's just one the issues that will have to be tackled by a new Calgary city council after the election on Oct. 16.

"Things tend to be dispatched in different pockets: so here is where the houses go, here is where the schools go, and then industrial zone is somewhere else and then people tend to commute and connect to these places," says Sasha Tsenkova, a professor of urban design at the University of Calgary.

"So while this is a convenient development model and a more predictable one, it's not really conducive to the dynamics of a city. In fact, for centuries, the city was not planned and built like that. Cities are about mixing things and mixing people and just that kind of messy activity that takes place."

Tsenkova acknowledges there is a place for such rigidity of use — no one wants a chemical factory next door — but the rigidity can interfere with a city and a community growing and adapting, in some cases over the course of thousands of years.

Innovation and certainty

The tension between innovation and certainty is an important one for Calgary at this point in time, as it struggles to find its feet after a solid right hook from global oil prices. Empty office towers are a central concern, but so is keeping businesses afloat and attracting new industries to a town heavily dependent on liquefied fossils.

"It can be quite an attractive incentive," said Todd Poole, president of 4Ward Planning in the U.S. who regularly speaks on the effect of planning on the economy.

"For example, let's say in buildings that are currently zoned for a particular use and don't permit for, let's say, taking a space and cutting it up for small businesses or creating live/work conditions so that you have people who want to operate small business inside of their domicile. If that's not permitted now, that's an opportunity cost. Zoning can help drive that and it doesn't cost a lot of money, certainly, for the local government to change that zoning."

It's something Calgary is trying in the downtown, relaxing rules around businesses setting up shop in the core in the hopes of eliminating empty storefronts and allowing business owners to transform their spaces, or change their use with minimal bureaucratic meddling.

There's been talk of allowing office towers to be converted to residential, something that could bring more life to a core focused on daytime business.

"It's not so much the land-use designation, it's really the fact that a lot of the investment and a lot of the jobs are related to a particular sector of the economy," says Tsenkova.

"I think the question of Calgary's downtown is perhaps the most important issue for the city."

Zoning is fine, market is needed

Poole said developers are looking for stability in planning — as in don't change the rules mid-course — rather than financial incentives in most cases. But he said the most important aspect of using zoning to create a city is making sure your plans have a chance of survival.

"Just because something is zoned a certain way doesn't mean the market will respond. Too often, government zones something because that's what they want, but they haven't paid attention to what does the market want to respond to?" he says.

"You've got these empty office buildings and perhaps there's probably demand for adaptive re-use of those buildings for residential. So there's a market demand that's perhaps not being met precisely because zoning is not permitting it."

Poole also said turning a faltering city around isn't just the purview of planners and good intentions. It requires things like an educated populace served by universities and colleges and medical services and industry — eds and meds, as he calls them.

Flexible structures

So while a city has to be flexible if it wants to stay afloat over the long haul, that flexibility must occur within a plan and a structure. It's a counter-intuitive balance but necessary to avoid conflict and decay.

"I think we're seeing in a lot of inner-city neighbourhoods where redevelopment is starting to happen, you really can't be trying to deal with these things from a one-off perspective," said Peter Oliver, the president of the Beltline Neighbourhoods Association.

"You need a local plan for where the community is headed and how redevelopment will be handled."

Oliver should know. His neighbourhood is unique in the city for its importance beyond those who live there.

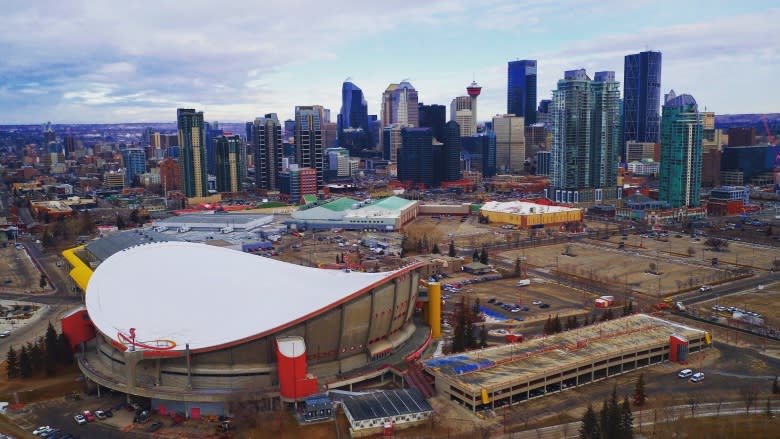

It continues to face some serious development questions and pressures. Those include a possible entertainment and culture district on its east flank that may or may not include an arena — something Oliver says his organization is watching closely.

"What we've seen from other cities, and I think what we need to be very cautious of, is a lot of these grandiose entertainment district plans actually are very bad neighbourhoods, because they don't focus on making them good neighbourhoods," he says.

"They don't focus on the residential side. It's sort of like 'we're going to have sports bars on the street because it's an arena, and it's going to be packed and busy on game nights, but outside of that, we won't worry about who will want to live there, we'll just throw up some condo towers.'"

Empty dreams

These are multi, multi million-dollar decisions that take place within the structure laid out by the city. If you can't have residential next to businesses, or allow for flexible zoning in an area that could see significant swings in demand and the economy, those millions could largely disappear. That would leave the city on the hook for a prime district near the core that sits quiet and lacks the tax inflow required to fund services and niceties.

"There's plenty of places, certainly around the United States and I imagine around Canada, where that's what they want. So they zone it that way, yet the land sits undeveloped, the office buildings sit empty, whatever it is," says Poole.

How do you encourage the growth of a successful and thriving urban district without allowing it to organically build up over decades?

The neighbourhood level

But it's not just big business and high towers affected by the land use rules set out by a city. It's also the way your neighbourhood is structured and how that changes as communities age and shift.

"When you live in a community your entire life, you forget that everyone around you is the same age and so everyone around you will also leave at the same time," said Carrie Yap, an urban planner with the Federation of Calgary Communities, which advocates for communities in planning discussions with the city.

"When they all leave, well now the elementary school is not at the capacity that it used to be. That's the hard part that people often forget."

That adaptability could mean allowing secondary suites to flourish, or laneway housing and businesses to transform the back end of our homes. It could mean allowing more pop-up businesses, or venders in city parks — something the city is considering in the Eau Claire area.

"I think the city is complicated and that we all have a role to play in city building, no matter what the scale," says Yap.

"It's not just planners, but it's community members, it's the public, we all have a role to play, whether it's going out and meeting one another, the social part is just as important as the physical part of a city."