Science and Weather

Science and WeatherFreak weather-driven tsunamis could strike the Great Lakes

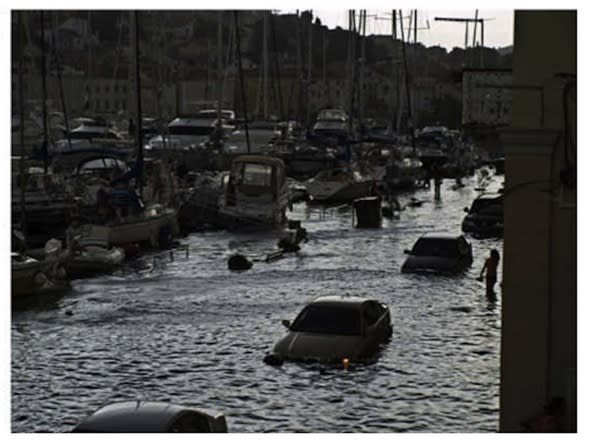

There have been some terrifying reports of tsunamis in the news over the years, but have you heard of the three-metre-tall tsunami that killed seven people in Chicago, back in June of 1954? How about the one that happened just this year, on May 27th, when the waters of Lake Erie receded from beaches around Cleveland, Ohio, and then crashed ashore as a two-metre-tall wave, knocking people off their feet and damaging several boats in the harbour? These are just two cases, discussed at last week's American Geophysical Union (AGU) Fall Meeting, of a little-known phenomenon called a meteorological tsunami, or meteotsunami.

Unlike a typical tsunami, like ones that caused wide-scale destruction around the Indian Ocean in 2004 and on the Pacific Coast of Japan in 2011, a meteotsunami isn't caused by the movement of earth, but instead by the movement of air. An intense pulse of pressure from a strong storm or squall (or even larger-scale 'gravity waves') acts like a 'thump' to the surface of the water, setting off a wave. The wave is fed more energy as this pressure pulse travels along with it at the same speed, and if that wave encounters an enclosed harbour or bay, or a shallow shoreline, it can surge up into a towering tsunami with incredible destructive potential.

[ Related: Deadly Caribbean tsunami risk overlooked ]

Meteotsunamis have one aspect that, potentially, makes them even more dangerous than typical tsunamis. For a tsunami caused by an earthquake or undersea landslide, the cause acts as an early warning of the danger, and then sophisticated early warning systems are capable of alerting people before the tsunami makes it to shore. However, because meteotsunamis can be associated with storms hundreds of kilometres away, and it is not always clear that the conditions are right for them to form, there is often no warning of their arrival.

"You have the source hundreds of kilometers away, you have no geological indication of shaking, but suddenly you can get a big wave coming in, so [meteotsunamis] are quite dangerous from that point of view," said marine geologist David Tappin, from the British Geological Survey, according to OurAmazingPlanet. Tappin presented a study at the AGU meeting of a June 2011 meteotsunami, which was spawned by a storm in the English Channel and struck without warning on the Cornish coastline.

"It's the first time a meteotsunami has been identified in England," Tappin said.

Efforts are now being made to put together a better early warning system for meteotsunamis, but it won't be easy.

[ Related: L andslide-driven megatsunamis threaten Hawaii ]

"When you have an earthquake, the earthquake just stops, so you get information on the wave before it reaches a hot spot," said Sebastian Monserrat, a physical oceanographer at the University of the Balearic Islands in Spain, who took part in two meteotsunami studies presented at the AGU meeting.

"But the atmosphere forcing is modifying what is happening in the water, and the atmospheric perturbation can change, so it is more challenging to predict a meteotsunami and to have an early warning." he added.