100 years in the making: Inside Washington's museum of African-American history

On Washington's National Mall, the dark bronze edifice stands in stark contrast to its white-marble neighbours.

Appropriately so, given the distinct story that the new National Museum of African American History and Culture, opening Saturday, seeks to tell about what it means to be American.

The Smithsonian Institution's latest addition on the plot of D.C. parkland known as "America's Front Yard" comes at a time "when social and political discourse remind us that racism is not, unfortunately, a thing of the past," Smithsonian secretary David Skorton said at a preview ceremony.

Nearly 37,000 artifacts comprise the new museum's collection, though just 3,000 are immediately available for viewing.

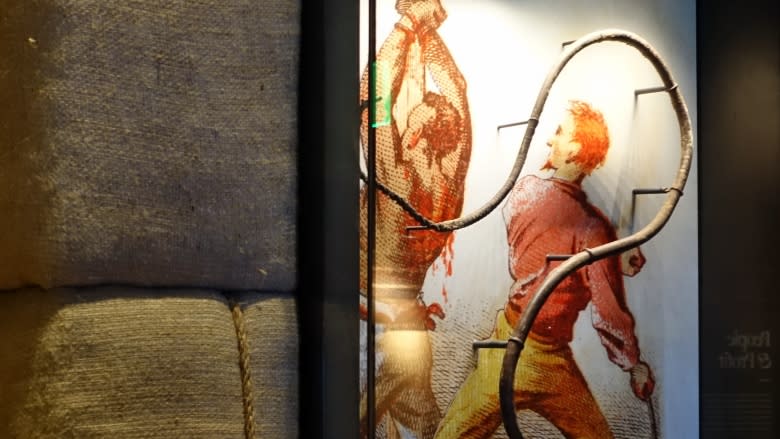

Some pieces — Olympic track legend Jesse Owens' running shoes, abolitionist Harriet Tubman's lace shawl and hymnal book or Louis Armstrong's trumpet — might summon feelings of pride and admiration.

Other artifacts, like a slave whip and wrought-iron shackles small enough for children, or the glass-topped coffin of Emmett Till, "may make you angry, or move you to tears," Skorton said, referencing the 14-year-old Mississippi teen who was murdered in 1955 after allegedly flirting with a white woman.

"Great Negro Mart," reads one undated advertisement card for a slave dealer from Memphis, Tenn. There is an 1835 bill of sale for a 16-year-old enslaved girl named Polly for $600.

Another display holds an assortment of U.S. President Barack Obama's "Hope" campaign buttons, as well as the Tracy Reese dress that Michelle Obama wore for the 50th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington.

As visitors explore its more than 37,000 square metres, the museum's founding director Lonnie Bunch wants people to think about being inside a place "that looks back, that revels in the past, but that is pointed to the future."

Rather than to build a $540-million monument to slavery and suffering, Bunch aimed for the 12 inaugural exhibitions to find a tension between the tragedy and resiliency of black Americans.

Bridging between the past, present and future has been a focus of the layout. The story proceeds chronologically.

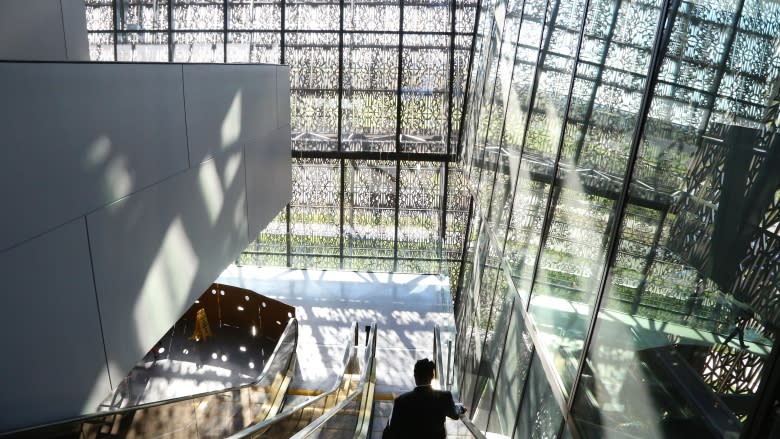

The history galleries are purposefully dark and confined. About 60 per cent of the museum is underground, evoking oppressive times. Later, visitors ascend to brighter galleries. Tape loops of speeches by civil-rights luminaries like Stokely Carmichael and Martin Luther King, Jr. transition to the funky slap bass of Sly & the Family Stone's Everyday People.

But the experience begins in the below-ground concourses with the 15th-century history of the transatlantic slave trade and the Middle Passage journey of kidnapped Africans. Ceilings are low and lighting dim, "as if you're in the ship," explained Ruthann Uithol, one of the registrars overseeing acquisition logistics.

"Those are pieces from an actual slave-wreck excavated off the coast of Cape Town," she said, pointing to a wooden ballast from 1794 Portuguese slave ship the Sao Jose Paquete de Africa.

A 17th-century quote on the wall describes conditions below the deck: "There is no Spaniard who dares to stick his head in the hatch without becoming ill … so real is the stench, the crowding and the misery."

The gallery moves through the Civil War, past the Memphis auction card selling human beings, and past the cramped Point of Pines Cabin that was rebuilt piece by piece inside the museum and which would have housed up to 16 people at a time. It moves to the segregation era from 1876 to 1968, and includes a segregated Southern Railway car that visitors can roam.

In the "Changing America" section is a vinyl recording of Malcolm X's "Ballots or Bullets" speech and a flyer for a Black Panther Party seminar on civic community programs. Aretha Franklin's R&B staple Respect pipes through speakers.

The shift represents the transitional period of the 1960s for black empowerment, said curator William Pretzer.

"It's an era in which there is a new tone to black liberation. Having achieved the Voting Rights Act and the Civil Rights Act; having crushed legal Jim Crow segregation; the question is how much more does freedom in the United States mean?"

The uglier past is never far.

The museum is connected by ramps from one level to the next, "so you move through slavery and you go into the segregation era, but you can still look down and see that slave cabin down below," Uithol said.

Higher up, natural light from the windows begins to flood in.

"So the oppression lifts as you go up, and as the story changes as you get more into the cultural galleries."

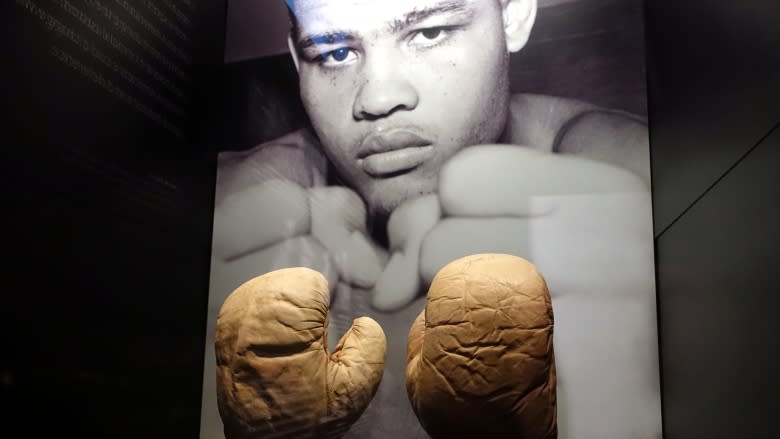

Escalators on the ground level lead to exhibits celebrating black athletes and including Muhammad Ali's boxing robe and the racket belonging to Althea Gibson, the first black woman to win a Grand Slam tennis event. The fourth floor features Chuck Berry's red Cadillac, Michael Jackson's Victory Tour fedora and a 1987 Public Enemy boom box.

From the outside, the building, wrapped in intricate metalwork and designed to resemble a West African corona, marks an assertive presence in the middle of the National Mall, with the Washington Monument to the south.

The 19th Smithsonian museum was the first to be built without a pre-existing collection, with all of its items relying on donors.

David Adjaye, the British-Ghanaian lead designer for the museum, found architectural inspiration from Yoruba tribal shrines in West Africa for the building's triumphant silhouette.

"It's a gesture going into the air, the V-shape pointing towards the sky, which is very uplifting to us as human beings," he said.

Bunch, the museum director, spoke during a press preview about the journey it took for the space to become a reality, born out of a proposal in 1915 for a monument to black Civil War veterans.

While there was congressional approval over the decades, funding for a museum dedicated to black Americans fell through, or legislation was blocked. Hope was revived in 2003, after President George W. Bush signed legislation to establish the museum and when Bunch was named founding director two years later.

"Eleven years ago, we really did start this as a staff of two," Bunch said. "All we knew was that we had a vision — a vision that we wanted all who encountered the museum to remember … the rich history of the African-American."

The museum's dedication ceremony by Obama on Saturday promises to be a particularly meaningful send-off for the first black president of the United States.

Museum attendance is expected to smash Smithsonian records, with 100,000 people already signed on as members. Organizers are issuing timed entry passes, which are free, but they won't be made available until November. Weekend tickets are gone through December.