At 13, she escaped Nazi Germany and came to Fort Worth. But the rest of her family ...

Our Uniquely Fort Worth stories celebrate what we love most about Cowtown, its history & culture. Story suggestion? Editors@star-telegram.com.

Erika Meyer, a teenage Holocaust refugee who spent three years with a foster family in Fort Worth, left a legacy of letters, brittle with age, which have lately drawn interest from a Rhineland historian, a British biographer, and an Austrian screen writer.

Erika (1925-2013), who arrived at Fort Worth’s Texas & Pacific train station June 27, 1938, with her hair in pigtails, quickly integrated into the social swing at McLean Junior and Paschal Senior High schools. She cut off her braids and enjoyed swimming, cycling and especially her new extended family.

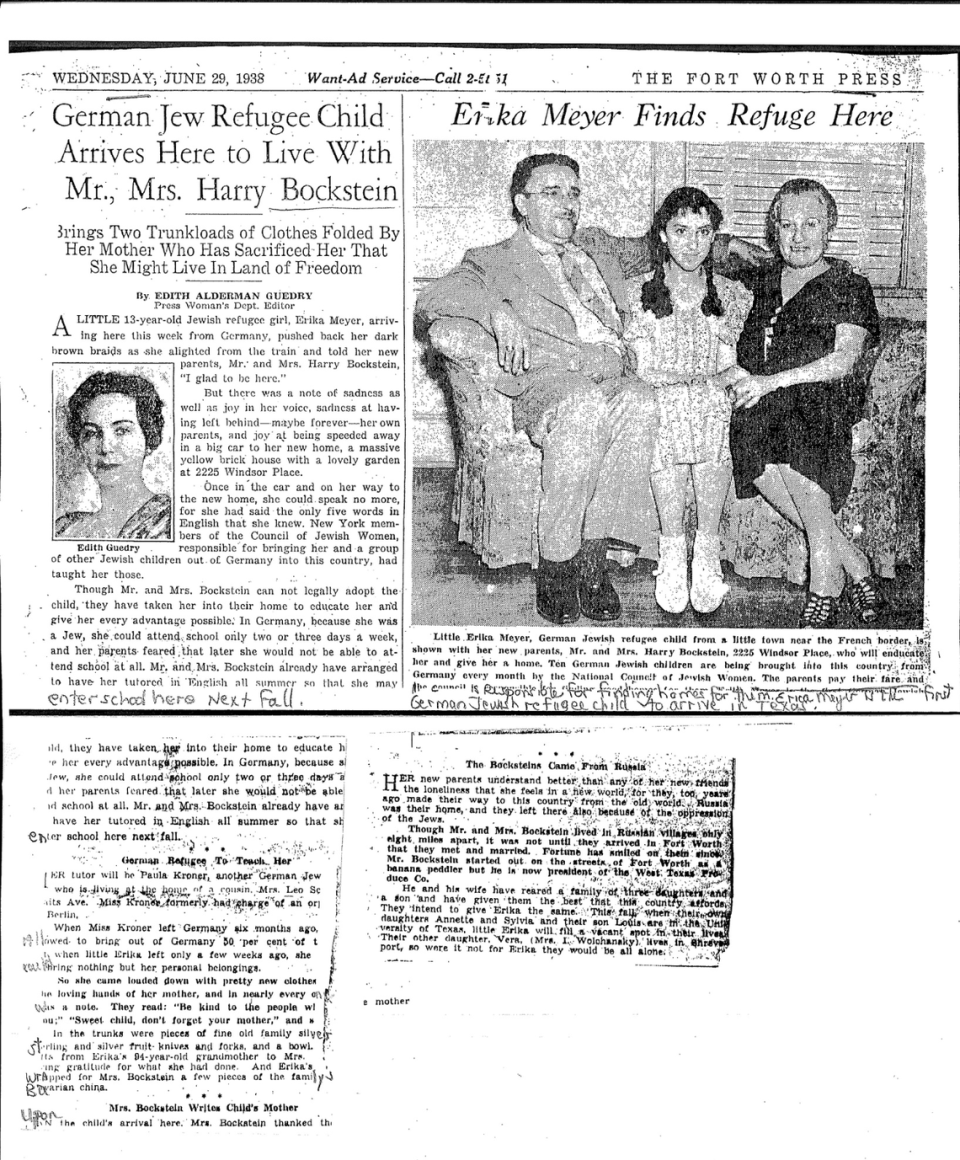

The week she arrived, local newspapers reported that she spoke but two sentences in English: “I glad to be here,” and “No go back, ever.” An article in the Fort Worth Press included a photo of Erika with her local hosts, Harry and Lena Bockstein, themselves immigrants from Czarist Russia when they were young.

Harry Bockstein had begun life in Fort Worth peddling limes. By the time he welcomed Erika into his home, he had four grown children and was president of West Texas Produce Co., a business with 150 employees. His sociable wife, Lena, a committed Zionist, was once crowned local Hadassah Queen.

The Bockstein family had applied in 1937, through German Jewish Children’s Aid and the National Council of Jewish Women, to house a child who would be among the lucky refugees to depart Nazi Germany on a Kindertransport. Plans were optimistically announced to place 10 refugees a month in private homes. But red tape in the German Reich and obstinate bureaucrats at the State Department created one delay after another.

The Bocksteins, who had selected Erika from among photos of several children, had given up hope when word arrived on June 24, 1938, that the girl would arrive by train in three days.

To teach her fluent English, they arranged for tutoring from another German immigrant, Paula Kroner, 35, a cousin of Dr. Edwin Schwarz, the city’s first pediatrician. The tutor had fled Germany in January 1938, when Jews were allowed to leave with half their savings. By the time Erika departed in June, Jews in flight could no longer bring currency, only personal belongings. Erika’s mother had lovingly filled two trunks with clothing, placing handwritten notes to her daughter between dresses and sweaters along with antique silver and Bavarian china as presents for the Bocksteins.

Letters show impact of Nazism

Erika’s mother, father, 5-year-old sister Helga, grandmother and other relatives mailed several letters a week to the Bocksteins’ two-story yellow-brick home on Windsor Place. Those letters, handwritten between 1938 and 1941 on several hundred sheets of paper, were donated in 2021 to New York’s Leo Baeck Institute for the Study of German-Jewish History and Culture. The letters’ contents — at times personal, poignant and painful — are slowly being translated into English from Sutterlin, an old-fashioned German handwriting style. The contents reveal how the rise of Nazism impacted Erika’s family in Langenfeld, a Rhineland village between Dusseldorf and Cologne.

The name of the street where her family lived changed from Hauptstrasse to Adolf Hitler Strasse, according to German historian Gunter Schmitz, who has studied the fate of the region’s Jews. On Kristallnacht, Nov. 10, 1938, Storm Troopers destroyed Meyer Brothers, the clothing and furniture store that Erika’s father and uncle operated.

Later letters reflect her parents’ desperate efforts to join Erika in the United States. To immigrate, the family needed diplomatic connections, letters to refugee agencies and financial sponsors. The Bocksteins likely tried to help.

As Erika grasped how trapped her family was in wartime Germany, she moved to Brooklyn at the end of 1941 and transferred from Paschal to James Madison High. Perhaps from New York the teen thought she could lobby immigration officials for her family’s entry to the U.S. While waiting tables at Woolworths, she met Norman Aronstam, a salesman. The couple married on Valentine’s eve in 1944 and spent their one-night honeymoon at Manhattan’s landmark Essex Hotel, according to the New York Times.

Well into the 1950s, Erika held out hope that her relatives had survived the Holocaust and somehow made their way to New York. Her son Elliot Aronstam, a retired Broadway accountant, says in a recorded online exhibit of the Leo Baeck Institute: “I remember my father going downstairs from our apartment and just walking around the area ... because my mother is saying ... I know that they’re here. I know that they’re out there. We have to go find them.”

Ultimately, it was verified that Erika’s parents and little sister had been deported from Dusseldorf Dec. 11, 1941. Her father perished at a ghetto in Riga, Latvia. Her mother and sister were murdered at Stutthof, a notorious death camp in Poland.

Biography on Erika Meyer

“It is so important to keep alive stories like these,” said British writer Ariana Neumann, who is writing a biography that focuses on Erika’s life from 1936 to 1945. Neumann’s recent book, “When Time Stopped: A Memoir of My Father’s War and What Remains,” won the Dayton Literary Peace prize in 2021 and a 2020 National Jewish Book Award.

Austrian screen writer Manfred Corrine is working with Gunter Schmitz, the Rhineland historian, on a documentary about Erika’s cousin, Edith Meyer. Edith and her non-Jewish fiancé were arrested trying to cross the border to Switzerland. She perished in Auschwitz. He was shot trying to escape.

Erika Meyer’s legacy continues. In Cowtown, Naomi Rosenfield, former director of the Jewish Federation of Fort Worth and Tarrant County, recalled that in the 1990s, when the local community resettled dozens of Soviet Jews, the Bocksteins’ son-in-law, Sol Taylor, quietly underwrote many of the costs, including funerals for elderly Russian immigrants.

What motivated Taylor were the warm experiences his wife’s family had when they shared their home and good fortune with a teenager named Erika Meyer.

Hollace Ava Weiner, an archivist, author, and historian, is director of the Fort Worth Jewish Archives.