At 14 he slaughtered the woman who raised him and at 21, he walked free. What now?

By all accounts, Donovan Nicholas wasn't acting like himself when he repeatedly stabbed and then shot the woman he called "Mom" late one afternoon in April 2017.

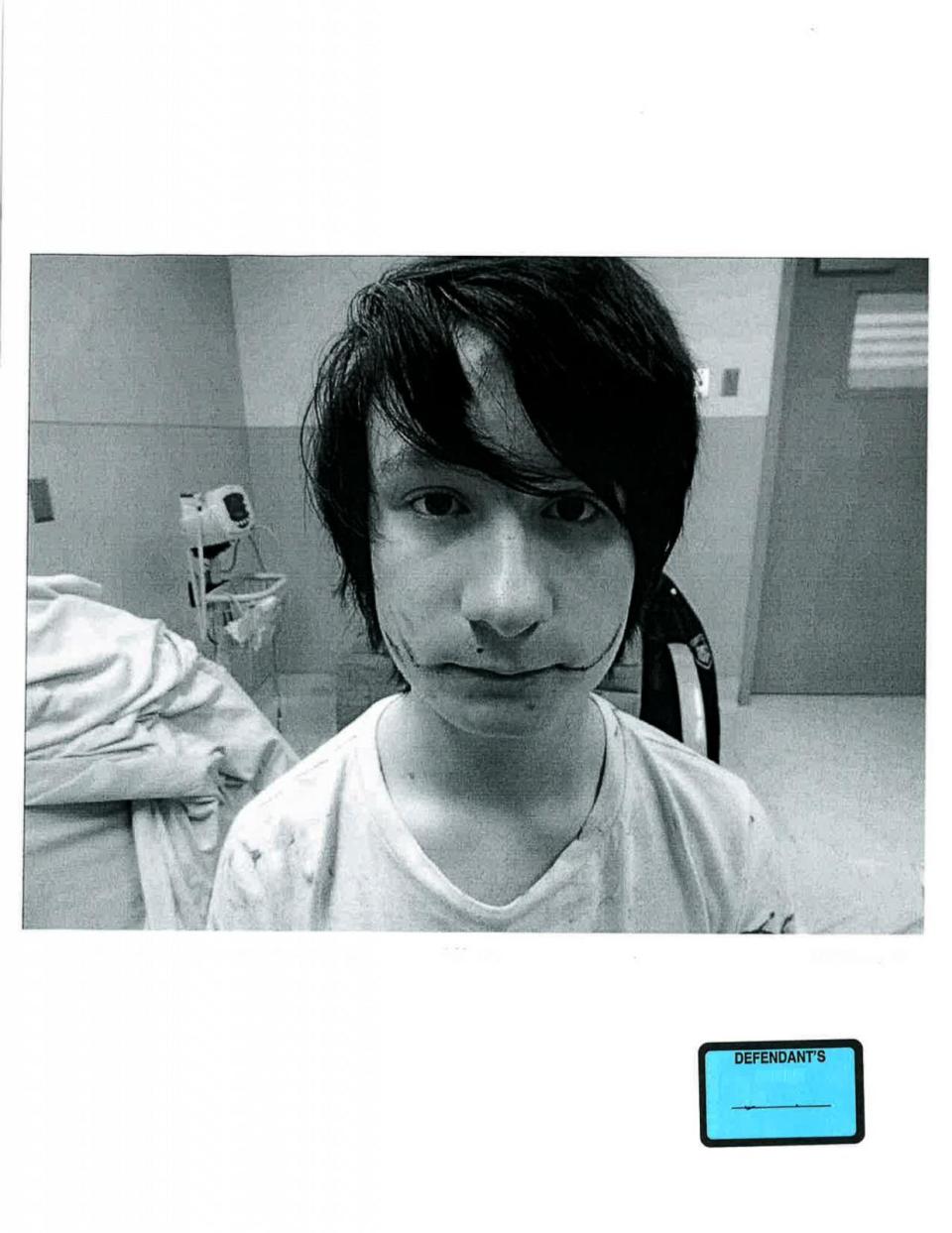

Shaggy-haired and thin, Donovan, a few months shy of his 15th birthday, was dressed specially for the occasion, he later said. He wore black pants and a white T-shirt. A small blade had been used in an amateurish attempt to carve his mouth into a giant, gash-like grin. His hand held a kitchen knife. His body hid beneath the front staircase of his family's two-story farmhouse in Urbana, Ohio, and his father's longtime girlfriend, 40-year-old Heidi Fay Taylor was lured downstairs to die.

Not long after, exhausted and drenched in blood, Donovan called 911 from the family's kitchen.

"I swear it wasn't me," he told the dispatcher, voice stuttering. "It was Jeff. Jeff is inside me."

Until then, he had only ever told two other people about "Jeff," meaning "Jeff the Killer" -- the alternate personality that he admired and then became consumed by, modeled after a popular horror character on the internet, he subsequently explained while in custody.

Jeff first appeared in online stories and artwork more than 10 years ago and is sometimes depicted as an eyelid-less maniac, badly wounded after standing up to a group of bullies, with a permanent grimace on his pale face. He wears a white shirt and black pants. He kills with a knife.

"I am so scared," Donovan said on the 911 call. "I didn't want to kill her. I hate Jeff so much. He's going to make me die in prison."

"I swear it wasn't my fault," he said.

No one who spoke with ABC News for this story said they had ever seen anything quite like it. As one judge later wrote, the case raised "disturbing questions" about a juvenile justice system "that cannot or will not" adequately respond to kids who kill.

"There's no question that this case was a tragedy all around," Tim Hackett, an attorney who helped lead Donovan's appeal, told ABC News.

It's also a case, Hackett argued, that "demonstrates a need for compassion, as hard as that might be."

Donovan's attorneys described him to ABC News as "very troubled and desperate" and "severely mentally ill" at the time of the murder, but prosecutors have consistently challenged his account of having an alternate personality.

In interviews, they've instead cast him as a sullen teenager twisted by homicidal fantasies and enamored with an out-of-state girlfriend, whose rage was seemingly sparked by a simple act of discipline: He didn't want Taylor to take his cell phone away because he'd been exchanging inappropriate messages with the girl.

Fourteen is the youngest age someone in Ohio can be moved to adult court and Donovan was one of the youngest children prosecuted as an adult in the state in the last decade, records show.

However, over the course of a long legal battle that ended before the state Supreme Court, Donovan's attorneys and advocates said the system had ignored evidence that he could be helped with the right psychiatric care, undermining one of the central promises of the state's juvenile court system.

"We're all more than the worst thing that we've ever done, and that holds true for kids who do terrible things," Kim Jordan, a law professor at Ohio State University and director of the Justice for Children Project, who joined a brief filed with the state Supreme Court supporting Donovan, told ABC News.

"I think not every kid is going to be a success story," Jordan said. "But they deserve the opportunity."

In a narrow 4-3 decision last winter, the high court agreed, leading to Donovan being released on his 21st birthday this summer.

Now he and everyone around him have to figure out what to do next.

The ruling caught Taylor's loved ones by surprise. Her other children say the memory of her murder, scabbed over with time, felt raw again.

"You think everything's going right, you think you're going to get justice for your family and your mom, and then guess who gets to walk away?" Todd Taylor, Heidi Taylor's son, told ABC News earlier this year.

"It just reopens all that and brings back some of that PTSD," Heidi Taylor's daughter, Alyssa Nicholas, said in an interview in April as she awaited Donovan's release from prison.

"The system has just failed in this entire situation," she said.

On that, she and Donovan's attorneys agree.

Hackett said that "there are many stories within this case." This report -- based on two dozen interviews and a review of more than 2,000 pages of documents -- details some of them.

There is the story of Donovan Asher Nicholas, a boy growing up in the farm country of Champaign County, Ohio. He might have been called precocious (his dad said that by age 3, he was talking like he was 5) except that, as he got older, he found his self-esteem gnawed away by feelings of worthlessness, loneliness and despair, he told a court psychologist while in custody.

He "reported feeling isolated and separated from those around him for several years," Daniel Hrinko, one of three doctors who evaluated Donovan after his arrest, wrote for the court.

Donovan began struggling with suicidal thoughts around sixth grade, according to his attorneys. That's also when he began cutting himself, he said, according to one of Hrinko's evaluations, which was reviewed by ABC News.

Hrinko said Donovan told him that he'd hoped there would be some catharsis once Heidi Taylor and his dad, Shane Nicholas, learned how he was harming himself.

"I would've been happy if they would've said, 'You are worth something and we care.' Nope, they just yelled," Donovan told the doctor.

Hrinko wrote that everyone around Donovan "left it up to [him] to decide if he would seek mental health treatment." According to one of Donovan's appellate filings, "He predictably didn't."

He was very smart, his family agreed, and usually quiet. He liked to fish, his dad said at his trial -- but he hated the act of catching them, worried that they'd suffocate in the time that they were out of the water. He liked to dress in black, even dyeing his hair to match, according to Hrinko's evaluation.

He listened to heavy metal music and the soothing sounds of classical but dismissed country songs -- "all about beer and tractors," he told Hrinko in one of two 2017 sessions with the psychologist.

"Different is better than normal," he said then.

By 14, Donovan was thinking about how to kill others, according to evidence presented at his trial -- trading numerous texts with a school friend who shared his fixation with the macabre.

For a boy his age, "he presented well to the Court with a level of maturity that belies the circumstances of this matter," the juvenile judge in his case once wrote.

But he kept a lot hidden, too, telling "virtually no one about what was happening in his life or the thoughts he was having," Hrinko wrote in his evaluation.

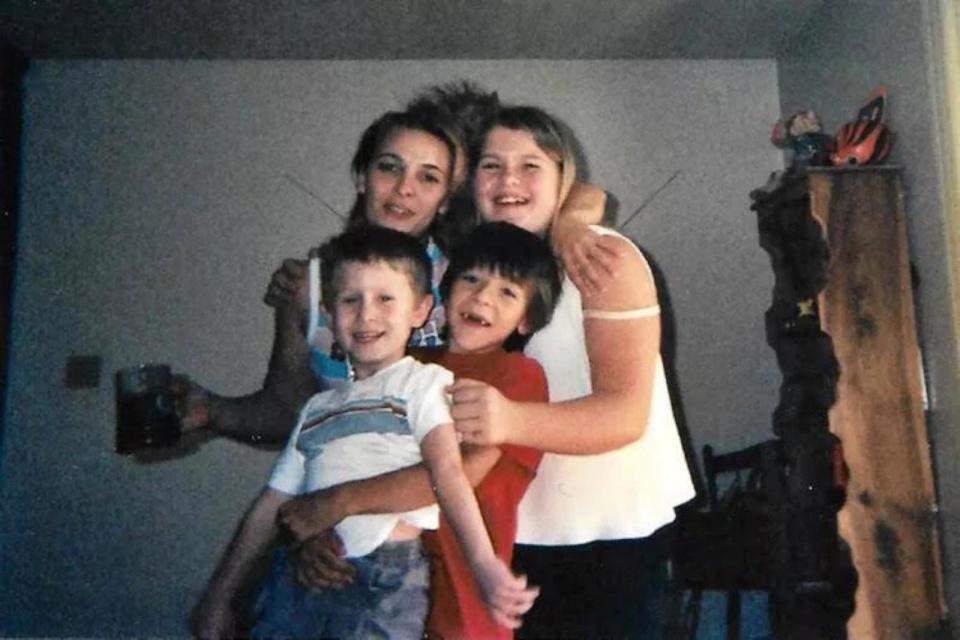

Then there is the story of the woman who was raising Donovan, Heidi Fay Taylor, who had two kids of her own and who built a blended family with Donovan's dad.

Heidi Taylor and Donovan's relationship was "complex," his attorneys wrote.

"I believe the main tension would be that she was not his real mother. And his real mother was not part of his life. That, he took really hard," Shane Nicholas, who declined to comment for this story, said at Donovan's trial.

Donovan "never vented to me," his father said. "He always used her as his outlet to vent. Whether good or bad."

As the youngest child, Donovan was the only one still living at home at the time of the murder. Shane Nicholas traveled extensively for work; often, it was only Donovan and Heidi Taylor together.

"She said, I quote, that I was a 'waste of space.' Other things like that," Donovan testified of Heidi Taylor at a pretrial hearing.

"She would yell and scream at me for things that I've done but also things that I haven't done," he said at the hearing. "She did not treat me fairly," he said.

Because Donovan killed Heidi Taylor, his version of their life -- describing her as emotionally neglectful, overly strict and dismissive, even cruel -- is the dominant account described in the court battle. She can't speak for herself.

That's something Heidi Taylor's family and friends, who remember her as an open heart, can't stand.

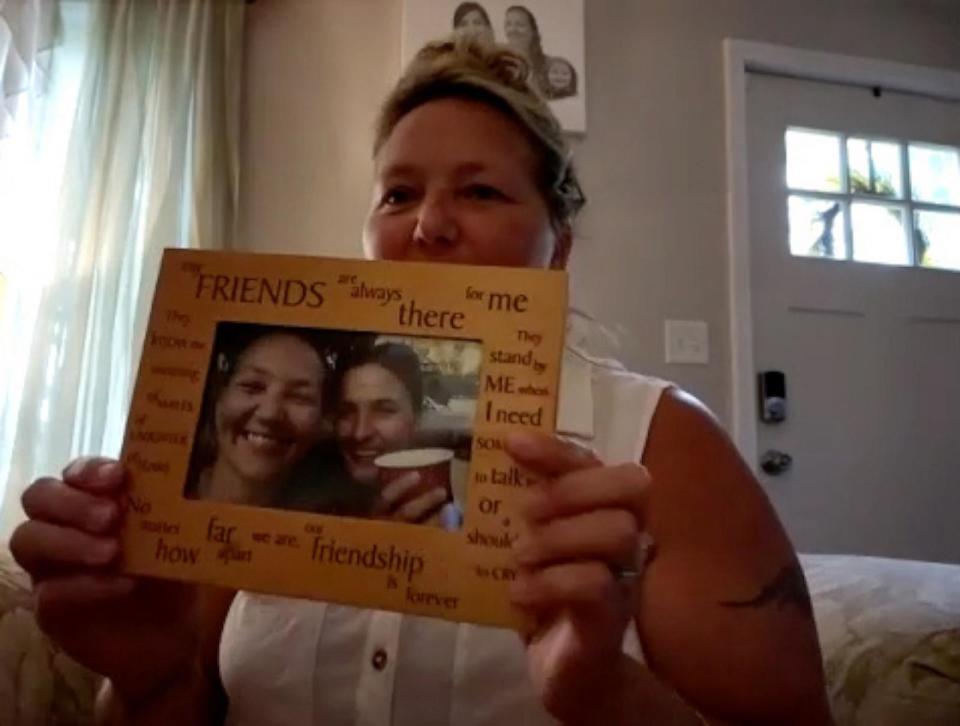

"She had such a strong personality, but she was so funny," her best friend, Angie Cooper, told ABC News. "Oh my god, I miss her voice."

"It was easy to open up to her ... and she was just so personable," Cooper said, going on to add, "She was like coming home."

Yes, Heidi Taylor could be somewhat "rough" on Donovan, Todd Taylor, her son, said. "Not any worse than any other parent. I feel like she was rough on him because she knew he had potential to go far in life."

"She loved him," Cooper said.

Heidi Taylor was a petite woman -- "no bigger than a minute," Cooper said -- who loved sweet tea and the draping branches of willow trees and the beach. She cooked as an act of affection: special meals for the holidays, for birthdays. She was always losing things. Once, her keys ended up in a bag in the freezer for two days.

She helped raise three children and was helping raise two grandchildren, with another on the way. "There was nothing she loved more," Alyssa Nicholas said.

And then there is the story of the system that had to make sense of all of this: how much Donovan was truly to blame and what should be done with him as a result.

"There was a child who needed help, who needed care," said Hackett, his lawyer. "And rather than asking or deciding whether he would be amenable to the system, at some point folks started wondering whether the system would be amenable to him.

"And I think that's always been the wrong question."

Todd Taylor has looked back at what happened to his mom -- at what he's sure Donovan did -- and come to another conclusion: "I feel like he played the entire system from the get-go."

Donovan, through his attorneys, declined ABC News' request to be interviewed.

What Donovan did

Only about 2,300 children have been tried as adults in Ohio since 2011 and nearly all of them were 16 years or older, a review of state data shows.

In rural Champaign County, Donovan was even more of an outlier. Kevin Talebi, the prosecutor there, said Donovan was the youngest person he'd ever sought to try in adult court.

"This is a very unique situation," Talebi told ABC News. Not just because of Donovan's youth but also his attempt to plead insanity, the details of his mental state and the "extraordinarily gruesome attack" that ended Heidi Taylor's life, Talebi said.

A medical examiner determined Heidi Taylor, standing 5-foot-1 and weighing 114 pounds, had been stabbed at least 62 times -- on her hands, her arms, her throat, her face, her skull, the injuries ranging in their size and severity.

And then she was shot, once, in the forehead.

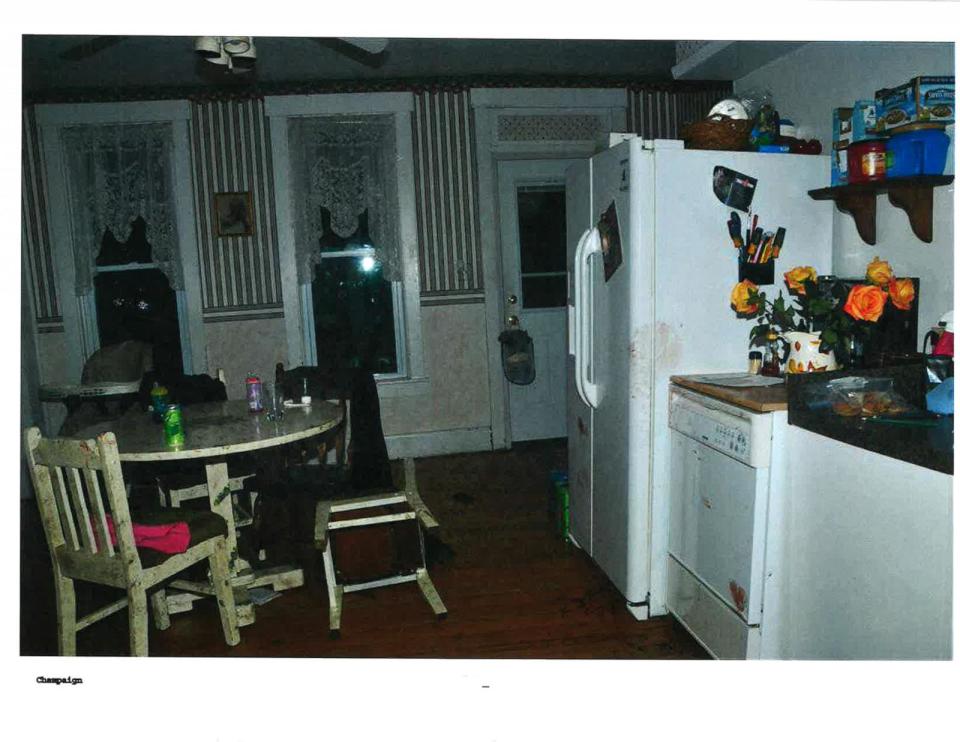

Court documents and trial testimony show how her murder left a chaotic trail in the home: smears and splatters of blood along the floor and walls as Heidi fought for her life from room to room as Donovan, just two inches taller and a few pounds heavier, pursued her. Donovan admitted in court that at one point, when he and Heidi made it to the kitchen and before she fled to her bedroom in a final attempt to get help, there was a pause: As she lay on the floor, he got himself a glass of water.

After the murder, investigators testified that they found some of Heidi's press-on fingernails, apparently lost in the struggle, and the wood-handled knife discarded on the dining room table.

There has never been a dispute about who was physically responsible for all of that violence. It was Donovan: his hands wielded the knife, his fingers loaded the gun.

The fight was about mental health and potential rehabilitation.

Donovan's lawyers argued he should remain in juvenile court, which would have sought ways to treat his underlying problems until he turned 21.

Talebi pushed to have Donovan tried as an adult. "From my perspective, seven years [in the juvenile system] is not enough. And so the only way we could adequately protect society and address this defendant would be through the adult system," he said.

The juvenile judge, Lori Reisinger, agreed.

Crucially and controversially, Reisinger set aside testimony from a state youth services official that sufficient mental health resources would be available to Donovan, which aligned with the view of Hrinko, the psychologist who found that he could "effectively be treated" as a juvenile.

Once the system started treating Donovan like an adult, he sought to plead not guilty by reason of insanity.

The three psychologists who assessed him after the murder did not all agree on his diagnosis. According to their findings, as described in legal filings, two of them said he had a serious mental illness but differed on what kind. The third found no severe mental disorder.

One of the doctors, Benjamin Hendrickson, diagnosed him with depressive disorder. Hrinko determined Donovan had four of five key symptoms consistent with dissociative identity disorder (DID), though -- unlike with other DID patients -- he said he remained aware in the episodes when his alternate personality took over.

A third psychologist, Kara Marciani, found "that [Donovan] did not suffer from symptoms of a magnitude that would constitute a serious or chronic mental illness," according to one of Donovan's appellate filings.

Hrinko acknowledged in one of his evaluations that there was the possibility Donovan had concocted "Jeff" but was inclined against it, given evidence like text messages and journal entries that showed Donovan acting differently, as though someone else was in control.

Donovan testified that he first found out about Jeff through a horror website where users trade their own tales. "I fell in love with the story because Jeff the Killer was who I wanted to be," he said. "Minus the killing."

As he told Hrinko: "I never had power. Jeff has power."

In Donovan's telling, what started as a fascination then turned into a friend and then into something more frightening.

"It was like cell division," he told Hrinko in 2017. "I grew into two people slowly. Soon the bad side was talking to me."

Later, testifying at the pretrial hearing, Donovan said he had enjoyed the sensation of another voice in his head: "I thought it was pretty cool to have someone to talk to that I admired all day."

But, he said, "My bad side started getting bigger and worse. I would think about the options and was often torn [between them] but generally picked the good side."

DID, previously known as multiple personality disorder, is fairly rare: Studies indicate it occurs in up to 1% of the population, according to Stanford University's Dr. David Spiegel, who led the group that first crafted the criteria to diagnose it.

Like anyone else, DID patients are capable of violence, Emory University's Dr. J. Douglas Bremner, who has extensively studied trauma, the brain and dissociation, told ABC News. But DID itself doesn't determine that, he said.

Spiegel agreed: "As a group, and just like most psychiatric patients, they're more likely to be harmed than harm other people."

People with DID "can get a lot better," Spiegel said. He and Bremner said that typical treatments include extensive therapy, sometimes with supplementary medication like anti-depressants.

"It's not quick and it's not easy," Spiegel said.

The differences of opinion on Donovan should not be used to ignore the psychologists' broader consensus that he was unwell, Hrinko, his first evaluator, wrote to the court: All three doctors found "disturbances of behavior, aberrant experiences of thought and mood, and behaviors that often included as symptoms of numerous psychiatric disorders."

Under Ohio law, it wasn't enough for Donovan to be seriously mentally ill -- which the adult court judge, Nick Selvaggio, found was a legitimate question for the jury. To plead insanity, Donovan also would have had to show his illness stopped him from knowing what he did was wrong. Selvaggio rejected that.

"Jeff ... fully believes that murder is 100% OK," Donovan testified at a pretrial hearing. Under cross-examination, he said Jeff "knew murder was illegal, but he did not believe that it was wrong."

Unable to plead insanity, Donovan instead testified at trial that his loss of control to Jeff was like a "very, very deep trance." Jurors convicted him anyway.

On July 24, 2018, two weeks after his 16th birthday, Donovan was sentenced to life in prison with the possibility of parole after 28 years for committing aggravated murder with a firearm.

In deciding Donovan's punishment, Selvaggio appeared to take a skeptical view of the teen, concluding that "the self-reported emergence of the alternate personality was actually created and promoted by the Defendant in order to rationalize and allocate blame for the homicidal act."

Donovan continued to appeal, contending that he should never have been treated as an adult.

In a brief to the Ohio Supreme Court, Hackett and Donovan's legal team argued the juvenile court judge was wrong, all those years ago -- an error, as Hackett told ABC News, "that set the trajectory for everything that happened since."

A majority of the justices ruled in December 2022: Donovan's lawyers were right. Reisinger had improperly ignored evidence, presented at the hearing on whether to try him as an adult, of his potential for rehabilitation if he got the care available to him.

Then-Chief Justice Maureen O'Connor wrote in the majority opinion sending the case back to juvenile court that "absent that misperception," the likelihood tipped toward the system trying to save Donovan rather than merely make him suffer.

Still, the seven justices were split on such a ruling, which largely dismissed the legal technicalities of Donovan's argument before, at last, siding with him on the point of potential rehabilitation and setting him on the path to freedom.

The three-judge minority, in their dissent, labeled that "overreach" and warned of consequences: "The majority is simply imposing a result that it wants, but it is a result that no one is, or can be, prepared for."

Donovan, for his part, "met the [Supreme Court] decision with a mixture of emotions," according to attorney Katherine Sato, who represents him alongside Hackett.

He was "certainly relieved and hopeful -- hopeful he wouldn't spend the rest of his life in prison," Sato said. "But he understands that the decision was not welcomed by everyone in his family."

It was not.

"I don't see how a person can come back from that and be a good person," Heidi's son, Todd Taylor, said. "So if he does and he gets a little piece of paper saying he's rehabilitated or however that works, as far as I'm concerned it's just stuff to start a fire. It means nothing to me."

'It's not going to be a straight line'

Once Donovan's case was sent back to juvenile court in the new year, he pleaded guilty to aggravated murder and on his 21st birthday, in July, he walked free. He is subject to almost no restrictions, except that he can't get a gun in the state.

"I feel that it is a misjustice and I'm appalled," Cooper said.

It was Todd Taylor, actually, who drove Donovan and Donovan's dad home after Donovan's dad used his car to pick Donovan up from a state youth facility.

On the ride back, Todd Taylor said, Donovan sat in the backseat with a box of his things. He didn't say a word. About 15 minutes in, Todd Taylor said he told Donovan, "I don't want to hear your name unless it's for getting 'Citizen of the Year.'"

"He told me he understood and that he understood how I felt," Todd Taylor remembered. "And ... he hopes one day that we can put this behind us. And then he started crying."

"I'm sorry," Todd Taylor said he told Donovan. "As much as I love you and as much as I care about you, it's never gonna happen."

They've talked again, more recently: Todd Taylor called to angrily vent at Donovan, though he said he knows it doesn't really do any good.

"The more I try to figure out what's going on in that kid's head, the more I go crazy," he said.

Many of the people directly involved in the case acknowledge some reluctance to talk about it publicly. It's a terrible, terrible thing, they say -- and it has already been picked over by true crime fanatics online. Podcast hosts talk about it; the details get mined for social media content. A video of Donovan's 911 call has drawn tens of thousands of views.

"It's like the thing is just haunting me," Alyssa Nicholas said. "Like you just can't get away from it now."

But theirs is not the only story to tell.

"If we just focus on the crime, then we don't do her justice," Cooper said of Heidi Taylor.

In a victim impact statement after Donovan's conviction, in 2018, Alyssa Nicholas described a version of her mom to eclipse how Donovan had described her.

"She was my biggest supporter and my best friend. She would go to extraordinary lengths to provide everything she could for our family," Alyssa Nicholas said.

The family keeps a chair empty for her at meals, Cooper said, and likes to celebrate with some of her favorite food. They pass stories around, Todd Taylor said, "and just have fun in her name."

"She was a light and I can't even -- just saying it doesn't even do it justice," Cooper said.

Talebi, like Heidi Taylor's family, feels some frustration at how long the legal battle took -- while stressing that he respects the high court's final ruling even though it "didn't give the juvenile court system any time."

"Would things have been different if he was sent to the juvenile court system at the age of 14? Unfortunately, we're not going to know," Talebi said.

He said he hopes something horrible doesn't happen again.

"The reality is, defendants, after they commit violent crime, after they serve their prison sentences, they are released back into society. And society has to deal with those individuals," Talebi said.

At his final court hearing, in June, Donovan said therapy had helped him; so did embracing God.

"I can't express how different I am today. I hope I can do what I can to ease my family's pain," he said, according to Brenda Burns, managing editor of the local Urbana Daily Citizen newspaper, who was in the room.

Donovan, who received a high school diploma behind bars, is working now and receiving further treatment, according to his lawyers. They said that confidentiality prevents them from discussing his mental health in more detail, including whether he continues to struggle with an alternate personality. His dad is supporting him.

Sato, one of his attorneys, said Donovan had no violent incidents at all during his incarceration.

"He's talked a lot about his maturity, how he thinks differently now than he did at 14," she said.

She and Hackett said they plan to continue to support Donovan in his reintegration. "We're very confident that he is on the right path," she said.

"It's not going to be without struggle," Hackett said. "It's not going to be a straight line."

In the decade since the U.S. Supreme Court narrowed the use of mandatory sentences of life in prison without parole for children who commit murder, a growing list of states has banned the punishment entirely for youth offenders. In 2021, Ohio became one of them.

"Simply throwing a child away, while it may initially feel good ... ultimately, that does not satisfy our desire for real justice, which is trying to heal and trying to make things right and trying to find a way forward," said Preston Shipp, senior policy counsel with the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth, which supported the legislation in Ohio and elsewhere.

But he recognizes that victims and their families may hold another view.

"The Donovan that I knew died the day that he murdered his mother," Cooper said.

Alyssa Nicholas has no intention of seeing Donovan again: She said she took out a protective order for her and her three girls, growing up without their Nana.

What does she think is the fair way to treat the young man she once called her brother? Asked that in one of her interviews with ABC News, she paused before she answered. She took a deep breath.

"I don't know," she said.

"If he could get treatment and public safety could be guaranteed, then, I mean, he has a life to live as well," she said. "But it definitely would not be a part of mine."

At 14 he slaughtered the woman who raised him and at 21, he walked free. What now? originally appeared on abcnews.go.com