2 B.C. councillors reflect on combined 100 years in local politics as they prepare to retire

When you've been in local government for a half-century, what does retirement look like?

"I'm just going to keep on doing what I'm doing. I just won't be on council, that's all," said Harold Steves — first elected as a councillor in Richmond, B.C., in 1968 — as he promised to continue his advocacy for farmland preservation.

Lois Jackson, first elected as a Delta, B.C., councillor in 1972, said her son recently asked her: "Mother, are you ever going to grow up?"

"I said no. I'll just be part of the local scene," said Jackson, who was mayor for 19 of her years serving the city.

Both in their mid-80s, the two longest serving municipal politicians in British Columbia decided not to seek re-election this October.

Their departure brings to mind how much their respective communities have changed in the past half-century — Delta has more than doubled in population and Richmond tripled since the pair were first elected — and how much local politics has as well.

'People didn't know how to fight city hall'

"It was very strange having a woman at the table, I'll tell you," said Jackson with a laugh, remembering being the first woman elected to Delta council 50 years ago.

She said when she started, she formed a strategy of getting her main ally on council to put forward the motions or amendments she wanted passed, knowing some of the councillors wouldn't respect her ideas.

But she also believed one of the reasons she kept getting elected was being a mother in a rapidly growing city with plenty of young families and young mothers who wanted someone on their side.

"We didn't have arenas, we didn't have playing fields … we had so many children and they needed so many things to keep them safe and happy," Jackson said.

The grandson of one of the first settlers in Richmond who lived in Steveston — the waterfront neighbourhood named for his family — Steves had no such issues gaining respect at the council table.

At the same time, his push for preserving the city's farmland and parks frequently led him into conflict with much of the city's establishment — beginning with his first campaign in 1968 as a member of the Richmond Anti-Pollution Association, which sought to stop an oil port planned for Garry Point.

"People didn't know how to fight city hall back then," he said.

"Today if you do something that people don't like, they'll organize and campaign and write petitions and attend council meetings and sometimes they'll change council's mind, and that's the role I played for the last 50 years … I think about half the parks in Richmond came due to public protest."

Focus on the environment

Steves and Jackson are different politically. He was an NDP MLA in the 1970s, while she was periodically recruited by centre-right parties and is passionate about balanced budgets.

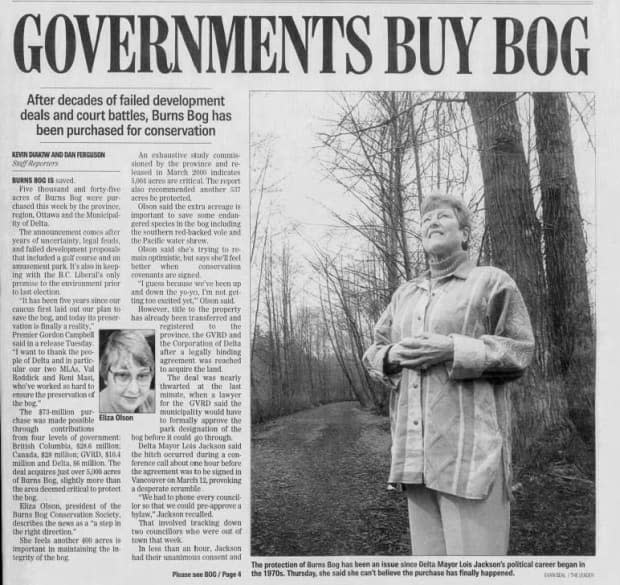

But championing agricultural land is an issue that has long united them, beginning in the early 1970s when Steves helped create the Agricultural Land Commission.

"They actually put it to the councils of the Lower Mainland: What do you want to do with your farmland? What do you want to protect?" said Jackson.

"We wanted to emphasize keeping the farms and the land as big parcels as possible, because that makes for a far better base for the farm."

For Steves, the preservation of so much of Richmond's farmland is a cause for celebration and optimism for the future, and a sign that politics has changed for the better.

"On social media you get a lot of unnamed people, trolls or whatever, that attack you … but by and large it's a good way of communicating and spreading the message," he said.

Jackson is somewhat more circumspect about the future, worried about more development ruining the environment and social media further polarizing people.

"This whole electronic age has brought a very different dynamic to everyone's life," she said.

"We have to slow down and be more contemplative, appreciate what we have, help others. Those used to be the mantras of the day many years ago. Of course, I can say this because I'm way older than all of you."

'I guess I felt I could do more at home'

Jackson and Steves are far from the only long-serving local politicians stepping down this October.

In Burnaby, councillors Dan Johnston (first elected in 1993) and Colleen Jordan (2002) are retiring, while the longest serving councillors in Victoria (Geoff Young, first elected in 1983) and Prince George (Murray Krause, 1996) are also calling it quits.

The job has become more demanding as decades have gone on, with more avenues for public input than ever before, and more areas of jurisdiction less funded by higher levels of government than in the past.

There are also more political parties than ever before, and running for council is now a four-year commitment instead of just two or three.

Despite all that, Jackson looks back at time in local politics with satisfaction — and content that she never ran for provincial or federal office.

"I guess I like the local flavour. I like the neighbourhood. I guess I felt I could do more at home," said Jackson.

"In Ottawa, it's the party you have to support. I have a problem with that. I don't like people telling me how I have to think."

It's a similar story for Steves, as he prepares for an active retirement in Steveston.

"There's so much more you can do at the local level on all the issues," he said.

"So I bought into the slogan … think globally, act locally."