7 Saint John graves that definitely aren't haunted

Ghosts aren't real. Right?

But if they were — they might haunt these seven final resting places in Canada's oldest incorporated city.

1. Halloween double murderer

In 1868, on the afternoon of Halloween, 23-year-old Sarah Margaret (Maggie) Vail and her young daughter road out on Black River Road to meet their deaths.

At Vail's side was John A. Munroe — a married, well-respected Saint John architect, a father of two, known for working on the city's finest homes and buildings.

Three years earlier, he had started a relationship with working class, unmarried, Vail. Their clandestine affair resulted in a daughter, Ella May.

It ended violently on Oct. 31, when Munroe became enraged with his lover while they rode out in rural Simonds Parish. He shot Vail in the head, strangled their child and hid their bodies in the brambles, where they lay undiscovered until the following fall.

Munroe was quickly linked to the crime and after a sensational trial was found guilty, confessing on Feb. 14, 1870, "it was the money, my anger with her at the time and my bad thoughts … [that ] caused me to do the bad act."

Munroe was hanged Feb. 15, 1870, at the Saint John Gaol on Sydney Street. While Munroe's name does not appear on the gravestone, he is buried in his family plot at Fernhill Cemetery.

Maggie Vail and Ella May were memorialized in 2013 with a monument at Old Cedar Hill Cemetery in west Saint John.

2. Death from a broken heart

The Hurwitzes were Russian Jews who immigrated to Saint John in 1907 and settled near Long Wharf.

In the spring of 1921, their 16-year old son, Harry, was seized by an attack of appendicitis and admitted to the General Public Hospital for surgery. It was not a success. He died on the evening of April 16.

After her son's death, Harry's mother, Dora Hurwitz, would come to Fernhill "early in the morning and stay here right til dark," said longtime Fernhill Cemetery worker Roy Clayton in a 1975 National Film Board interview.

It was "a case of a broken heart, if there was such a thing," Clayton said. "We put a bench right over there for her to sit on. She was a short woman, her feet wouldn't touch the ground. She would sit there and weep all day and wouldn't take no notice of anybody."

Less than a year later, Dora was also dead. The official cause was heart failure.

She and her son are immortalized together in twin enamel portraits in Shaarei Zedek Cemetery.

3. Shipwrecked, killed and dug up

This stone dates back to 1787 — unusually old for Fernhill Cemetery, which was founded in 1848.

According to an 1883 book on the Chandler family, in March 1787, Col. Joshua Chandler, his daughter Elizabeth and son William sailed from Annapolis, N.S., to Saint John to settle business matters related to the family estate.

Their vessel was caught in a snowstorm, missed the harbour and ran aground at Musquash Point.

William tried to swim to shore, "but was crushed between the vessel and the rocks and drowned," George Chandler writes.

Col. Chandler, Elizabeth, and others managed to land, but "they were miles from any dwelling and the weather severe. It is said he urged his daughter to leave him . … he then climbed a high point of the rocks for a lookout, from which, being so benumbed with cold, he fell and soon died."

The unhappy Chandlers and Grants died on March 11, 1787, after wandering for days in the woods. They were buried in the Old Burying Ground at the head of King Street.

Seventy years later, they were exhumed on the order of lawyer and judge Amos Botsford and his wife, Sarah Chandler, and moved to the family plot at the newly created rural cemetery.

4. Ruthless assassins

This Gothic column in the old Church of England Cemetery on Thorne Avenue is dedicated to "our most respected and lamented brother James Briggs Jr., aged 23 who was shot by some ruthless assassins as he was passing by the Long Wharf, Portland."

Rioting and violence between Catholics and Protestants in Saint John had reached a fever pitch on Sept. 6, 1847.

Briggs, the son of a prosperous Portland shipbuilder, was leaving a Sons of Temperance meeting when he got into a scuffle with two Irish Catholics, Dennis McGovern and Edward McDermott. He was shot in the head by these two "ruthless assassins" — likely related to his membership in the Orange Order, a Protestant political society.

His murder inaugurated "a summer of unprecedented violence in the histories of Saint John and Portland," writes Scott W. See in the book Riots in New Brunswick.

The resulting vigilantism led to the establishment of a Saint John police force.

5. Storm skeleton

On Sunday, July 6, 2014, parishioners arriving at St. Peter's Church in the north end made a grisly discovery.

An old tree at the rear of the church had toppled in post-tropical storm Arthur, exposing its extensive roots. When they looked closer, they found tangled in the roots was a human skeleton.

The bones were gathered from the church and sent to the coroner.

Police stated the bones "appeared very old and have turned up before from old burials on the property."

St Peter's Church has now been demolished; however, a small graveyard remains.

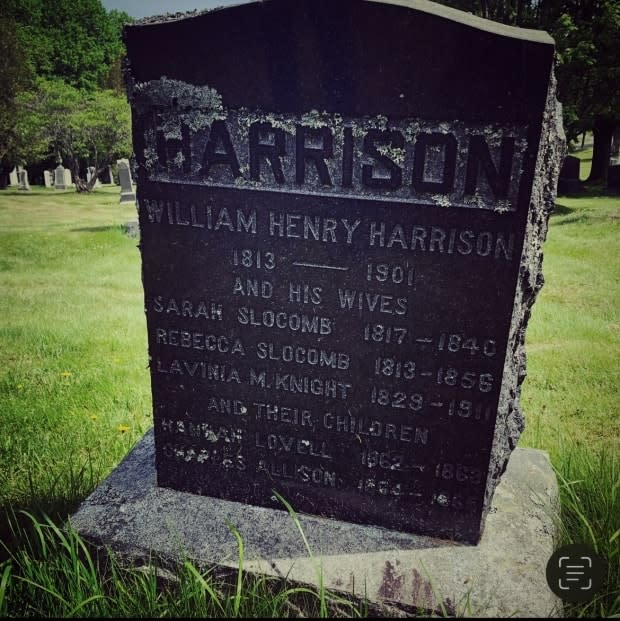

6. Three's a crowd

Unusually, Henry Harrison chose to be buried in Fernhill Cemetery with not just one or two — but all three of his wives: Sarah Slocomb, Rebecca Slocomb and Lavinia Knight

"It was in the past not that usual to have three spouses — but not common to be buried with that many," said graveyard historian Deborah Trask. "It would have been economical to put them all on one stone."

One can imagine the spirited conversations thrifty Harrison and his three wives might be having in the afterlife.

7. Seances, priests, and urban legends

Local lore holds if you dare to peer into the crack in this pyramid-shaped grave in Fernhill Cemetery at night, you'll see a knife or a pair of scissors, allegedly a murder weapon, glinting in the moonlight.

It's a spooky story — and an urban legend. But the real story of Rev. William Thomas Wishart is almost as eerie.

Wishart, born in Edinburgh in 1809, was a controversial, bombastic man of God who preached at St. Stephen Presbyterian Church on the corner of Charlotte Street and King Square North.

His sermons were so unorthodox he was eventually brought before a court of the church and deposed from the church in 1846.

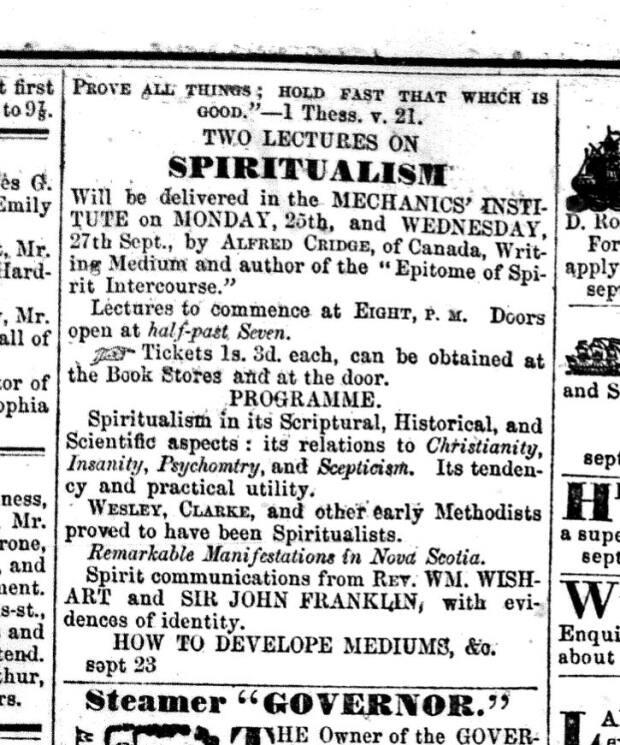

But his preaching, apparently, didn't end after his death in 1853. In 1854, two self-styled spiritualist mediums from Nova Scotia, Alfred and Annie Cridge, advertised in the local papers they had received "spirit communications from Rev. Wm. Thomas Wishart,'' which they would share along with other "manifestations" at a public lecture.

The Cridges toured North America communicating with the spirits through table-rapping, automatic writing and psychometry — the debunked "science" of "reading" objects and divining information about the person to whom they belonged.

Exactly what unorthodox messages Wishart allegedly conveyed from beyond his pyramid-shaped grave remain a mystery.