A Closer Look at Krishna Sobti’s Game-Changing Works and Firebrand Feminism

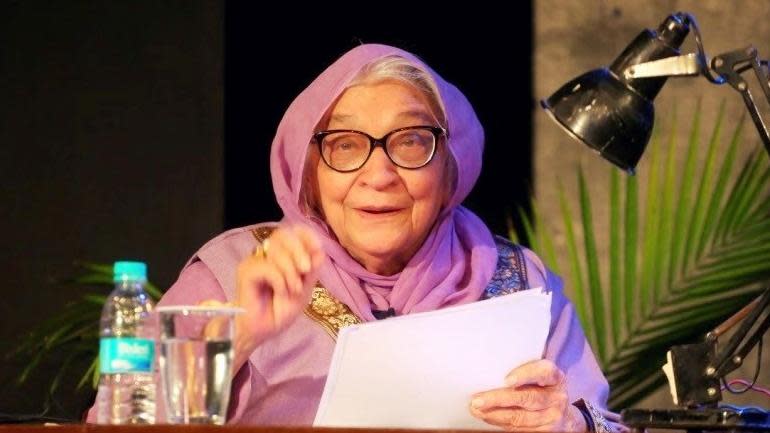

Krisna Sobti, who passed away in 2019 at 94, is often referred to as the Grand Dame of Hindi Literature and a fiery voice among the second wave of Indian feminist writers - joining the ranks of Ismat Chughtai, Mahadevi Verma, and Amrita Pritam.

Krishna Sobti didn’t like the word “woman author” attached to her persona. According to those who studied her—as much as they studied her work—it set the cap for being seen as more “woman” and less “author”.

This simple observation speaks volumes about the late author, revered for her no-holds barred attitude and literature, which was brimming with feminist ideology at a time when the very concept was alien, and frankly, blasphemous to Indian society.

Sobti, who passed away in 2019 at the ripe age of 94, is often referred to as the ‘Grand Dame of Hindi Literature’ and a fiery voice among the second wave of Indian feminist writers—joining the ranks of Ismat Chughtai, Mahadevi Verma, and Amrita Pritam.

The legacy left behind by these women is a rich one, not only because their work aimed to smash and expose the patriarchy rooted in this country, but because they made their words known through vernacular languages accessible to all. An important point to note, considering that even today “feminism in India” is deemed a “recent” phenomenon practised by the English-speaking urban privileged.

Their works celebrate the fiercely independent spirit of a woman. Be it Chughtai’s Kaghazi Hai Pairahan (The Paper Attire) or Sobti’s Mitro Marjani (To Hell With You, Mitro), the authors contributing to this unspoken and unofficial movement created a powerhouse of women characters who refused to be typecast into patriarchal roles reserved for them.

More often than not, both Sobti and Chughtai’s writings used their protagonist to exert her sexual liberation and independence—a running trope in their work to signify the character’s demand for freedom.

Sobti was born on February 18, 1925, in Gujrat city, now in Pakistan. Post-partition, she moved to Delhi, and after completing her education along with her three siblings, she worked as a governess to Maharaja Tej Singh, the child King of Sirohi in Rajasthan.

A refugee from Lahore, a migrant from Delhi, and in a unique position of being a woman seeking employment, Sobti often drew from her own experiences to channel her female characters. Naturally, her work also reflected stories around Partition and the relationship between a man and a woman.

Another distinctive feature of Sobti’s work was that she almost carved out her own language: a fusion of Hindi and idiomatic Urdu coupled with the risqué flavour of Punjabi. The combination led to a tone of familiar and rough—in her esteemed works. Like her enigmatic self, her writing tone and language also adapted through the years: a feat not uncommon to the storylines greeting her characters. As a result, her protagonists were often bold, outspoken, and self-sufficient women hungry for change.

While Sobti’s work—panned over decades—has a range of characters, similar and unique, the background to the narrative was equally important, because it drew from the reality of the times.

For instance in Mitro Marjani (1966), the Gurudas household is, as expected, governed by patriarchal laws and mannerisms congruent to the age. And then in comes Mitro, the second daughter-in-law, with her curious mind, challenging words, and unapologetic sexual desires. In a budding and blatant sweep, Mitro challenges the social norms of the times by demanding to be fulfilled sexually, even as her husband and his male family members attempt to use physical strength in forcing her to subdue her “loud” body language.

But Mitro is not one to be subdued. A translated line from the text reads: ”The dullards! Had they any manhood, they would have either licked me all over with relish or torn me apart like a lion.”

She is defiant in her belief, and tells anyone who will listen that she is more than capable of producing an army of children, it is her husband who needs to be more virile. Through Mitro, Sobti asserts an identity of a woman who does not apologise or shy away from her sexual desires, who is in control of her body: an almost anomaly for women, especially married women, of the ages.

Sobti was also known to present the ugly realities that were met by women of the times. In her novel Surajmukhi Andhere Ke (1972), she forayed into the psyche of a woman who had been raped in her childhood, a trauma which imprinted in her mind and led her to grow up with a bitter and frigid personality, one that dispelled later when she finally was the recipient of love and respect.

In Dilo-Danish (1993), Sobti examined the grey territory of infidelity in a sense, speaking through the voice of her protagonist: the young and beautiful Mahak, the daughter of a courtesan, and her love story with Kripa Narayan, her patron, a distinguished lawyer and the father to her two children. Set in the first quarter of early-20th century Delhi, the book also bravely examines the feelings of Narayan’s wife, Kutumb Pyari. Her narrative broached no prejudice or plights of moral dilemmas. It simply presented a story, not unknown or untold.

In later books like Samay Sargam (2001), Sobti also touches upon subjects often overlooked: the desires of old age. Through her leading lady Aranya, Sobti breaks the norm of “old age begets loneliness”. If anything, Aranya revels in her solitude, confident in her ability to look after herself. She shares companionship with her old friend and neighbour Ishan, but the novel centres more on her peace with her independence and ageless mind.

Sobti was awarded with the Sahitya Akademi Award for Zindaginama in 1980 and appointed a Fellow of the Sahitya Akademi, India's National Academy of Letters, in 1996. In 2010, she was offered the Padma Bhushan but she declined it, stating the need to keep a distance from the establishment.

Also watch: Exclusive interview with writer, poet and activist Meena Kandasamy.

In 2015, she returned the Sahitya Akademi Award and her Fellowship following the riots in Dadri, stating that the government wasn’t doing enough on that account. She also raised concerns regarding the freedom of speech in the country. In 2017, she received the Jnanpith Award for path-breaking contribution to Indian literature

Sobti was also awarded with the Hindi Akademi Awards, Shiroman Awards, Maithli Sharan Gupt Samman: some of the many accolades filling her cap and creating a legacy that will inspire many generations to come.

(Edited by Kanishk)