Airborne telescope captures lunar shadow during N.B. eclipse

Monday's total solar eclipse may be over, but the excitement continues for a retired scientist who captured the rare event with a balloon-borne telescope.

David Hunter, from Florenceville-Bristol, was already squarely in the path of totality — where the moon fully covers the sun.

But his project sought to get even closer, and to livestream the eclipse in real time in case of cloud cover, by attaching a payload with five cameras and a telescope to a large balloon.

Even with clear skies, the livestream on YouTube had 16,000 views as of Wednesday.

Retired scientist David Hunter holds the payload, containing computers and cameras, ahead of the launch. (Ed Hunter/CBC)

Images recovered from the payload show the moon's shadow progressing across the earth during the eclipse, a feature most wouldn't have seen so clearly from the ground.

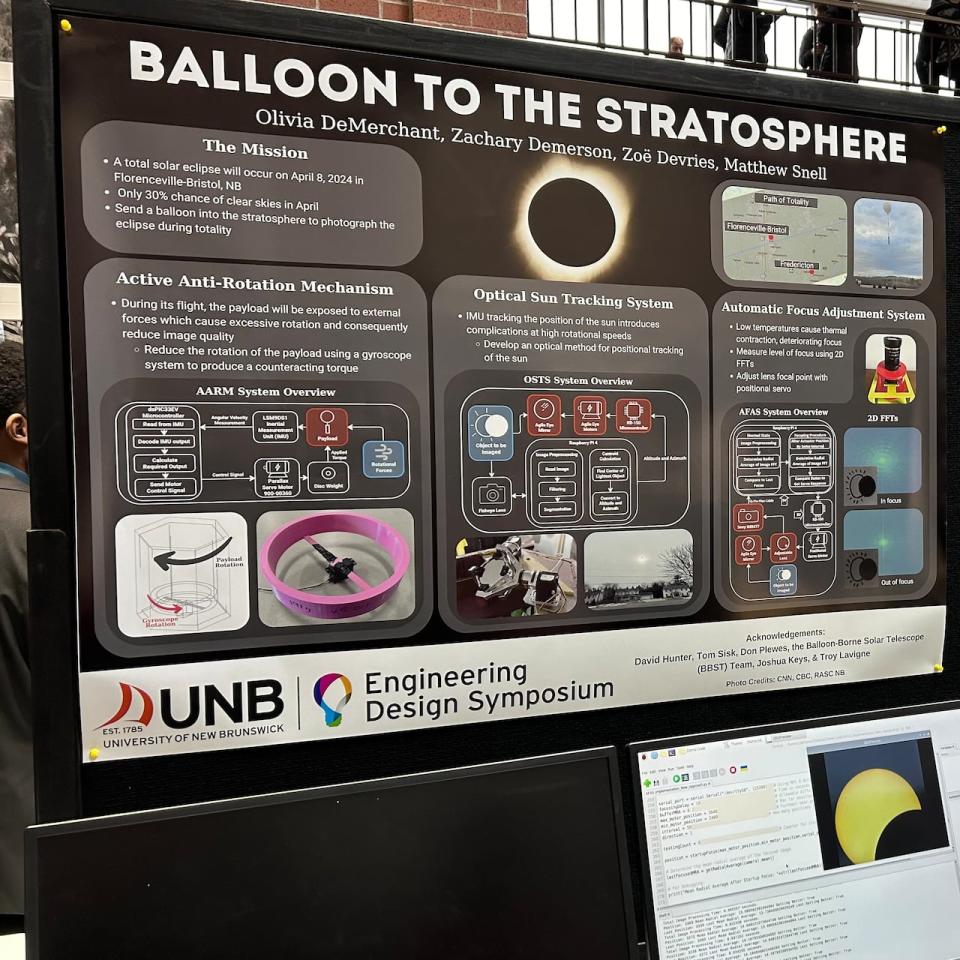

University of New Brunswick students Olivia DeMerchant and Ethan Garnier were part of engineering and design teams that made capturing those images possible.

DeMerchant was tasked with finding a way to keep the six-foot-tall payload from rotating away from the sun, while Garnier worked on an electrical system to track the sun's position.

WATCH | Ride along with the payload recovery team:

The livestream back to earth proved useful to DeMerchant, who was able to tune into the launch in Florenceville-Bristol from Fredericton.

While Garnier saw the launch in person, he said it was equally exciting to see the payload images.

"There was one [image] where, once it got up to the highest altitude, you could see the curvature of the earth and the blue aura around it," Garnier said.

"It's actually a breathtaking picture."

University of New Brunswick students designed a mechanism to limit the rotation of the payload, so that its cameras could properly track the sun. (Submitted by Olivia DeMerchant)

There was one notable snag, Hunter said, as the camera failed to capture the moment of totality.

That's because a protective solar filter placed over the camera didn't work as planned.

"At time of totality the filter was supposed to be removed and enable us to see the corona," Hunter said.

David Hunter and his team launch a balloon-borne solar telescope in Florenceville-Bristol ahead of the total eclipse on April 8, 2024. (Ed Hunter/CBC)

"For some reason, which we haven't analyzed yet, the filter got stuck halfway. So that ruined that part of our imaging …Fortunately, because it was clear, we could see it from the ground."

The launch itself proved memorable for Hunter's team and onlookers alike, especially as the winds picked up.

"It was very touch and go. Inflating the balloon, it was bobbing all around on the ground and it could have been destroyed on the ground," he said. "It was a great relief to get it up in the air."

Monday was the balloon's fourth time getting off the ground, Hunter said, but the first time with clear skies.

"When we launched the balloon before, it went up. We could see it for a short while, then it would go through the clouds and we couldn't visually see it," he said.

"But this time, it was amazing … you could visually watch it with your naked eye or with binoculars during this flight, it was pretty cool."

Hunter's balloon was equipped with five cameras, one of which had a telescope attached, to capture the moments leading up to and during the total solar eclipse. (Submitted by David Hunter)

While the balloon could travel as high as 30 kilometres, Hunter said Monday's flight was limited to about 20 kilometres.

"We had to limit its height because we wanted it to still land in the province," he said. "I had been afraid that it was going to go farther south down to … the Gagetown military base or in the Bay of Fundy."

Within a few hours, Hunter said, three volunteers were able to recover the payload just south of Mactaquac Provincial Park.

"The whole thing wasn't perfect, but from our point of view it was pretty close to what we wanted," he said.

While people have sent balloons up during eclipses before, Hunter said this project was unique in that it used a tracking telescope and livestreamed images during the event.

Hunter's next step will be to analyze temperature, pressure, height and movement data collected by the payload.

"We hope to recover information, flight data ... that might be useful for future flights or people to do something similar," he said.