Alex Honnold Takes Us into the Great Indoors

People do all kinds of wild things these days in an attempt to feel better and restore themselves to their original state: We freeze in cryogenic chambers, slow-roast in infrared saunas, submerge in sensory-deprivation tanks. We eat charcoal and foraged weeds and beige porridges made from ancient biblical grains. We fly great distances to puke and hallucinate at ritual ceremonies in South America. It's as though, collectively traumatized by the monstrous pixelated future we have created, we are in hysterical pursuit of the primal. Lately we seem to be finding it in rock climbing.

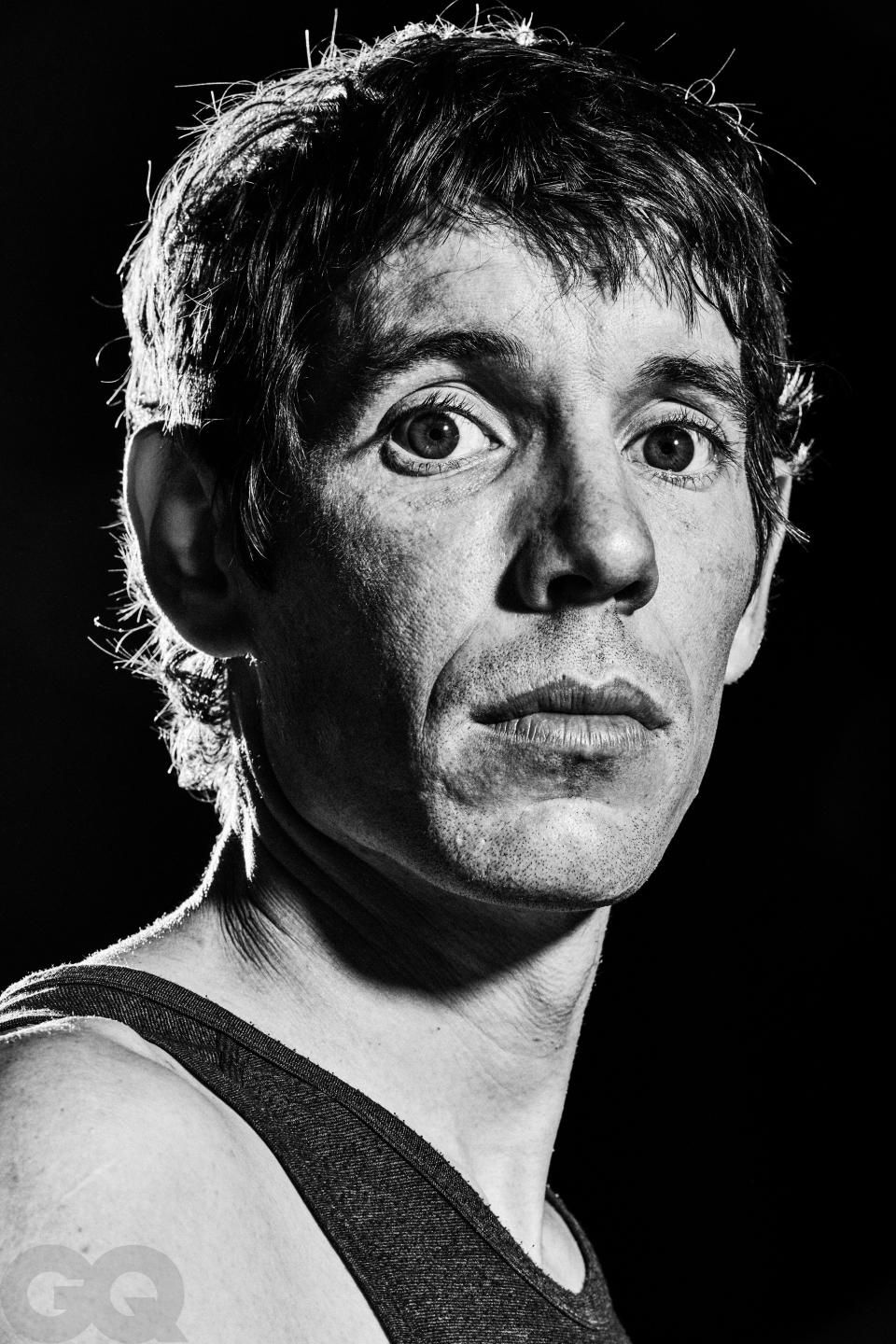

“There's an innateness to it,” says Alex Honnold, the most famous climber on the planet. “We are primates. We're great apes. We are hardwired to move in this way.”

If you are a member of recreational climbing's still dominant demographic—à la Honnold, a white male between 18 and 35, though the sport is approaching gender parity and racial diversity is also on the rise—it's probable that you or someone you know has recently caught the fever. Instagram is lousy with glamour shots of attractive millennials sending boulder problems, and celebrity fans include Frank Ocean, Jason Momoa, Brie Larson, and Jared Leto. In the lead-up to the sport's Olympic debut this year in Tokyo, there are more competitions and gyms dedicated to climbing than ever before. The primitive impulse might partly explain the frenzy, since along with running and swimming, climbing has been a basic way the human animal has negotiated its environment for millennia. But the sport's core values—rugged individualism, self-actualization, performance efficiency, crowdsourced problem-solving—also position it as a uniquely attractive recreation for our tech-optimized, permalancing, late-capitalist moment. The arrival of modern gyms tricked out with coworking spaces, REI outposts, conference rooms, cafés, and craft beer (not to mention a built-in like-minded community) has turned climbing into a full-on lifestyle choice: You never have to leave.

Fans of Honnold are already familiar with his most legendary accomplishment: On June 3, 2017, he became the first person to scale El Capitan, Yosemite's vertical granite slab, without a rope or safeguards of any kind, as captured in the Oscar-winning documentary Free Solo. Nobody knew whether the ascent was even possible, and it certainly wasn't advisable, and the crew working on the movie—many experienced climbers themselves—had to consider the horrifying prospect that they might actually be making a snuff film. Honnold set out before dawn and summited while the breakfast buffets were still open. His (characteristically moderate) reaction upon making history after 3 hours 56 minutes: “So delighted.”

The word inspiring has been degraded through overuse, but there's no other way to put it: Alex Honnold's El Cap climb was truly, excruciatingly inspiring—a feat that transcended sports and probably even art. In it he articulated the direct confrontation between humanity and eternity that most people dedicate their lives to avoiding. Jimmy Chin, the climber and filmmaker who, with his wife, Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi, codirected Free Solo, helps put the singularity of the achievement into context: “It would be the Hail Mary from half-court at the NBA Finals, except that if you didn't make it, you die.” Then he revises the metaphor: “You have to make every single shot you take in that game or you die.”

A few nights ago, Honnold was bivouacking off the side of El Cap, sleeping under the full November moon. With his friend Tommy Caldwell, a fellow elite pro, he'd spent the season laying a new route up the wall and had returned to strip rope and clean up. Today, Honnold, an in-demand speaker on the corporate/TED/VC circuit, participated in a discussion on risk management for a group of venture capitalists (the partner who moderated is a big ice climber). Now, well after dark, he is at a soon-to-open franchise of Planet Granite, part of the country's largest group of climbing gyms (for which he is a board member), near an industrial park off the freeway in Fountain Valley, California, modeling fashion pants.

“It's all a life experience,” Honnold says, sitting in a modified lotus position, barefoot, having swapped out the Prada in favor of shorts and a tank top. “At this point, there are a lot of things I do in my life where I'm like, My body is a piece of meat that's being used by others. That's fine, that's interesting, whatever.”

Even late at night, in a fluorescent-lit warehouse, Honnold is alert, thoughtful, efficient, emitting the low-frequency zen of someone who spends much of his time in the wilderness. He speaks neatly, in complete sentences. Though friendly and game, he isn't inclined toward hyperbole or the ingratiating tricks of conversational mirroring. The closest he comes to swearing is the occasional “freakin' ” or “jeez.”

It turns out that achieving the sublime doesn't comprise one grand, dramatic gesture so much as a series of small, rational preparations. As Honnold describes in his main-stage TED Talk, the grand achievement comes from meticulously breaking down big goals into small chunks and then grinding each one till you've cracked it open. Ultimately, this collection of small, solved problems can become, in the zoom out, a giant mosaic: sweeping, dramatic, profound. Scaling El Cap without ropes is the mosaic.

“When I first started climbing, it was pretty fringe. It was usually the misfits that didn't belong. Now it's a thing.” —Free Solo Codirector Jimmy Chin

“That was freakin' heinous for me,” says Honnold of the TED Talk. “The irony is that I found it really hard to prepare for that. Because if I spent an hour trying to memorize and practice, it felt like pulling teeth. Whereas I can spend hours and hours at the gym. It's easy to spend six hours training for something that you love doing.”

Honnold formalized his interest in the sport at age 11, when his parents took him to the Granite Arch Climbing Center near Sacramento after reading about it in the paper. He was hooked from the start, consuming classic manuals like How to Climb 5.12 and trying to incorporate the lessons on his own. “I was really shy, I didn't like team sports,” he remembers. “I didn't hang out with other kids that much.” After dropping out of Berkeley after freshman year, he committed himself to the life of a climbing dirtbag—the die-hard band of peripatetic, van-dwelling, subsistence-living climbers—that's anti-materialist by definition.

“When I first started climbing, it was still pretty fringe,” recalls Chin, now 46. “It was usually the misfits that didn't belong, either in mainstream sports or society. Now it's a thing. The dirtbag lifestyle is now something people aspire to in their $100,000 Sprinters.”

Recent data attests to a surging, lucrative industry: Per the Outdoor Industry Association, approximately 7.7 million Americans went climbing in 2018, more than ever before, and two years ago, climbers injected nearly $12.5 billion into the economy—mainly through travel but also on gear and gym memberships. According to Climbing Business Journal, 2018 was also the industry's most successful year on record, with 50 commercial facilities opening domestically, bringing the total number of commercial climbing gyms in the U.S. to 517.

“At this very moment, there is way more demand than there is supply,” says Jeremy Balboni, CEO of Brooklyn Boulders, part of the new generation of climbing facilities whose first location opened in 2009. Even 15 years ago, Balboni says, there were few appealing options for indoor climbers. The sport had been relegated to lone rooms of regular gyms, invite-only private walls, and badly lit, uninspired climbing facilities in outlying neighborhoods. “We looked at [climbing] and we said, ‘This is an amazing sport that should be put on a pedestal and brought to a bigger audience.’ ” Brooklyn Boulders' flagship gym, in the Gowanus section of the borough, opened with graffitied walls and live music. “The response was immediate,” says Balboni. The company currently has five locations, with five more on the way, offering everything from yoga classes and summer camps to comedy nights and drum circles.

“People will come on their off day to work, or to hang out with their friends, because of the environment itself,” says Balboni. “It feels really good in there.”

“I actually kind of hated it at first—it's kind of scary. You have to get used to the heights, obviously,” says Jolie Ruben, 32, a photo editor in New York City who has been climbing for five years. Bored with the regular gym, she was introduced to climbing after her then boyfriend (now husband) caught the bug. “Once you start reaching the top of things, doing a little bit better, you fall in love with it. It was really rewarding having this activity where you're literally holding your own weight.”

Ruben climbs primarily for the workout and acknowledges that the social engagement and community spirit of the climbing gym required a bit of an adjustment. “Normally you're in a regular gym and you don't even make eye contact. Everyone's doing their own thing. That was the big difference for me,” she says. Ultimately she converted to climbing's distinct style of camaraderie. “It's one of those things you don't realize until you go through it yourself. When I'm up on the wall and a stranger's cheering me on, I'm not like, ‘That's weird; she doesn't know me.’ I'm like, ‘Oh, that's awesome—that's pushing me to do better.’ ” Ruben now climbs about twice a week, usually with her husband but also with friends and colleagues, and credits the sport with toughening her mental game: “It's definitely [about] overcoming thinking that I can't do something, that I can't get from one hold to the other.”

Marie Buckingham, a 15-year recreational-climbing vet who has climbed all over the world, extols the sport's physical and mental rigor, the way it insists you get comfortable with your own vulnerability: You can't bullshit your way up a wall. “It requires you to be present, to really challenge yourself,” she says. “There's not much cheating you can do to get better at rock climbing. You have to build your discipline and your strength and your conditioning over time. When you're climbing, you're not thinking about your task list from work or whatever your best friend said to you last week that you feel weird about.” Buckingham, 31, estimates she's met at least half of her closest friends through climbing. But she points out that the sport's etiquette, including its vast insidery lexicon, is potentially alienating to beginners. “There's so many ways to describe movement, shapes of holds, friction, weather patterns—people call this beta, like information. Part of the barrier to entry is understanding what the fuck people are talking about.”

Unlike its dirtbag forebears or the auras surrounding other sporty subcultures—skating's legacy of punk defiance, the existential poetry of surfing—climbing's new wave isn't especially affiliated with cool. If cool is about casual detachment, climbing is about literal and figurative attachment, a concerted state of mental and physical engagement that requires nerd levels of exactitude. In climbing, you try and you care. With its work ethic and goal setting and math-y language (beta, problem, projecting, redpoint) and unembarrassed communal enthusiasm, the modern climbing gym is almost ruthlessly wholesome, more like a church than a bar. You might do it wearing funny slippers, but the sport itself is not known for its silliness or frivolity or biting wit. As Honnold puts it, “To a certain extent, climbing is kind of serious. You don't joke around too much. No sudden movements, nothing weird. Because the thing is, a lot of time in climbing, if something goes sideways, you could actually die.”

“It's the same way that CrossFit has a certain tribalism to it, except that climbing is way more chill and way more fun.” —Alex Honnold

As in a church, there's a certain amount of proselytizing. When he learns I've never climbed in a gym, Honnold offers some advice. “Go to Boulders, prime time. It'll be throngs of people, masses huddled around, all chitchatting, mostly people lying on the pads while one person climbs. They fall, you sit for a while, you chat. It's incredibly social.” With bouldering, he explains, “you have eight people trying the same problem. One person tries it, they all talk about what they did, what they could have done differently, what they did better. And then when you're tired, you just lie there, ‘Oh, so how was your Friday?’ ” He describes another gym he visited in Seattle that epitomizes the new climbing lifestyle: “It's all just people writing code upstairs and then bouldering for a couple of hours, then taking some meetings.”

He adds, “I think a big part of the rise of gym climbing is the fact that it's a really fun, community way to stay fit. It's the same way that CrossFit has a certain tribalism to it, except that climbing is way more chill and way more fun.”

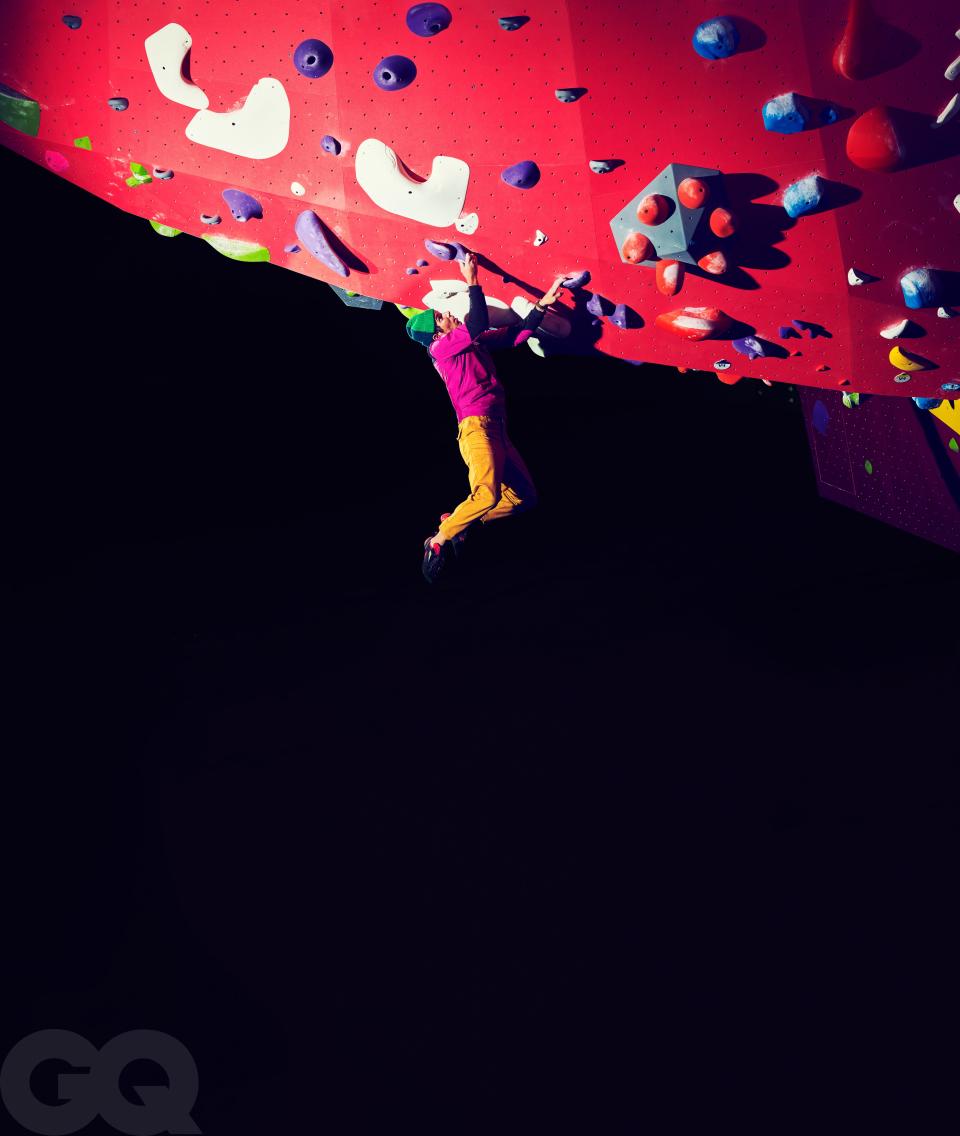

But with popularity comes change. The rise of competition climbing means many new facilities are catering to those flashier leaps and dynamic swings instead of to the more classical movements one might make in nature. And whereas gym climbing was once mainly considered a training ground for outdoor goals, now there's a membership of newbies who may have no intention of ever climbing outside at all.

“You have a large community of people who just like climbing inside recreationally, and they're totally content with just casually going in and having fun for the afternoon and calling it good,” says Cliff Simanski of GP81 in Brooklyn. An experienced climber and route setter, Simanski, along with his partners, sought to go in the other direction, minimizing distractions and returning to a more purist approach: no marketing, no youth teams, no menu of other fitness classes. “A lot of what we try to do is avoid some of that parkour-style stuff and use more simple moves and climbing techniques that you do encounter outside,” he says.

Honnold also observes a sea change in the scene. “To me the biggest indicator is that if I do events, if I speak at a climbing gym, the majority of climbers now have been climbing for fewer than three years,” he says. “I realize it's a completely different climbing culture. They don't know the same climbing gear I had growing up, they don't know the same stories. It's like, ‘Oh, wow, there's a lot of climbing history that's disappearing behind now.’ ” But, he adds, “I'm fully into it. I'm a sponsored rock climber. The more people rock climb, the better that all of us in the industry do. If others get even a tiny fraction of what I've gotten from rock climbing, that's incredible.”

Honnold, who uses gyms for training and recreation, points out that this new wave of gyms radically improves opportunities for climbers of all abilities. He gestures around us. “When I look across this wall—some of these routes are completely different styles, completely different techniques. Some of them, you're all laid out sideways, doing crazy maneuvers; some of them are straightforward power, a pure test of finger strength. It might not be quite as varied [an experience] as the outdoors, but in terms of movement, you can probably get more varied movement indoors, because you can create anything you want in here. You're limited only by your imagination.”

Outdoor climbing, though, introduces an ethical and spiritual dimension that you can't access in a gym. Beyond the principles of “leave no trace” environmental stewardship, climbing outside is a constant, humbling reminder of your small place in the grand scheme. “You just get worked by nature all the time,” says Honnold. “It's cold, it's windy, it starts to rain. No matter how big your ego is, no matter how many people have told you that you're the man, as soon as it starts to rain, you're getting cold and wet.”

After Free Solo, Honnold could've gone for the crass cash grab—appearing on Dancing With the Stars (though that is extremely hard to picture) or slapping his name on a line of gear—but as Chin notes, “he doesn't care about fame and money. The intent is very pure.” Still, Honnold fully appreciates the way the attention has changed his life, from how he makes a living (more sponsorships, more partnerships, more speaking gigs, more opportunities) to the impact that his eponymous foundation, dedicated to environmental work, can make. The push-pull between drive and domesticity, a major theme of the film, continues to reverberate for him: He's still with his girlfriend, Sanni, and he seems curious about ways to reconcile the work-life balance moving forward. It's a new problem to solve, another goal to set.

Honnold hasn't been a reluctant ambassador to climbing, but being its public face was never his dream. With climbing coming to the Tokyo Olympics this summer, there are new athletes and heroes waiting in the wings—he mentions Brooke Raboutou, a young American climber who recently qualified for 2020—and he'll be happy to pass the baton when the time comes. “I can't wait, I'm ready to hand it off,” he says. “I'm gonna pull down my hood, I'm gonna walk out the back, and I'm gonna go climbing.”

Caroline McCloskey is a writer living in Los Angeles. She wrote the June cover story on Seth Rogen and the October profile of DJ Harvey.

A version of this story originally appeared in the February 2020 issue with the title "The Great Indoors."

Watch Now:

Alex Honnold Goes Undercover on the Internet

PRODUCTION CREDITS:

Photographs by Eric Ray Davidson

Styled by Jon Tietz

Grooming by Johnny Hernandez for Fierro Agency

Tailoring by Yelena Travkina

Production by Tricia Sherman for Bauie Productions

Special thanks to Planet Granite, Fountain Valley, California

Originally Appeared on GQ