Alzheimer’s disease memory loss reversed in mouse study

Memory loss caused by a form of Alzheimer’s disease has been reversed in mice by scientists who hope it could eventually benefit dementia patients.

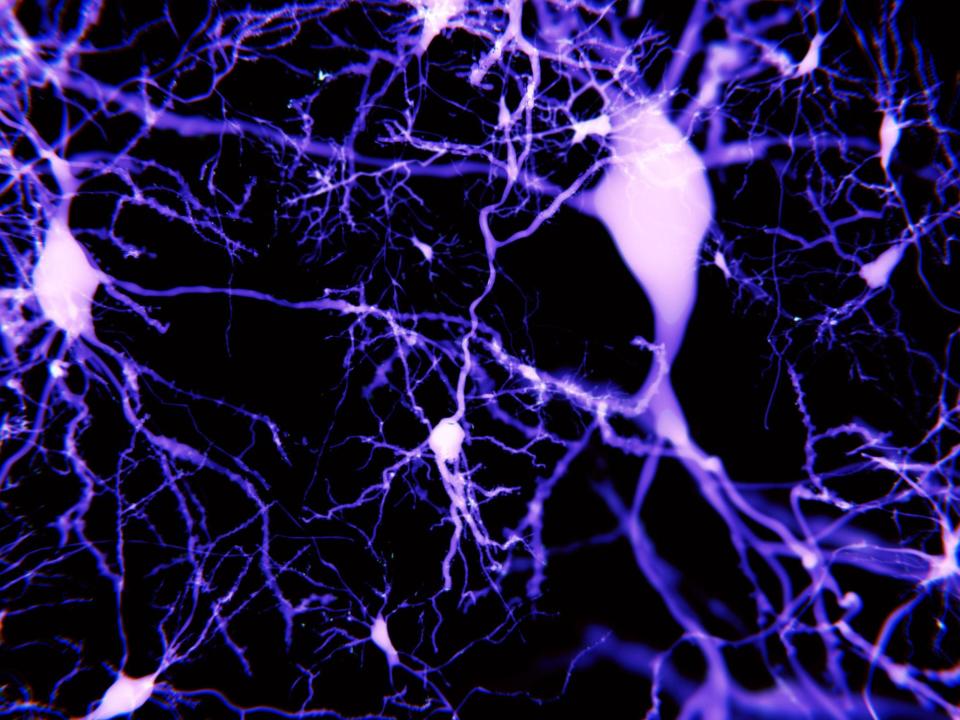

Researchers at the University of Buffalo identified that the disease interfered with neurons ability to transmit electrical signals in parts of the brain responsible for memory formation.

The most common cause of dementia, Alzheimer’s disease is in-part because it is caused by a complex mix of lifetime risk factors and genetic traits. There are currently no treatments to cure or consistently delay its progression,

The scientists looked at genetic changes which affect how DNA instructions are read and expressed in cells – known as an epigenetics – rather than changes in the sequence of DNA.

By deciphering what epigenetic changes might intefere with the signalling between neurons and cause memory loss, they were then able to propose drugs that could restore it.

“We have not only identified the epigenetic factors that contribute to the memory loss, we also found ways to temporarily reverse them in an animal model of Alzheimer’s disease,” said Professor Zhen Yan, senior author of the study published in the journal Brain.

Alzheimer’s causes the gradual deterioration in thinking skills and memory. Most research has focused on tackling the build-up of toxic clumps of abnormal protein molecules which are the hall mark of its progression.

Professor Yan and colleagues looked at a different factor impacting memory formation.

They found that neurons in the brain’s frontal cortex were gradually losing receptors for a key neurotransmitter glutamate, in parts of the brain responsible for working memory.

Post-mortem examinations of human patients with Alzheimer’s revealed they were also lacking these receptors and led them to a particular group of enzymes which could be affecting the genes responsible for producing them.

“When we gave the Alzheimer’s animals this enzyme inhibitor, we saw the rescue of cognitive function confirmed through evaluations of recognition memory, spatial memory and working memory,” Prof Yan said. ”We were quite surprised to see such dramatic cognitive improvement.”

The improvements only lasted for a week but for the academic and his colleagues are working on refining a delivery method which would allow the drug to reach more of the brain’s neurons and have a more powerful effect.

Independent researchers said epigenetics was one of the major research frontiers for dementia and held promise for providing sorely-needed treatments after 15 years without new drugs.

However the short-lived findings in mice did not guarantee the same effects would occur in humans, or even other types of Alzheimer’s.

“It’s exciting to see drugs coming through that target these mechanisms, but we do need to be cautious,” Clive Ballard, professor of age-related diseases at the University of Exeter Medical School, said.

Dr Rosa Sancho, head of research at Alzheimer’s Research UK, said: “One of the most exciting aspects of epigenetic research is that the changes are potentially reversible, and this study highlights how targeting an epigenetic change could help improve brain function in mice with features of Alzheimer’s disease.

“These interesting findings in mice now need to be taken forward in studies in people, to explore whether they could form the basis of a future treatment approach for people with Alzheimer’s disease.”