'Profound gathering' aims to fuel revival of Tlingit language

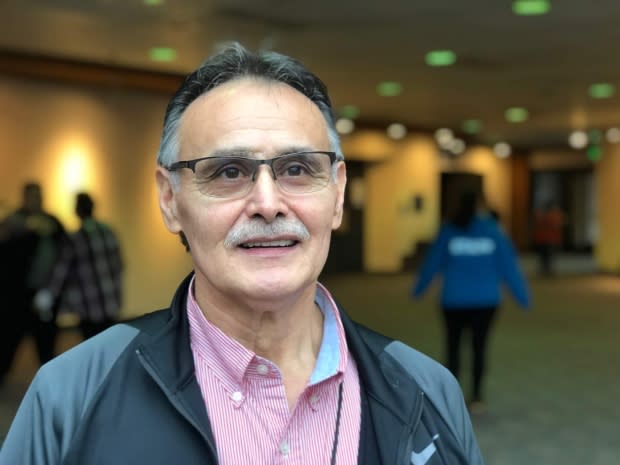

Fred White feels as though he's spent his life watching Tlingit — his first language — slowly inch toward extinction.

"It's a pretty sad situation — like even myself, as fluent speakers, we have hardly anyone to converse back and forth with," he said.

White is a Tlingit translator and instructor who works with the Goldbelt Heritage Foundation in Juneau, Alaska. He's considered to be the youngest fluent speaker of Tlingit.

"First three years that I worked at the Goldbelt Heritage Foundation, I lost three fluent speakers that I worked with, just in a very short time," he said.

"Seems like it's been like that, all of my life."

This week, White is playing a key role as a translator at an Indigenous language conference, in Juneau. The historic event is being hosted by the Sealaska Heritage Institute, a non-profit group that works to preserve Southeast Alaskan Native culture. The conference has welcomed speakers of Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian, from Alaska, Yukon and northern B.C.

So far, it's been an emotional experience for White.

"I just took a break and I was sitting there, sitting in the back there, looking at the elders that we do have," he said.

"A lot of the time ... when I speak to them the way I learned to speak, I don't get the replies I thought I would get. So they're losing their language too. I don't know, maybe it's old age."

Tough to learn

There are believed to be fewer than 200 people around the world who now speak Tlingit. It is considered to be a highly complex language that's not easily picked up.

Still, many of the people at the Juneau conference are keen to try. The event has drawn young people and elders, fluent speakers and keen learners.

"Tlingit ... is one of the hardest languages to learn," said Jeff Leer, a retired linguist from the University of Alaska (Fairbanks) who's specialized in Alaskan native languages.

"And that's why I'm so proud of all these young people that are really taking it seriously and really doubling down on learning the intricacies of grammar and all this."

Duane Gastant Aucoin, who is with the Teslin Tlingit Council in Yukon, is learning. His Tlingit mother was once punished for speaking her language. Now Aucoin has travelled with about 40 others from Yukon across the border to Juneau, to learn and celebrate the language and the Tlingit culture.

"This is just going to be the first of many, many events of our people coming together," he said.

Aucoin describes how he could feel the presence of his ancestors in the room as the conference opened on Tuesday — and how he sensed their approval.

"Yes, it's sad that the language is not like it used to be," he said. "I know our ancestors are smiling because we're getting back there," he said.

The Teslin Tlingit Council passed a Language and Culture Act last year, making Tlingit the official language for the government and the community. Last week, the First Nation approved an implementation plan for the act.

"Language is becoming one of the most important priority areas for Teslin Tlingit Council, as a government," said chief Richard Sidney, also in Juneau this week.

"It's a profound gathering. It's unbelievable, the opportunity to come in and discuss one of the most critically important, fundamental issues that affect our Nation: our language."

'You have to work for it'

Devlin Anderstrom, 21, is from Yakutat, Alaska, and he's one of the younger Tlingit speakers at this week's conference. He describes how he was born into an Alaskan Tlingit family, but then lost touch with his traditional culture for many years when he moved south.

When he returned to Alaska as a teen, he immersed himself in the language and culture.

They're going to be telling stories about when there were so few of us, that we could all fit inside one building. - Devlin Anderstrom

"So I learned, and re-learned a lot of things," he said. "I think the seed was planted in me from the time when I was very young."

These days, Anderstrom is living in Yukon and working to build a relationship between the Carcross Tagish First Nation and the Yakutat Tlingit Tribe. He says he feels a responsibility to do what he can to keep his traditional culture alive, by learning and speaking Tlingit.

"You have to work for it, you have to put the effort in," he said. "It's heavy, but that burden also gives you strength.

"Right now, we're in a bottleneck. And 2,000 years from now, I might have descendents that tell stories about when we almost died out. They're going to be telling stories about when there were so few of us, that we could all fit inside one building."

Fred White sounds less optimistic. He's married to a non-Indigenous woman, so he doesn't speak Tlingit at home and his children never learned the language. He says his grandchildren learn some Tlingit at school, but mostly just some basic vocabulary.

"I don't think they'll ever get into conversational Tlingit ... I don't think it'll ever happen, where we're conversing back and forth with each other," he said.

Still, he's pleased by what he's seen this week, even as he worries about the future.

"It does make a lot of the elders happy. That's good," he said.

On Thursday, word came to the conference that an elder from Metlakatla, Alaska — one of the last fluent speakers of Tsimshian — had been hospitalized. Donations, in Canadian and American currency, were immediately collected.