New Arctic coast highway opens up remote Tuktoyaktuk

Balancing on top of a wobbly plastic bucket in his backyard, Joe Nasogaluak wielded an electric chisel with complete ease. Each time he sliced away at the two-metre slab of rock, a fine white powder flew through the air, coating his clothing and safety glasses.

But he could see his latest sculpture taking shape.

"The piece I'm doing is an Inuvialuit harvester," he said.

Nasogaluak, 59, is a renowned carver who has produced pieces for former prime minister Stephen Harper and hockey legend Bobby Orr. A sculpture he carved out of a bowhead whalebone is on display at Vancouver International Airport.

But Nasogaluak admitted that as a child, he felt trapped in his remote community on the shores of the Beaufort Sea.

"I felt I'd never get out of this town," he said. "I grew up with no money."

In Nasogaluak's childhood home, there was no running water or flush toilets, but Tuktoyaktuk was home and it was all he knew — until he had the chance to go to Toronto for a two-week student exchange.

"It was so good to see the world and I came back to a little village and I wanted to see more."

However, trips away were rare and costly. While there was an ice road south during the winter, in the warmer months, the only way in and out of "Tuk" was by plane.

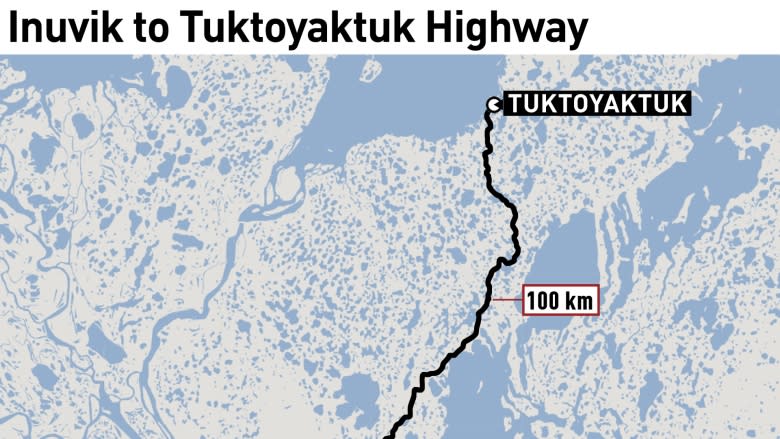

But that is all about to change. By mid November, a 137-kilometre all-season road will permanently connect Inuvik and Tuktoyaktuk, opening up the isolated hamlet in a way it never has been before.

"I think it's the greatest thing that happened in Tuk in my lifetime," said Nasogaluak, grinning.

As a father of five, he's excited for what the road will mean for his children and for all the young people in the community. About a third of the 900 people who live in Tuktoyaktuk are under the age of 15.

He believes they will have more opportunities to travel and will develop a stronger connection to the rest of the country.

"It'll take generations, but they will grow up feeling that we're tied into the other world."

In addition to the new sense of freedom, residents are hopeful that the road makes life in Tuk cheaper and more convenient. The 30-minute flight to Inuvik can cost a few hundred dollars each way and prices for groceries are exorbitant, particularly for produce and perishable items.

But amid the excitement, there is a palpable unease about the kind of change the highway could usher into the community. Some feel Tuk's isolation provided protection from outside influences, like drugs and alcohol. If the highway is going to throw the gates open to the hamlet, many are asking: What will be the long-term benefit?

Decades in the making

The idea of a permanent road to Tuktoyaktuk has been bandied about for decades, and local leaders have persistently lobbied the territorial and federal government to fund it.

In 2013, the federal government committed to paying two-thirds of the $300-million cost. At the time, Prime Minister Stephen Harper spoke about completing the dream of "Macdonald and Diefenbaker" by building a road that would link Canada's three coasts.

Beyond the patriotic symbolism, the Harper government was focused on Arctic sovereignty and resource development — and a road to Tuktoyaktuk would help on both of those fronts.

During the 1970s and '80s, Tuk was a hub for energy companies exploring vast oil and gas deposits offshore. Boarded-up work camps and crumbling equipment are still scattered throughout the community as rusty reminders of a busier time.

Many living in the north hoped a permanent road would revive a stalled industry and encourage more investment in the area. But that is unlikely to happen in the near future, as the political and economic landscape has shifted dramatically in recent years.

While a handful of companies hold exploration licences for the region, last December, the Liberal government put in place a moratorium on any new drilling in the Arctic.

It's bad timing, said Nellie Cournoyea, who served as premier of the NWT during the 1990s and was a longtime chair of the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation.

"People are still here, people want to work, people need jobs," said Cournoyea.

About 400 jobs were created during construction of the highway. But now that the work is nearly complete, people are wondering what's next.

Tuk's unemployment rate is 30 per cent, and with the highway likely not being the road to resources some hoped it would be, local officials are pivoting, trying to entice tourists to head north.

"We are going to do our very, very best to show Tuktoyaktuk as one of a destination point, but we have a lot of competition with other areas who are ahead of us," she said.

Tourists wanted

For the past 10 years, Kylik Kisoun-Taylor has been running Tundra North Tours, a company that offers day trips from Inuvik to Tuktoyaktuk, among other packages. He typically brings in three groups a week during the summer, and his clientele, most of whom are retirees, make the trip by boat and by plane.

"I think as far as tourism goes, [the road] will open up a lot of doors," said Taylor.

Tours to Tuk are now billed as being a journey to an inaccessible locale. But once the road opens, he said the destination becomes more important.

He has been working to diversify his business since construction on the road began and will be offering more tours to other areas, like traditional whaling camps. He's hoping that the hamlet will have more tourist infrastructure in place by next summer.

"I am hoping that people will be organized enough to … have something here for [tourists], so it's not just, you know, you dip your toe and turn around and go back," Taylor said. "You want people to stay for a least a day or two."

'Concerned, but at the same time excited'

At the moment, there are very few services in place for visitors. There are no restaurants and limited accommodations, although the community does plan on creating a campground by next year.

Benches and picnic tables have recently been installed along the shoreline, and over the summer, several residents were hired to paint homes in bright colours. The paint was donated as part of a plan to beautify Tuktoyaktuk.

"It gives everybody a bit of a lift," said 52-year old Stanley Felix, as he rolled a fresh coat of purple paint on the side of a wooden house. He also admitted painting gave him something to do besides "hunting, fishing and worrying about money."

By the end of August, more than 14 homes in Tuk had been painted in bright hues.

While Felix is all for sprucing up the community, talk of the new road elicits mixed emotions. He described his feeling as "scared, concerned, but at the same time excited."

While he believes it will bring new opportunities, particularly for locals who can offer hunting and guiding groups, he is nervous about what else the road could be opening Tuk up to.

"Hard drugs — that scares me," he said. "I know there's gonna be a bit more alcohol. That's a concern for everyone in our community."

Bootlegging has been a constant issue in the community, which is why in 2010, the hamlet put alcohol restrictions in place in an attempt to limit the amount of booze being brought into Tuk.

Residents are allowed up to 48 cans of beer, or just over two litres of liquor. But in recent years the RCMP has made numerous seizures, including one in June where officers discovered 25 bottles of vodka that had been smuggled up on the new highway.

For all of its positive aspects, Felix fears the new road could alter the character of the community, and make it easier for outside influences to erode the way of life and weaken the strong sense of Inuvialuit culture.

"It's like any other community that never had a road, then got a road, then everything changed," he said.