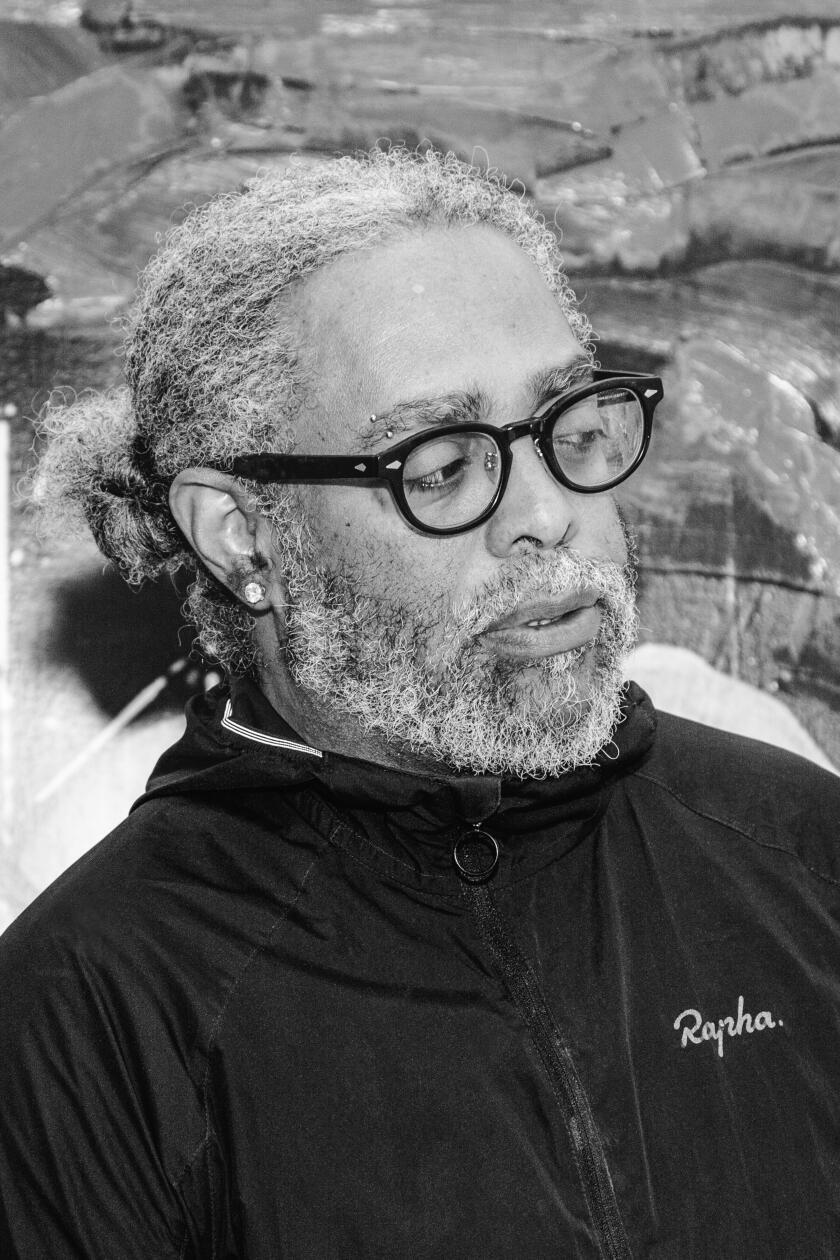

Arthur Jafa shifts into another realm

When I first met Arthur Jafa, Fred Moten was still living in the West Adams area of Los Angeles, and I was living in New York, visiting L.A. for the holidays. Fred invited me and AJ, as friends call him, to dinner, and I remember, because I recorded it, their conversation about Sly Stone recording and then deleting entire albums late into the night at New York’s Electric Lady Studios. I remember this so vividly because it crystallized my sense of the ungovernable collective subconscious of Black life in the U.S. and how evidence of that anarchic mode survives hand to hand, voice to voice and eye to eye. It is rare to find people who care about these stories as if they are the missing minerals in a nutrient-deficient social regime and not scattered tabloids to jut at one another when we don’t feel interesting as discrete subjects. Arthur Jafa, best known as a filmmaker and cinematographer, is possessed by this obsession, this care for missed, uncategorizable, atemporal images and their traces. He shares it the way an arranger shares his manner of hearing a song, as texture and sequence, an etheric demeanor made material.

In February in Los Angeles, AJ and I met to discuss his current work and preoccupations. In an industry where an array of handlers is a marker of having made it, he works alone in his studio, perfecting one of his new endeavors: sound sculptures that feature the altered voices of recognizable performers. Donny Hathaway and Roberta Flack become two men confessing love for one another. The Jackson 5’s “All I Do Is Think About You” is led by Michael Jackson had he been allowed to reveal his post-puberty voice to the world. He sounds like an adult and serious man, and he and his brothers slow down their dance to allow this rite of passage. They spin in unison in two directions at once and the new pace feels natural, like it’s making room for the trouble they all know is coming. They get to grieve in AJ’s fiction. He invents new funerary rites, for bands and individuals. He makes a sonic requiem for Greg Tate. I send a Sun Ra sample in which Ra discusses how seldom Black men are mourned publicly by composers. Greg Tate is the vigilante on the other side of AJ’s timing, his best friend in life and afterlife. Michael is among his most reliable haunts. The myth of Michael was that his father dosed him with hormones to preserve his boyhood vocal pitch. This could be the myth of Blackness itself, that it is never permitted to grow up, to sound too bitter, forever young and inchoate, never atrophying past the dazzling tones of entertainment so that all the world accepts wholeheartedly of Black life is its half-life.

It is rare to find people who care about these stories as if they are the missing minerals in a nutrient-deficient social regime and not scattered tabloids to jut at one another when we don’t feel interesting as discrete subjects.

Harmony Holiday

AJ has two shows coming up in New York this spring, one at Gladstone Gallery and another at 52 Walker. He says of the 52 Walker exhibition that he hopes it will feel like a group show, which is his goal with every solo exhibition: to multiply, proliferate and collaborate with selves present and former and the here-but-gone friends and muses that inflect those selves. He’s also working on a feature-length biopic on blues singer Son House. We discuss the failure of biopics as a form alongside the need or at least rapacious demand for them. What if biopics of Black men and women weren’t so linear and grandiose? What if, like AJ’s films, they sliced and slurred images to get at the contradictory nature of human beings?

Read more: May the ghost of Sun Ra return to lift the 50-year curse he cast on Los Angeles

What we circle back to throughout our conversations is the idea of breakthrough, breaking through, the big break one gets within the context of a chosen industry and how to not let it break you. AJ has been working for more than 30 years, producing, thinking and making, but there was a point at which he broke through, and we wonder together about it in the context of other artists, whose moment came sooner and then they died, or whose moment is overshadowed by legacy or addiction, or who could not see the moment or seize it if it came. He says he’s in a new realm, a new world, with a new frequency, where obscurity can no longer be nursed as a defining characteristic. He’s a known quantity and compelled to show up as many versions of himself as possible.

Harmony Holiday: Do you want to talk about why you were in New York last week?

Arthur Jafa: We can. I was in New York to do a talk at Columbia University as part of the Shawn "Jay-Z" Carter lecture series.

HH: What was the topic?

AJ: I've been doing talks since I was in my mid to late 20s, and I don't see any appreciable difference between when I prepare and when I don’t, so I just don't prepare. I generally literally don't think about it. I actively try not to think about it. To a certain degree, I think that's because I'm not sure if I have very much new to say.

HH: I’m sure you do, you clearly do.

AJ: Well, increasingly it does feel like when I'm doing talks, I'm just sort of repeating myself. I've felt that for at least a few years now.

Most people who know me know that I really like talking, it’s really important to me — not necessarily just public discourse but discourse in general. And when I wasn’t producing nearly as much, I created quite an elaborate discourse around the kinds of things that I was interested in. There was a notion that perhaps my talking about what I wanted to do was, in some ways, getting in the way of doing things. I had a little bit of anxiety about it because I wasn't sure that was the case. I'm not sure that by stopping talking, I'd be any more productive.

I’ve said a few times, my art is hit or miss but my rap is elite. Greg [Tate] used to always say that was my Achilles' heel — once I worked something out in my head, I just didn't necessarily feel that compelled to actually make it.

HH: When you think of someone like John Coltrane, you think of him rehearsing until he bled, his mouth in pain — the pain of constantly practicing and trying to work out a theory with your physical body. Esperanza Spalding once told me that she thought that was an old way of thinking, that it's not that necessary to rehearse that much. It shocked me — I've never heard anything like that, especially from a jazz musician. It was refreshing. As someone who grew up in dance, I’ve always just believed that you were supposed to drill yourself, that the way that you can make something new is by knowing it so well that you improvise on it. Muscle memory allows you to get out of overthinking. That’s how I conceive of your elite rap game, because if you've articulated an idea so much, you have to do something new when you go to enact it.

AJ: For me, it requires a collective effort — one person can’t envision jazz, it just doesn't work. But you can trigger a critical mass, a catalytic context that will mobilize or put the thinking and the practice of individual practitioners into some sort of coherent form.

I think that's important, as an ontological model of cinema. And not just cinema, basically any expressive medium. I'm very interested in what the Black version of things looks like. If you're talking about music, Black music is so developed in some ways, just because we've done so much. But it can almost apply to anything. There were times when I was very interested in what a Black aesthetic in skateboarding looked like. Basketball has Black aesthetics, and jazz does …

If you step into a realm where a Black person has ever operated or Black people have very seldom operated, you transform that realm.

Arthur Jafa

HH: To me, it's some mix of collective improvisation and this will toward sovereignty.

AJ: You can demonstrate the realness of Blackness by demonstrating its capacity to empower or implement itself in these different realms. If you step into a realm where a Black person has ever operated or Black people have very seldom operated, you transform that realm. That, to me, is a demonstration of the realness, the beauty, the power of Black aesthetics. Cinema was such a perfect realm to think through these ideas of what a Black aesthetic manifestation might look like, because it's a realm where our participation has been spotty. When I studied architecture at Howard, I was interested in the same questions. I used to say, if “Kind of Blue” was a house, what would it look like?

HH: I feel like you tap into the elegiac a lot, like your sound piece for Greg Tate. Would you call that elegiac?

AJ: Yes, and requiem. It's also an attempt, on some level, to nominate Greg as an Orisha.

HH: Like a coronation, like nova.

AJ: I always felt like there were producers, and then there were consumers of producers. As much as I dreamed of being a producer, at the end of the day, I was really just a consumer, a very sophisticated consumer. I had a sophisticated sense of what was dope. But outside of a handful of instances, there was no large-scale collective acknowledgment that these moments, these eruptions, were world-class eruptions. “Daughters [of the Dust]” kind of was, but Julie [Dash] directed it; I'm a cameraman on “Daughters.” It made my reputation more than anything, even though I didn't direct it. I just shot it. For a lot of people, it made me a player, but it's kind of like, if Trane had just played on “Kind of Blue,” if he had never done his own records, people might say, "That guy was a hell of a saxophone player," but Trane, sensing his actual capacity, would feel like he had failed.

HH: Well, you don't believe in the binary of birth and death, so how can you believe in the binary of success and failure? That black and white. Do you feel like you were sparing people?

AJ: No, it was more like I was arrested. An ex of mine once said I was like Michael Jordan with a limp — this dichotomy of absolute capacity and very real inability.

HH: That almost makes me think of the trickster archetype, Legba, the god who pretends to have a limp to get you to mirror it, turning on itself.

AJ: You’ve met my business partner, right? Sometimes I tell her I think I'm lazy. I'm just not working as hard as I should be working. She says, "AJ, given how you’re always working, only a workaholic would say you’re not working hard enough." But I do know I procrastinate and hold onto things which are left over from how I was for 30 years. I have more demands on me now, more expectations, and I have more capacity to finish things. But nevertheless, I know I still struggle with procrastination, with doubt, all these kinds of things. It's only been in the last three or four years that I was like, "I think I'm a success." I just think I had blinders on for so long.

Going back to what we were saying earlier, this thing about realms and being in different realms, I often think in the last 10 to 12 years I almost unknowingly shifted into a different realm. It looks very much like the realm I grew up in. But it’s different because when I envision things now, they seem to happen. I'm not thinking harder than I used to, and I don't think I'm working harder. It's almost like you knew these spells, but you knew them in French, and you were in an English-speaking country. You're speaking these spells aloud, and fundamentally, they are powerful spells. But because you're speaking them in French and not in English — as if God is listening in English or French or whatever dictates these things — they're not working. And then, all of a sudden, you inadvertently stepped on a train, and you woke up and God was listening. It's a very peculiar feeling.

HH: Do you feel like maybe you did enough of the spell work with ancestral forces and now you’re being held up?

AJ: It's funny, the other night, as I got out of [my Uber], the driver said something to me. I couldn't hear him and when I got around to the other side of the car he said, "Are you Arthur Jafa?" And he was from Chad. He said he had taught himself how to read English by looking at videotapes of people like Dave Chappelle and me. His name was Rizzo. I think he was listening to our conversation. And he says, "You're very humble." I mean, socially, probably. It's no longer possible for me to uphold this sort of neurotic mechanism I have. It no longer can supersede the objective reality. Sometimes I ask, did I sleep through my moment? If I got a cheat code, did I do everything possible with my code?

HH: Do you think you’re awake in your current moment? Are you motivated to take more risks? Because the sound stuff that you were playing me and the paintings seem brave and new.

AJ: The painting is more like taking a risk just because they generate a whole lot of anxiety. But at the same time, what's the risk? I made six paintings total in 50-some years, they all sold for six figures — what’s the risk?

HH: What’s great from the outside is that it seems like your marker is still whether or not you like something, which makes you effective, more like yourself.

AJ: My aspirations are way higher than what anybody else thinks I’m capable of. My aspirations are: How do you make the s— be on the Hendrix level or Miles level? Or Billie Holiday or Aretha Franklin or James Brown level? Now, whether I'm able to do that or not is seriously in question. But maybe for the first time in my life, I don't feel like it's absurd.

The painting is more like taking a risk just because they generate a whole lot of anxiety.

Arthur Jafa

HH: Can you talk a little bit about what you're doing at 52 Walker?

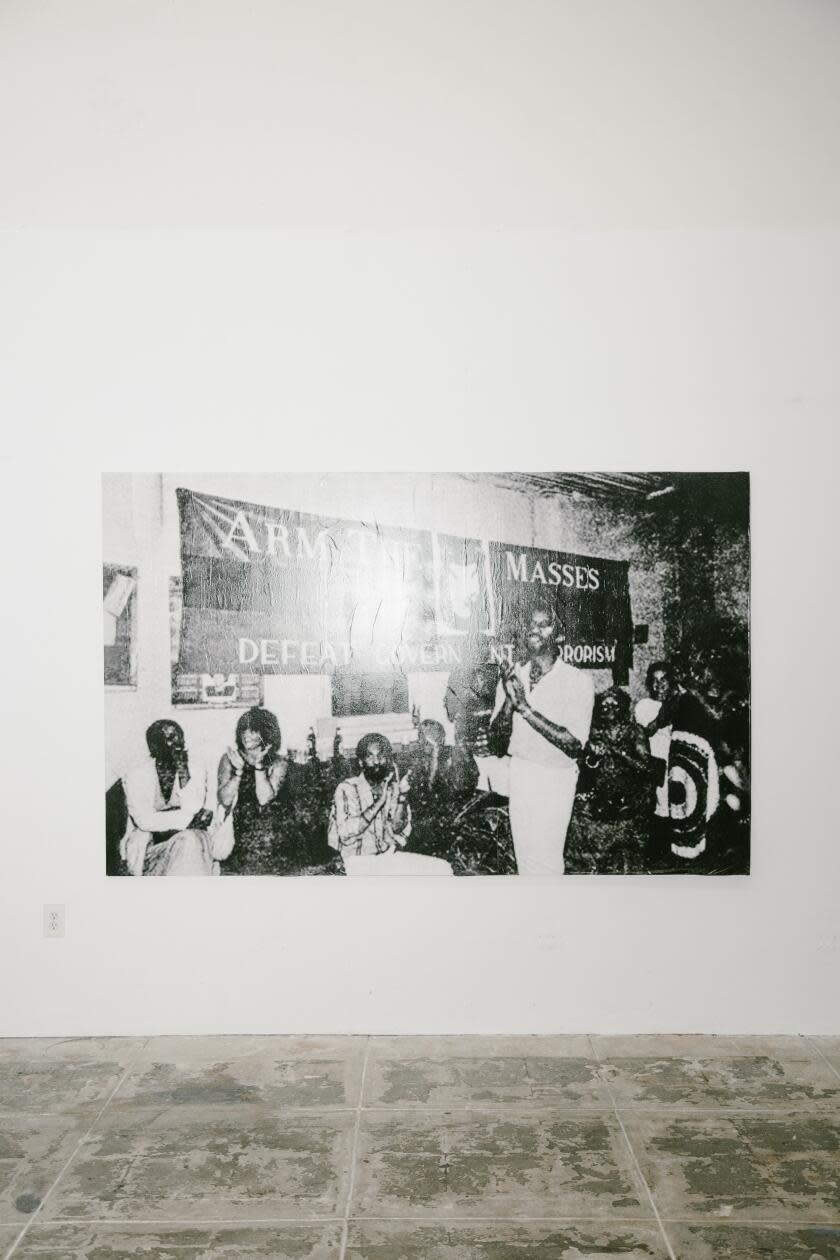

AJ: This specific work is an extension of what I was able to come up with as far back as the Serpentine show in London in 2017. My model for a great solo show is a great group show. I want my solo show to look like the best group show you ever saw — it’s composed of a lot of different things; it's got a lot of variegated artifacts. It's almost like a slave ship, like individuals chained into a boat together. The Middle Passage transforms them to this unified thing.

HH: Duat, the boat that carries the sun in the Egyptian myth.

AJ: Artifacts, physical material artifacts, are something that I'm very, very interested in. And I'm very interested in how to situate and compose and arrange and organize these artifacts, and how you orchestrate the kind of co-occupancy where one artifact inflects another artifact, which inflects two other artifacts. How do you create a chain reaction?

HH: What's the title of the show there?

AJ: “Black Power Tool and Die Trying.” It’s a maze of these different artifacts trying to do that.

HH: To detonate or go off like Jimi or Trane or Michael, but together or in unison this time?

AJ: It has an ensemble dimension. I just want people to have an experience; whether they like it or not is less important as long as they experience something. This show is at the very bleeding edge of my exhibition practice that way.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.