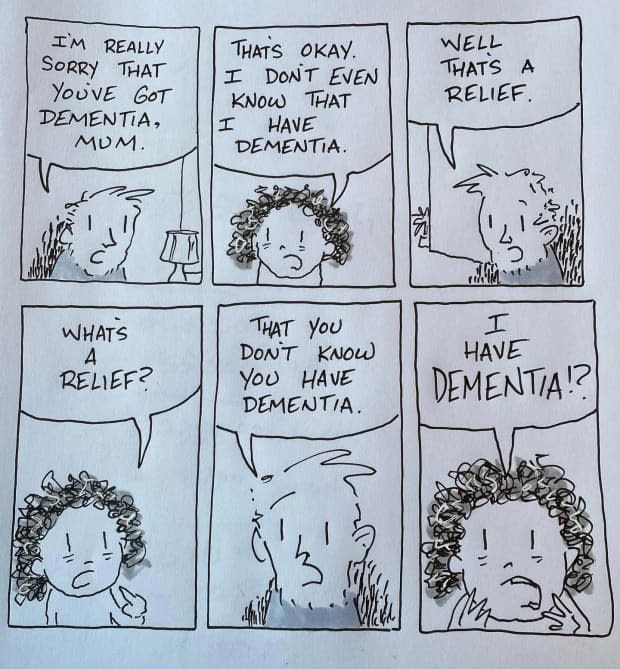

B.C. cartoonist explores the ups and downs of mother's dementia through his art

Cartoonist Gareth Gaudin owns a vintage comic book store in downtown Victoria, B.C. He writes comic books for youth and teaches comics and graphic novels at Camosun College.

He also writes one cartoon every day, sometimes documenting his life, other times making a pun or a joke.

And documenting his life means drawing moments of his mother's dementia.

Here's his story, in his own words, as told to CBC's Gregor Craigie.

Nineteen years ago I started doing a daily comic strip.

As a cartoonist, I felt like I wasn't really capturing enough spontaneity in my life, so I thought I'd do one everyday. There were subplots, like getting engaged and getting married and having kids. These subplots wound their way into my daily project.

Then my mother, my biggest supporter and a good friend and just a cool woman in Victoria, started to show signs of dementia.

I was documenting that as I took her through this kind of adventure. She's doing well, but every time I see her, there's some new thought process worth documenting.

It feels weird because cartoons have a history of being funny or satirical, but I'm trying to capture an honest and sincere approach to the illness.

My mom worked full-time for 60 years as a hairdresser. I started noticing memory loss maybe five years ago.

She came to visit me at my comic store and a few minutes after she left, a skateboarder brought her back — she had fallen on the street and hit her head. She was a bit confused, and I noticed afterward that she started having some memory issues. We started taking note of it.

I took her in for tests and she failed royally. Her reaction to that was she was just joking; she wasn't taking it seriously.

So we took her back for more.

Her driving, that was the thing: she could turn to the left, and see that there were no cars turning to the right — no cars — but she didn't remember.

Oh, was there a car?

It was a constant looking back. That's when we realized we needed to stop that.

It's pretty difficult getting her to change anything in her life. She lived alone, ran her own business, and did everything herself.

But I feel quite lucky — it could have been a lot worse. She could have been angrier, or she could have been less easy to console when she's got depression. I'm feeling pretty lucky with how loving and easily calmed she is currently.

My mom's Scottish. She was born in Dundee and moved to Victoria in 1962. But she still has this broad, Dundonian accent.

My whole life, she always said, "Oh, when I'm doolally I will do this or that."

To her, doolally was having dementia. So when she asked, "Why am I here in this old folks home or why am I not remembering things?'"

"Oh, Mom, you're finally doolally remember?"

And she would laugh it off.

The thing is no matter what we lose about my mom, snippets of our relationship still exists. Even without being able to read the comic strips, she knows she loves me, and she knows she loves that I'm a cartoonist.

So the instant she sees I've drawn a cartoon, she's proud of me. The unconditional support is still there.

My mom and I have the same sense of humour. If she were to read these 20 years ago, she would appreciate them and laugh. I show them to her, but her memory is just two or three minutes, so it dissipates pretty quickly.

The difficult part is knowing where the line is for other people who might be reading them. Many are going through this, and you don't really need a cartoonist seemingly making light of it. But it is an interesting kind of mental state to try to capture on paper.

I wouldn't want to do a caricature of a friend perhaps, for fear they would see it and think, "Oh, what? You highlight me in a weird way."

But with my mom, I can put her in any cartoon and feel confident I'm portraying her with integrity, so it's easier documenting her. If I were a caregiver looking after strangers, I wouldn't want to be crossing that line with them.

Everyone who's commented has been positive. There's a lot of people taking solace in my inky version of dementia. It's helping me. It seems to be helping others as well.

I'm really appreciative of my mom for giving me this kind of line of inquiry. It's helpful to me as an artist.

It's allowing me to approach her in a way, every day, knowing she's still my mom.