Benzodiazepines found in 55 fatal overdoses in July as contamination mounts in B.C.

The memory might be hazy, but Hugh Lampkin says he will never forget the day he unwittingly took benzodiazepine in a desperate attempt to alleviate severe pain in his back.

He thought he was taking heroin, before collapsing head-first onto a steel safe in a back room at the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users headquarters on East Hastings Street.

"I knocked myself out because I fell down and hit my head," said Lampkin, a VANDU board member. "I don't know what I was doing back there, I couldn't tell you."

In the two years since, he's managed to evade drugs tainted with benzodiazepines — but many others haven't.

Percentage of tested drugs with benzodiazepines

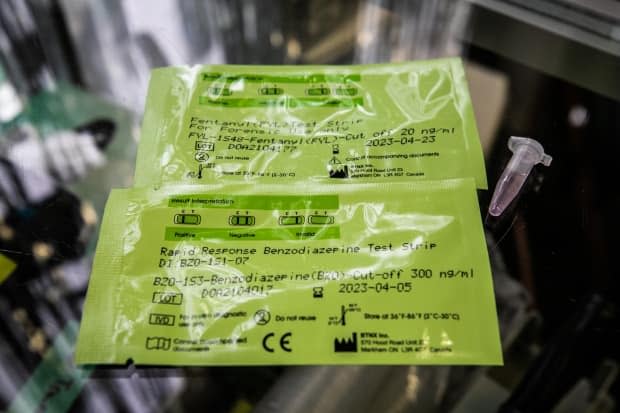

Benzodiazepine, a prescription sedative often used to treat anxiety, is becoming increasingly common in B.C.'s illicit drug market, having been detected in 55 of the 192 fatal overdoses in July, according to the B.C. Coroners Service. Detection rates among all tested drugs jumped from 15 to 52 per cent between January 2020 and January 2022.

The drug can be particularly dangerous when paired with an opioid like fentanyl, because the sedation increases the risk of an overdose, according to Health Canada.

Withdrawal symptoms can include extreme anxiety, sweats and dangerous seizures.

"Those drugs together I suspect have caused a lot of death," said Lampkin.

More unpredictable outcomes

According to Dr. Paxton Bach, co-medical director of the B.C. Centre on Subtance Use, benzodiazepines are being found in as much as 40 per cent of opioids tested provincewide.

"We already know our drug supply is volatile and unpredictable. The amount of fentanyl people are getting exposed to is very variable, and that alone causes enormous amounts of danger," said Bach, who is also an addiction medical specialist at St. Paul's Hospital in Vancouver.

"When you add in other sedatives like benzodiazepines and other psychoactive substances, it makes the outcome that much more unpredictable, and it makes bad outcomes very, very possible and likely," he said.

Along with increased risk of overdose, Bach says it can also lead to significant periods of blackout — sometimes for days at a time — that make people particularly vulnerable to theft, assault, and sexual assault. People exposed to benzodiazepine for longer periods of time can go through withdrawals and experience seizures.

Not easily reversible

Among the most troubling aspects of contamination is what happens once someone overdoses, Bach says.

"The Narcan, the antidote to overdoses, doesn't work on that component of the overdose," he said. "What that leads to is really long overdoses, overdoses where people might end up requiring more Narcan than they need."

Sarah Blyth, executive director of the Overdose Prevention Society, says it's unclear exactly why the prevalence of benzodiazepine-laced opiods, which has become more commonly known as "benzo-dope," has grown over the past two years, but notes it likely has to do with accessibility and profit.

"Sometimes I think it's just easier to get certain drugs than others," she said. "We see all kinds of additives to the drugs, so really it's just a terrible situation and people have just gotten accustomed to putting whatever they want in it.

"Everyone's just trying to make a bit of extra money," she said.

Igniting calls for safe supply

As of July, there have been nearly 1,300 fatal overdoses recorded in B.C. this year, setting a record for the first seven months of a calendar year.

The mounting death toll and prevalence of contaminated drugs continue to ignite calls for improved access to a safer supply of drugs for those in need. Last year, the province announced $22.6 million in funding for health authorities to develop safe supply infrastructure.

"We need to invest in these programs and get them moving faster," said Blyth. "We should just find a way to get a safe drug supply to people who are using drugs who are not going to stop using drugs right now.

"We need to stabilize people's lives."