A Black man died after being restrained by Sacramento police. Now his family seeks justice

Three years have passed since Reginald “Reggie” Payne died after police restrained him in a dangerous position as he suffered a medical emergency, and the grief is still unrelenting.

Payne’s parents have moved out of their South Sacramento home that held the memories of that February 2020 night when a 911 call for a glucose IV turned fatal. They moved to a house in Foothill Farms, but reminders of Payne’s life and death are all over. By the front door, a white poster board with black marker reads “Justice for Reginald Payne Killed by Sac PD.” On a brick mantle is a small shrine of sorts, containing his ashes, a drawing of him, and a “Black Lives Matter” ornament.

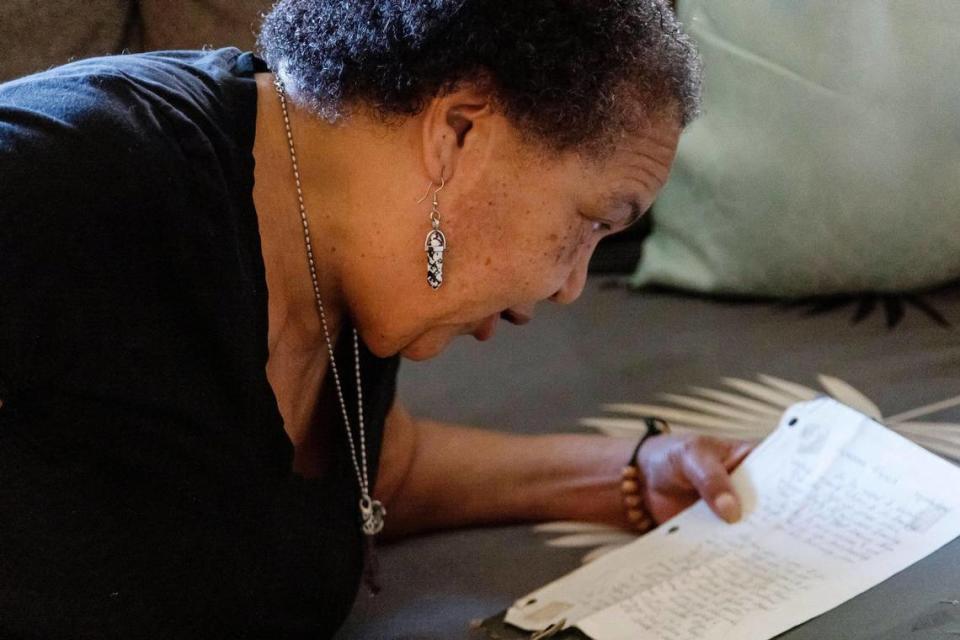

Going through a journal that Payne kept still makes his mother Harriett Jefferson tear up.

On a recent afternoon, she sat on her living room couch and looked at the pages of the journal where her son had written about how much he loves his son, Reggie Jr.

“He was an all around great person,” Harriett Jefferson said. “It makes me so angry.”

In February 2020, Payne, 48, was suffering a medical diabetic emergency and acting erratic, so Harriett Jefferson called 911 to get him an IV. When firefighters arrived at the home, they determined they were unable to treat him, so they called three police officers to restrain him first. The officers held him face down in the prone position, causing him to go into cardiac arrest, ultimately causing his death, according to the coroner’s report.

The close-knit family is bracing to learn later this year whether a fire captain whom the city fired as a result of the death will get his job back. They want the city to also discipline the three police officers who held him face down as he screamed “I can’t breathe.”

‘Like everyone was going to college’

Payne grew up in public housing in Oakland. He attended Stonehurst Elementary where he was in the gifted and talented program, followed by Castlemont High School, Harriett Jefferson said. About 90% of the students at Castlemont are socioeconomically disadvantaged, and only about half graduate, according to state data.

Payne was harassed by police starting as young as age 9, he wrote in a 2018 self-published book. He wrote that he was walking through a park with friends, when a San Leandro police officer falsely accused him of of public urination and drove him home in a police car. He also wrote of a later experience when he came home from college and was working at FedEx, police stopped him and handcuffed him.

“He was always harassed,” Harriett Jefferson said.

He was a popular kid who loved sports, and was the student body president. He had a dream to be a sports writer, and moved to Louisiana to attend Grambling State University, a historically Black university.

“We grew up in the projects in Oakland,” Payne’s younger sister Crystal Jefferson said. “He was the first person to go to college in our community. That meant something to us.”

Payne’s success gave hope to many other kids in the neighborhood that they too could go to a university, even if their parents didn’t, his oldest sister said.

“When Reggie went to college, it was like everyone was going to college,” his sister Janine Jefferson said.

At Grambling, he pursued his dream of becoming a sports writer. He worked for the student newspaper and got a prestigious internship at The Tennessean in Nashville. He graduated and got a job at the San Leandro Times covering sports. But then he suffered a mental health crisis and in 1996 was admitted to John George Psychiatric Hospital in San Leandro. He was never the same when he came out, Crystal Jefferson said, and it derailed his dream to become a professional newspaper journalist.

Payne turned to writing about himself in the book titled “The Harassment of Reginald D. Payne.” In those pages he wondered about the police mistreatment of Black men and his anxiety over what might happen to him.

“I often wonder how many other black men have suffered or been tortured over the years, dead and gone, and no one even knows or knew,” Payne wrote on the fifth page of the book. “Personally one of my worst fears.”

‘He just needed sugar’

In addition to the mental health issues, Payne struggled with diabetes and also kidney issues. In late 2019, Payne was acting “not himself” while experiencing a hypoglycemic episode due to low blood sugar. Harriett Jefferson called 911, Sacramento firefighters administered dextrose through an IV without incident, and Payne was quickly back to normal, she said.

On Feb. 25, 2020, when Payne started acting the same uncharacteristic way after forgetting to eat during a dialysis treatment earlier in the day, Harriett Jefferson again called 911 for the IV.

“I could tell he just needed some sugar,” Harriett Jefferson said.

But this time was drastically different. When the firefighters showed up, Payne sat on the couch and put out his hand to shake one firefighter’s hand, but the firefighter declined, Harriett Jefferson said.

Two of the firefighters later told investigators that Payne exposed himself. Harriett and Rufus Jefferson, who were both present, said that did not happen. While Payne had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder, which sometimes causes psychosis, Payne was not experiencing psychosis that night, Harriett Jefferson said.

“It was nothing to do with bipolar that day,” Harriett Jefferson said. “He had a great day. He just needed sugar.”

Instead of quickly administering the IV like their colleagues did several months earlier, the firefighters decided to call the police to restrain Payne in order to treat him. As they waited outside, Payne’s condition rapidly worsened. When the police came, standing outside to plan their response, one officer referred to Payne as a “big boy.” When the officers entered the home, three of them restrained him face down as he cried out for his parents. He lost consciousness and never woke up.

The coroner’s report says cause of death is “sudden cardiac arrest while being restrained in prone position.”

The city in response fired Fire Capt. Jeffrey Scott Klein, the highest ranking fire employee on the call, for standing by as the police held Payne in the dangerous position, even as he became unresponsive. During the investigation Klein received over $138,849 while on paid leave. Depending on the outcome of his arbitration in July, he may get his job back. The remaining four other firefighters and three police officers kept their jobs. Firefighter Clinton Simons was promoted on May 15.

The city has not yet provided The Sacramento Bee with police disciplinary records in response to a California Public Records Act request. Joseph Nicholson, the family’s attorney, said through his work on the case, he has not seen any evidence to indicate the city disciplined the police officers.

The family members said the city should discipline the police officers.

“They hogtied my brother,” Janine Jefferson said. “Legs and arms shackled together. They did it in the comforts of my parents’ house, while my parents were there. How are they treating people on the streets?”

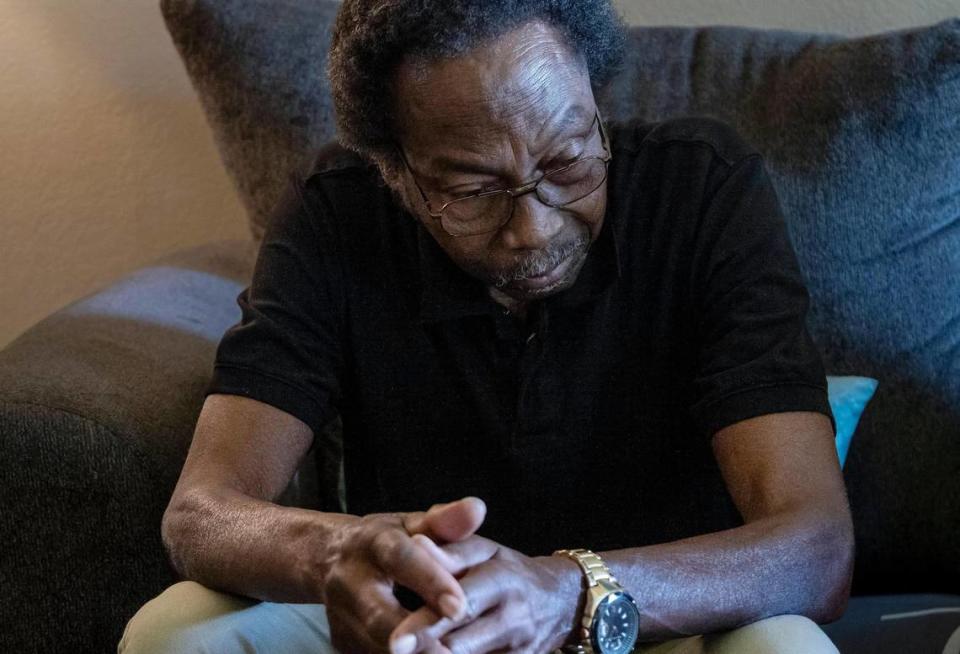

Harriet and Rufus Jefferson in February 2022 filed a wrongful death lawsuit against the city, which is ongoing. Rufus Jefferson was Payne’s stepfather since Payne was 11 months old. In addition to monetary damages, the lawsuit seeks an injunction to require police officers, firefighters and paramedics not to use “improper restraints” such as the prone position in emergency medical situations in the future. It also seeks for the city to require officers to attend racial bias training and create a mechanism to discipline officers who engage in racial discrimination.

The city has declined to comment on the lawsuit because of pending litigation, city spokesman Tim Swanson has said.

The trial is currently scheduled for February 2024.

In the meantime, Payne’s family wants to raise awareness about police brutality and racism so Reggie’s death, though somewhat overshadowed by the coronavirus pandemic, was not in vain.

“Everyone thinks if you do everything the right way, you’ll be great,” Crystal Jefferson said. “The story of Reggie is that you can do everything the right way and still be killed. You can write books, you can go to college, you can do everything to be a good citizen and still die because of your color.”