Black N.B. sprinting star from early 1900s to be honoured at national championships

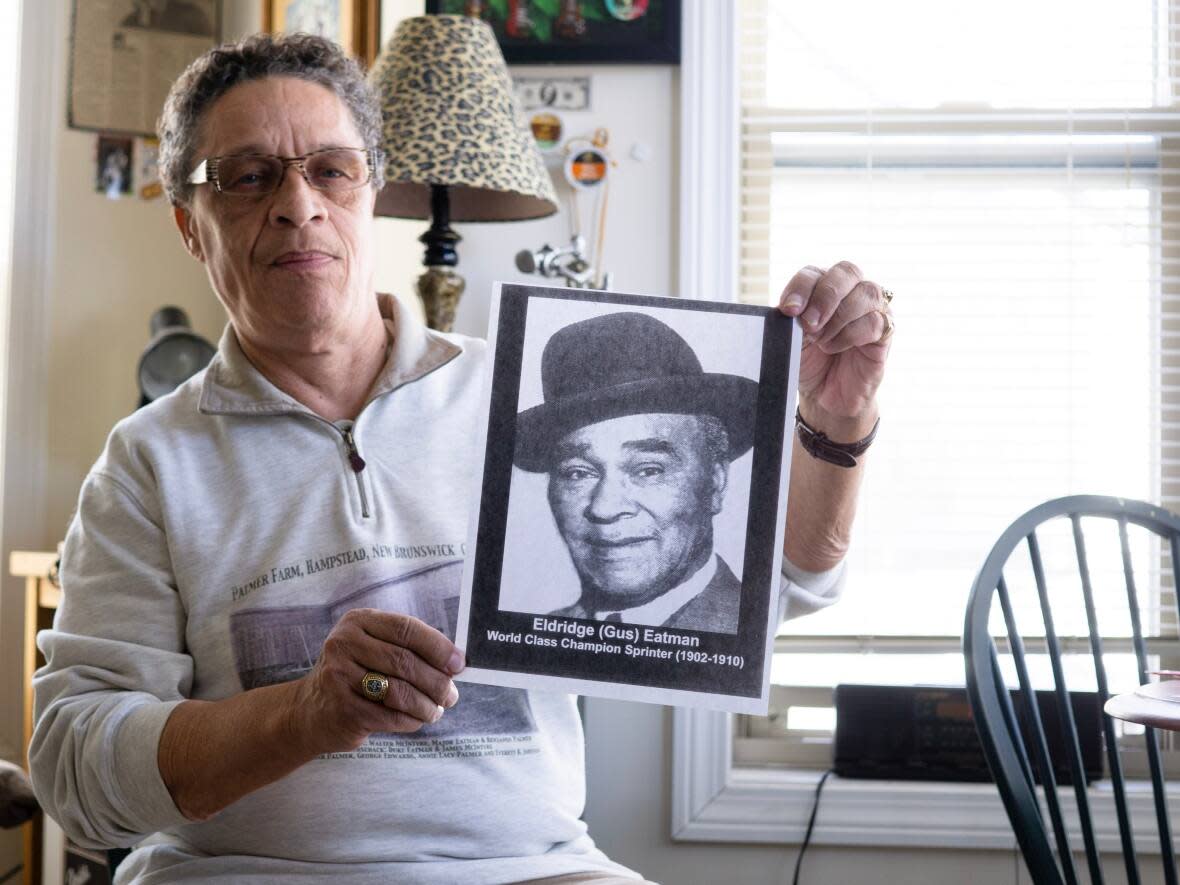

Maurice Eatmon has made it his life's purpose to share the legacy of Eldridge Eatman — a New Brunswick man who set speed records at the turn of the 20th century.

On Saturday, about 20 years of work will pay off when Eatman is honoured at the national level for the first time. There will be a ceremony honouring him at the Canadian Indoor Track & Field Championships in Saint John's Irving Oil Field House, hosted by Athletics Canada and the Saint John Reds Track & Field Club.

"It means the world to me," Maurice said, about the national recognition and ceremony, where a plaque commemorating Eatman's remarkable life will be unveiled in the field house.

Maurice is family — he is Eatman's third cousin, though he spells his last name Eatmon, a variation chosen by his father.

Eldridge Eatman was born in 1880 in Zealand Station, now known simply as Zealand, a small community around 33 kilometres northwest of Fredericton.

By the time he died 80 years later, he held a record as one of the fastest men in the world, had spent 785 days in the trenches of the First World War, and he had raised money to fight Italian dictator Benito Mussolini's invasion of Ethiopia.

And he did so at a time when Black athletes weren't welcome in amateur track and field and few competed professionally.

Bill MacMackin, president of the city's track and field club, has known Maurice for about a decade and has helped him work to get Eatman's importance recognized.

Eatman is in both the Saint John and the New Brunswick sports halls of fame. It was MacMackin who started the process of obtaining national recognition.

"It's an amazing story," said MacMackin. "We just thought it would be something nice to immortalize, particularly here at a national event. And close to the site where he ran."

Who was Eldridge Eatman?

In 1903, Eatman beat the American world champion sprinter Thomas F. Keen in a 120-yard dash at the Moose Path racing track, which was about a hundred yards from where the field house now sits, according to MacMackin.

In 1905, he set a Canadian record when he ran 100 yards in 9.8 seconds — by comparison, Usain Bolt's 100-metre record, which is 109 yards, is 9.58 seconds. And in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1906, Eldridge captured the Powderhall Trophy, essentially the world championship.

But as a Black man in the early 20th century, doing so was not easy.

"The civil rights movements happened in the '60s. He was running in the early turn of the century, so [imagine] how much harder it would have been then," Maurice said.

He said Eatman was treated all right when he won, but when he lost he was subjected to racial slurs.

Maurice said Eatman was as much of a breaker of barriers as Jackie Robinson in baseball or Willie O'Ree in hockey.

And he became friends with other Black athletes, Maurice said, such as Jack Johnson, the American boxer who became the first Black heavyweight champion of the world in 1908.

During the First World War, when Black volunteers in Canada were being turned away from recruitment stations and told it was a white man's war, Eatman joined the British army.

He served with the Royal Northumberland Fusiliers and spent more than two years in the trenches before being wounded in the leg in France.

Years later, he recruited volunteers and raised funds to fight against Benito Mussolini's invasion of Ethiopia in 1935.

Fighting for recognition

Maurice never met Eatman, who died in Saint John in 1960, five years after Maurice was born.

He heard stories about his cousin, but said he didn't really take it in when he was a kid.

"So then I finally did the research on it, found his obituary and everything else, and it says world champion. I said, 'there's more to this than that.'"

Now, after researching his life, Maurice feels he knows Eatman better than he knows himself.

"When you find something new out about him, or whatever it is, it's almost like a spiritual type of thing."