Daily Brew

Daily BrewU.S. expects immunity for its cops working in new cross-border policing program

We've all heard of diplomatic immunity, the international convention that exempts select representatives of foreign countries from arrest and prosecution unless that protection is specifically waived by their government.

The privilege has been occasionally abused, but it's a vital element in allowing diplomats to operate in sometimes hostile environments without fear of being detained.

But how do you feel about foreign cops being given similar immunity while operating in Canada?

That's reportedly what the United States is asking for as part of a cross-border policing agreement with Canada.

The Canadian Press says it has obtained an RCMP briefing memo under access-to-information legislation that details the Mounties' reservations about allowing American officers to work with legal immunity here.

[ Related: Misbehaving diplomats struggle to hide behind immunity in Canada: reports ]

"Canadians would likely have serious concerns with cross-designated officers from the U.S. not being accountable for their actions in Canada," says the classified memo prepared for RCMP Commissioner Bob Paulson, a censored version of which was obtained by CP.

The Conservative government is working on a wide-ranging deal for cross-border law enforcement aimed mainly at reducing the trade bottlenecks at the Canada-U.S. border created after the 9/11 terror attacks.

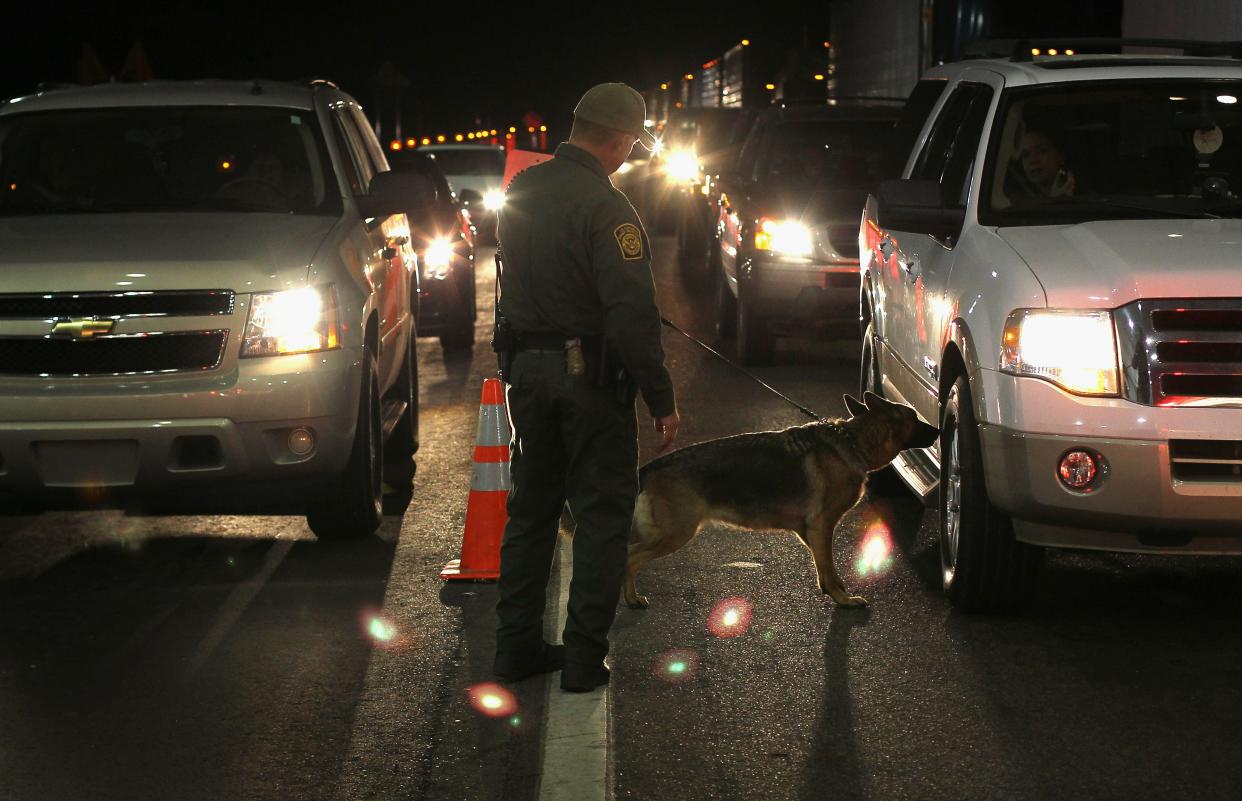

The program initially allows U.S. Customs and Border Protection officers to work with Canada Border Services agents at truck pre-clearance areas on the border, with the first two pilot projects set up at Fort Erie, Ont., and Surrey, B.C.

"In addition, we will implement 'Next Generation' pilot projects to create integrated teams in areas such as intelligence and criminal investigations, and an intelligence-led uniformed presence between ports of entry," says a description of the program on Ottawa's Action Plan web site.

But the October 2012 memo reveals that Canadian and U.S. officials are at odds over whose legal system would apply to the visiting officers, CP said.

According to the RCMP memo, these kinds of cross-border initiatives have operated on the understanding that the laws of the host country apply to illegal acts committed on its territory and that its courts would have jurisdiction, CP reported.

"However, the U.S. has recently expressed concerns with the continued application of the 'host country law model' and has requested that its officers be exempted from the laws or the jurisdiction of the ordinary courts in Canada in the context of the Next Gen and Pre-clearance initiatives," the memo says, according to CP.

Public Safety Canada spokeswoman Josee Picard confirmed to CP that while U.S. customs officers working in Canadian cargo pre-clearance areas would be subject to this country's laws, the issue remains unsettled for the policing component, which was supposed to be running by last year.

This isn't the first instance Americans have insisted its uniformed representatives abroad be swathed in a legal bubble of red, white and blue.

The U.S. military was immune from prosecution by Iraqi authorities during its occupation of the country after the 2003 war. As American forces withdrew, the U.S. government tried to negotiate immunity for private defence contractors working for the State Department, the U.S. Army newspaper Stars and Stripes reported in 2011.

Likewise, U.S. forces in Afghanistan were also not liable to the country's admittedly dubious justice system and talks have been underway to give immunity to American troops remaining after the scheduled 2014 withdrawal of combat units, according to the Associated Press.

[ Related: Cross-border policing provokes sovereignty worries ]

One of the most infamous cases involved former soldier Raymond Davis, a private contractor working for the CIA, who was arrested in Pakistan in 2011 after reportedly killing two armed men who approached his car in the city of Lahore in 2011. A third man was run over. Evidence suggested Davis had been on an espionage mission.

The U.S. asserted that Davis was covered by immunity because he had travelled to Pakistan on a diplomatic passport. Ultimately, he was released after U.S. officials negotiated a US$2.3-million "blood money" settlement with the dead men's relatives under Islamic Sharia law. The incident didn't help America's deteriorating relations with Pakistan.

But Canada isn't Afghanistan or Pakistan. The RCMP memo says there are several reasons why visiting American officers should be subject to Canadian law, including the historic jurisdiction of sovereign states on their own territory, the similarity of the U.S. and Canadian justice systems related to the use of force by police and the fact the cross-border agreement was premised on each country's legal system applying to the program.

It "would not be feasible nor desirable to have two law enforcement officers working together being subjected to different regimes for accountability and criminal liability," the memo says, according to CP.

But the memo concludes by advising Paulson that the Mounties should work to develop options "ensuring that law enforcement concerns are properly addressed, rather than taking a firm stance on retaining the status quo." Canadian police working in the U.S. would have get the same protections, it adds.