Bob Graham, former Florida governor and U.S. senator, dies at 87

Bob Graham, the former Florida governor and U.S. senator who ushered in the state’s era of school-competency testing, crafted the foundation for its modern environmental policies and grappled with the mass influx of Cubans fleeing across the Straits of Florida in the early 1980s, died Tuesday night, according to his family. He was 87.

Graham left his fingerprints throughout the state over his more-than four decades in Florida politics, during which he became known for his pragmatic, centrist approach.

As governor, his 1983 “Save Our Everglades” restoration program served as the foundation for four decades of state and federal efforts to bring back and preserve the natural flow of the River of Grass.

As a senator, he pushed for greater transparency around the terrorist attacks on Sept. 11, 2001, and earned a reputation as a conscientious objector, becoming one of just 23 U.S senators to oppose then-President George W. Bush’s request to authorize the use of force preceding the 2003 Iraq war.

And on the stump, his “work days” — a series of more-than 400 campaign stunts that brought him closer to Floridians by working everyman jobs like garbage-loader, short-order cook and bulletproof-vest maker — created a model for politicians eager to appear blue collar.

“Bob Graham devoted his life to the betterment of the world around him,” his family said in a Tuesday night statement announcing his death. “The memorials to that devotion are everywhere — from the Everglades and other natural treasures he was determined to preserve, to the colleges and universities he championed with his commitment to higher education, to the global understanding he helped to foster through his work with the intelligence community, and so many more.”

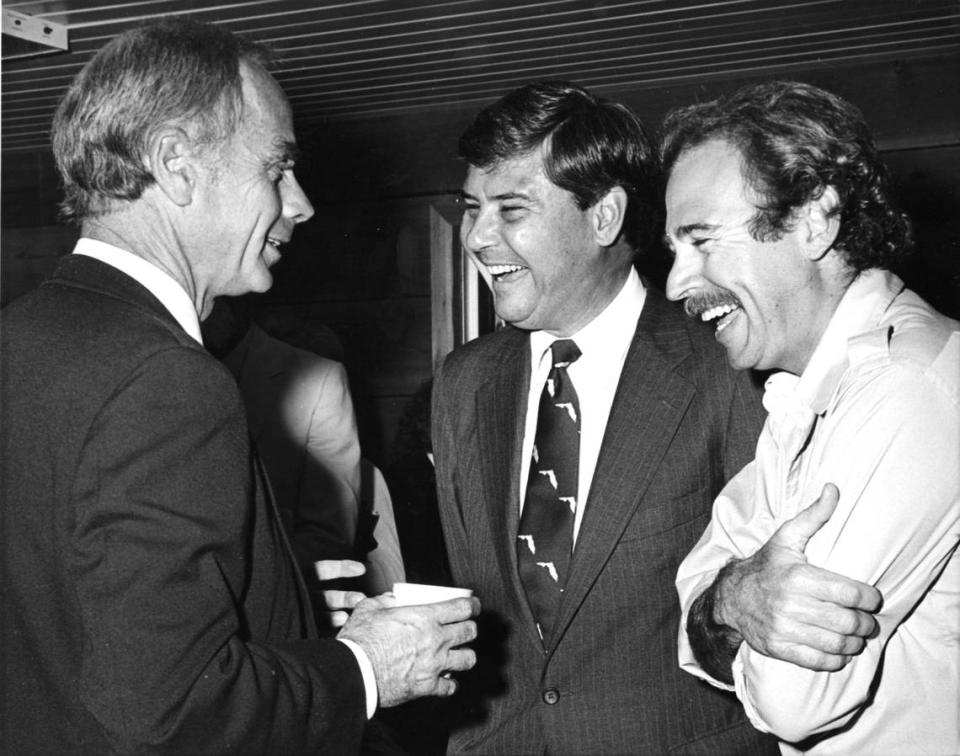

Photo Gallery: ‘Work Days,’ the jobs Bob Graham loved most

Early Life

A vestige of old “Miamuh,” Graham was born Daniel Robert Graham on Nov. 9, 1936, in Coral Gables to Hilda Simmons, a schoolteacher, and Ernest “Cap” Graham, a Florida state senator and sugar cane and dairy farmer. Graham was the youngest of four children in an influential family.

His oldest brother, Philip Graham, would become publisher of The Washington Post in 1946, a title he held until his death in 1963. Another of Graham’s brothers, William Graham, became president of The Graham Companies, which developed the town of Miami Lakes beginning in the early 1960s.

Bob Graham attended Miami Senior High School in the 1950s, and was student body president his senior year. He went on to graduate with a bachelors in political science from the University of Florida in 1959, the same year he married Adele Khoury, of Miami Shores, with whom he had four daughters: former Congresswoman Gwen Graham, Cissy Graham McCullough, Suzanne Graham Gibson and Kendall Graham Elias. They, in turn, gave him grandkids.

“Bob Graham would tell people his favorite title was not Governor or Senator. It was the name his grandchildren gave him: Doodle. ’When I’m really good, they call me Super Doodle,’ he liked to say,” his family wrote Tuesday night. “For 87 years, Bob Graham was so much more than really good. He was a rare collection of public accomplishments and personal traits that combined to make him unforgettable.”

After earning a law degree from Harvard University in 1962, Graham entered politics. He was elected to the Florida House of Representatives in 1966 at the age of 29, and re-elected in 1968 before jumping to the Florida Senate in 1970. He served three terms in the upper chamber, representing District 33, which included portions of southwest Broward County and northwest Miami-Dade.

As a lawmaker with pedigree — assisted by the connections his older brother made while advising President John F. Kennedy and publishing The Washington Post — Graham authored legislation requiring testing for competency and progress in schools, and began passing legislation to clean up Florida’s environment, which until then had not been a priority for the Florida Legislature.

Graham was something of an ideologue, and part of a group known as the “Doghouse Democrats,” a more progressive clique at odds with the Florida Panhandle establishment. He also placed himself under pressure to succeed. Jack Gordon, a Miami Beach banker who served in the Senate with Graham, told the Orlando Sentinel in 2003 that, when Graham told him on a flight home from Tallahassee that he would run for governor, he put it like this: “I’ll be 40 next year, and I really have to do something.”

Work Days

In 1974, when Graham was chairman of the Senate Education Committee, a group of high school students altered his life and political trajectory when they came to a hearing in Jacksonville to complain about the food at school.

“What I was surprised about was that they had come to the state Senate to try to seek relief,” Graham recalled during a 2009 interview with the Miami Herald. “I asked them if we were the first people they’d talked to, and they said no, they’d also talked to the mayor of Jacksonville and the sheriff of Duval County, and neither of them said they could give them any help.”

— Gwen Graham (@GwenGraham) April 17, 2024

Graham shared the story with a group of civics teachers a few weeks later, calling it “an indication that something was wrong with our teaching of civics if high school seniors thought that the mayor and the sheriff and the state Legislature controlled the greasy pizzas in their cafeteria.” As the story goes, his take grated on one of the teachers, a friend of Graham’s, who got up and angrily told Graham she was tired of clueless politicians “telling teachers how to do their work.”

“I ended up teaching 18 weeks of civics at Carol City Senior High School” in Miami-Dade County, Graham later told the Herald. “It was a life-transforming event. I learned about the reality of a big high school, the students, teachers, parents, administrators. I also, maybe more importantly, learned the value and the importance of learning by doing, as opposed to learning by reading about it or of having someone give you a lecture.”

The experiment became a staple of Graham’s political persona, as he kicked off a series of “work days” that included stints chopping down home-grown marijuana plants with a machete, hanging 600-pound glass panels at a Duval County construction site, working as a “grip” on the set of a Burt Reynolds movie, and even bringing delight to children as a mall Santa Claus. During one 1978 campaign work day as a bellhop at Orlando’s Sheraton Twin Towers, he ended up delivering a bag to the penthouse suite of his opponent, the Democratic primary front-runner for governor, then-Attorney General Bob Shevin.

Graham, a multi-millionaire, would do 100 work days during his first campaign for governor, and 408 total over 30 years.

“His workdays are an extension of his belief in a personal style of governing,” Graham’s U.S. senate colleagues wrote in a farewell address read onto the Senate floor when Graham retired. “By working closely with Floridians, Graham learned about the hopes and challenges they face. For him, there was no substitute for that kind of on-the-job experience.”

Governor Graham

The gimmick helped Graham — whose father had run unsuccessfully for governor 34 years earlier — win the 1978 governor’s race. His campaign included a fight song: “Bob Graham is a cracker. Be a Graham cracker backer.” Graham was known for singing at campaign rallies.

During his eight years as governor — he was reelected in 1982 with 64% of the vote — Graham developed a reputation for late hours, early morning staff calls, and a preference for hard work over back-slapping. He ran habitually late for meetings and appointments due to long conversations, though his disinterest in chit chat also led some to incorrectly believe he was aloof.

And yet, Graham — whose transformation from intellectual to “ordinary guy” might be exemplified by his decision to move away from the name D. Robert Graham to just Bob — could also be flamboyant and self-deprecating.

In 1986, during the annual Tallahassee press skits — playful hazing among Capitol reporters that often included a “rebuttal” from the governor — Graham arrived in full military garb, backed by the Florida A&M Marching 100, to declare himself “governor for life.” Another year, Graham showed up with the late crooner Jimmy Buffett, a friend, and they sang a version of the singer’s “Margaritaville” that they called “Wasting Away in Tallahassee.”

By that time, Graham had won over fans and critics alike, with most detractors begrudgingly acknowledging his successes.

Still, Graham’s first year as governor was seen as slow and his ambition so broad as to be somewhat aimless, earning him the nickname “Governor Jello.” And he faced intense challenges.

He was governor of Florida in April of 1980 when then-Cuban dictator Fidel Castro — reacting to thousands of Cubans seeking refuge at the Peruvian embassy on the communist island — opened the floodgates for masses of Cuban and Haitian refugees who wanted to escape. An estimated 125,000 Cubans, many aboard makeshift vessels, some released from prisons and mental health institutions, made the 90-mile trek across the Florida Straits, catching the Jimmy Carter administration off-guard.

Robert McKnight, at the time a state senator representing Miami-Dade and the Florida Keys, recalled in a 2018 Op-Ed that on April 20, when the first of hundreds of boats began arriving in Key West, an aide to Graham fetched him in Tallahassee to join Graham in the governor’s office at the state Capitol. McKnight said that when he and his wife arrived, they found the governor, his staff and a Key West state representative shouting, with then-Miami Congressman Dante Fascell, chairman of the House Foreign Relations Committee, who was on a speaker phone.

“Televisions were on in Graham’s office. ABC, CBS and NBC all had live coverage of Havana, the Straits, Key West and Miami. Helicopters had television crews on board recording thousands of small boats making the dangerous trip in perilous seas, with dozens of distraught Cubans hanging onto the boats,” McKnight recalled. “Fascell said President Carter was awaiting Florida’s recommendation for action by the United States.”

The mass migration, which Castro announced without warning, created a humanitarian crisis in South Florida, racial tensions, and worries of a crime wave like the one depicted in Brian de Palma’s iconic movie, “Scarface,” featuring actor Al Pacino as a Cuban cocaine king pin — a film Graham would later push to keep in Miami as filmmakers faced resistance over the content of the movie. Graham declared a state of emergency on April 28.

Over the coming years, Graham would spar with the administrations of Jimmy Carter and later Ronald Reagan, arguing that the federal government had abdicated its responsibility to address a federal immigration crisis playing out in the state of Florida.

Graham, in a foreword he wrote for the book, “Florida and the Mariel Boatlift: The first 20 Days,” said Castro’s sudden decision to open the floodgates came at a particularly vulnerable time for the United States and for South Florida. Carter, whom Graham supported and would go on to nominate later that year for reelection at the 1980 Democratic National Convention, was wounded by the Iranian hostage crisis and a bungled hostage rescue mission that had just led his secretary of state to resign. And Miami-Dade County, Graham wrote, was “still reeling from floods, fuel and water shortages, and the aftermath of Hurricane David.” But due to Carter’s preoccupation, the state and local governments shouldered the burden of the crisis.

Graham dealt with other crises as governor, including a 1979 truckers’ strike that forced the governor to call out the National Guard.

Graham, a Congregationalist, also signed multiple death warrants as governor, earning him the nicknames “Bloody Bob” and “Governor Death.” Graham set a record during his second term for death warrants signed during a Florida governor’s term with 15, which stood until former Gov. Rick Scott topped it. The number of prisoners executed by Graham has been a point of contention for critics, who speculate that Graham escalated the pace during election years. Less noted, however, is that Graham refused to sign 20 death warrants.

He also left an overcrowded prison system behind that forced his successor, Bob Martinez, to ease the burden by freeing thousands of prisoners.

Senator Graham

In 1986, facing term limits, he ran for the U.S. Senate, defeating Republican incumbent Senator Paula Hawkins. Graham would go on to win reelection in 1992 and again in 1998, each time by overwhelming margins. In his third and final reelection campaign against then-Republican Charlie Crist, Graham won by 25 percentage points.

As a senator, Graham came to embody the pragmatist, centrist wing of the Democratic Party while taking on a number of important tasks. He spent a decade on the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, a bully pulpit that he used to pressure the U.S. government to release more information about the 9/11 terrorist attacks, particularly as it pertained to the involvement of a Saudi family living in Sarasota. After retiring, he served as co-chair on the National Commission on the 2010 British Petroleum Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill in the Gulf of Mexico.

In 2004, Graham published “Intelligence Matters: The CIA, the FBI, Saudi Arabia and the Failure of America’s War on Terror,” one of multiple books he authored. The most recent: “Rhoda the Alligator,” a children’s book published in 2020.

Ahead of the 2004 election, Graham launched an exploratory bid to run for president, a post people around him believed he’d always coveted, dating back to his time as governor. He’d already been considered as a likely running mate in repeated presidential cycles, ending up on Bill Clinton’s shortlist in 1992 before Clinton settled on Al Gore. But Graham’s campaign faltered after he had open heart surgery in January 2003 and he withdrew his candidacy at the end of the year, before getting to the Iowa caucuses.

Upon retiring from the Senate in January 2005, Graham had served 38 consecutive years in public office.

He never lost an election.

Herald/Times Tallahassee Bureau staff writer Alexandra Glorioso contributed to this report.