'Brilliant': Artificial gravity isn't just science fiction

This story is part of Moon Landing: 50th Anniversary, a series from CBC News examining how far we've come since the first humans landed on the moon.

In what sounds like something straight out of science fiction, researchers are testing out a form of artificial gravity to counter the physiological hazards of weightlessness astronauts experience in space.

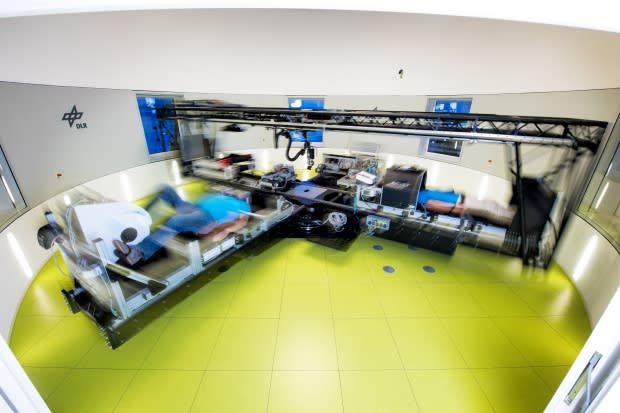

At a research facility in Cologne, Germany, scientists employ the physics of centrifugation (spinning) to create an effect similar to gravitational pull by putting test volunteers in a large rotating apparatus while they exercise.

The concept is not far off from the iconic scene from Stanley Kubrick's film 2001: A Space Odyssey in which an astronaut is depicted running in what seems like a giant live-in hamster wheel. In reality, the testing device resembles any number of amusement park rides that spin.

Dr. Guy Trudel said the spinning effect is supposed to reverse what happens to astronauts' blood circulation in space, where "most of your blood and your fluids go up to your chest and into your head."

The Ottawa physician is conducting research at the Cologne facility, Envihab, along with scientists from German, European and U.S. space agencies. Trudel's work focuses on the adverse effects of low gravity on bone marrow, which includes an enlarging of fat cells and changes to blood cell production.

"If you don't have white blood cells, you cannot defend yourself against infection. Your immune system will not be functioning. So that's the extreme," he said.

To get around the problem of testing artificial gravity on Earth, paid volunteers first undergo months of lying in bed with their feet elevated to simulate the effects of weightlessness on their bodies, before they exercise on their backs in the centrifuge.

Trudel said most astronauts don't spend longer than six months in space, so it's difficult to study how much longer periods in low gravity might affect them.

He said the centrifuge research could result in a type of rotating spacecraft or at least a module within the vessel that spins in the opposite direction of travel.

"We need to build up a bit more knowledge before we can send people to Mars. We do not know if the damage [to astronauts] will continue to progress at the same rate or if there's going to be a plateau at one point," he said.

NASA and its partners are actively planning for a mission to the red planet in the 2030s.

Aging in hyperspeed

A specialized research facility in Waterloo, Ont., has identified another potentially hazardous effect of weightlessness — the hardening of arteries normally seen in elderly people.

"It's a really advanced aging-like process," said lead researcher, Prof. Richard Hughson.

His team at the University of Waterloo's joint Research Institute for Aging has worked with Canadian astronauts while they're aboard the International Space Station, monitoring their arteries and circulatory system in real time.

Their research attempts to apply what they learn from physiological changes in astronauts on older adults on Earth.

"In six months in space, the arteries get stiffer by the equivalent of about 20 years of aging," he added.

Hughson's new project on vascular aging examines how astronauts develop insulin resistance while in a weightless environment.

The loss of muscle mass is the most noticeable and immediately debilitating damage caused by low gravity observed in astronauts returning from the International Space Station. It can take them months of physiotherapy to regain their preflight strength, despite exercising daily while in space.

Astronaut Bob Thirsk, who holds the Canadian record for most time spent in space, recalled making a concerted effort to build up his strength while aboard the International Space Station in anticipation of returning to Earth and its gravitational pull in November 2009.

The engineers roll their eyes whenever we bring up the topic of artificial gravity. - Astronaut Bob Thrisk

"But I felt like a wet dish rag on landing day," he told CBC News.

As a fan of 2001: A Space Odyssey, Thirsk called the centrifuge as a form of artificial gravity, "brilliant." However, he's skeptical such a device will be built anytime soon. "I don't think we're gonna see a spacecraft like that in our in our lifetime.

"As a medical doctor, I'm a big proponent," he added. "But the engineers roll their eyes whenever we bring up the topic of artificial gravity."

The cost of building such a spacecraft has long been considered prohibitive.

Gravity researcher Trudel agreed the question of feasibility is out of his hands.

"So this is the part that we scientists and doctors are doing. Then we'll pass the information to the engineers to see if that is going to be part of the design of the next spacecraft," he said.

Still, he's optimistic. "I understand that you start from scratch when you plan a new mission and that anything can be built."

Artificial gravity also doesn't address other potential health problems associated with extended space travel such as solar radiation as well as the cognitive and psychological effects of longer missions.