California lawmakers say marine sanctuary shouldn’t be shrunk to cater to offshore wind

The United States’ newest marine sanctuary shouldn’t be shrunk to cater to offshore wind energy development, wrote two U.S. representatives in a letter to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration on Monday.

Instead, NOAA should include the entirety of California’s Central Coast in the Chumash Heritage National Marine Sanctuary, according to the letter by Congressman Salud Carbajal, D- Santa Barbara, and Julia Brownley, D-Thousand Oaks.

The representatives advocated for NOAA to extend the northern boundary of the proposed marine sanctuary to abut the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary and also include a portion of the Gaviota Coast in Santa Barbara County.

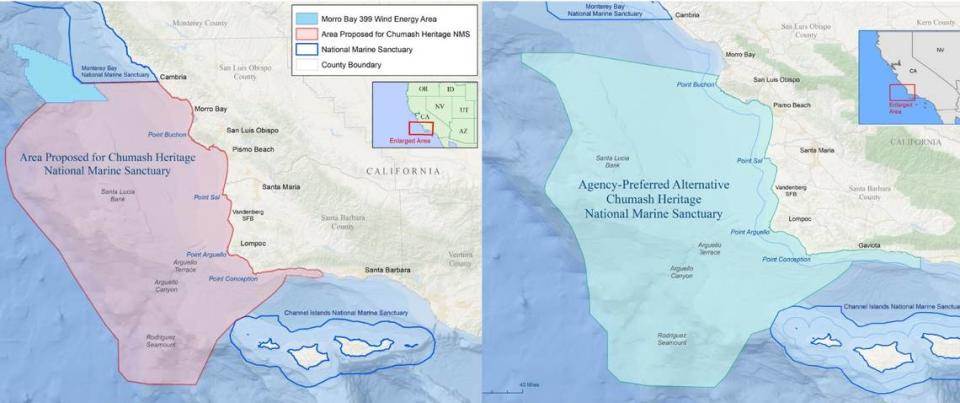

NOAA’s proposal, released in August, left out a 30-mile section of coastline of the originally proposed marine sanctuary that extended from Hazard Canyon Reef south of Morro Bay to the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary boundary at Cambria.

The reason: to assuage offshore wind energy company fears that laying cables from their potential developments could be too complicated to do through a national marine sanctuary.

“Growing our blue economy and being good stewards of our natural resources are not mutually exclusive,” the lawmakers wrote in their letter to NOAA. “We believe that carefully planned and sited offshore wind development can be compatible with environmental protection.”

Marine sanctuary would protect CA’s biologically diverse coastline

Including San Luis Obispo County’s northern coast in the marine sanctuary would protect a stretch of coastline considered to be one of the most biologically diverse and ecologically productive regions in the world, according to the National Marine Sanctuary Foundation.

Extending the marine sanctuary’s boundary northward would ensure it also encompasses underwater Indigenous cultural and historical sites, as well as 40 known historic shipwrecks, the lawmakers’ letter said.

As currently proposed, the marine sanctuary would encompass more than 5,600 square miles off California’s Central Coast.

With the 30-mile section along San Luis Obispo County’s coast included, the sanctuary would cover roughly 7,600 square miles of the Pacific Ocean.

National marine sanctuary status protects an area from most types of development, including offshore oil drilling and sea floor disturbance.

Offshore wind energy development could cause ocean disturbance too great for marine sanctuary

NOAA’s proposed regulations for the Chumash Heritage National Marine Sanctuary include a permit process that could allow for the placement and maintenance of offshore wind sub-sea transmission cables.

However, “the disturbance of submerged lands and associated potential impacts on biological resources that could result from development on this scale would likely be unprecedented in a national marine sanctuary,” NOAA wrote in its proposal for the marine sanctuary.

The offshore wind energy development has been proposed to encompass 376 square miles of the Pacific Ocean about 20 miles off the coast of Cambria and San Simeon. The area was leased to three companies — Equinor, Invenergy and Golden State Wind — in a December 2022 auction for a collective $425.6 million.

By excluding the 30-mile stretch of San Luis Obispo County’s northern coast, “NOAA anticipates developers will be able to plan infrastructure for this area, which may minimize the potential requests to use other parts of the proposed sanctuary,” the agency’s proposal said.

Indigenous leaders also proposed larger marine sanctuary

NOAA’s proposal made Indigenous advocates nervous.

“If what they are proposing is so destructive it can’t be in a marine sanctuary, then should it even happen?” asked Violet Sage Walker in a September interview with The Tribune.

Walker is the chairperson of the Northern Chumash Tribal Council and her father, Fred Collins, was the lead on nominating the marine sanctuary for NOAA’s consideration in 2015. The Northern Chumash Tribal Council has historically supported the proposed offshore wind energy development, Walker noted.

Walker’s comments were echoed by Michael Khus-Zarate, board member of the Coastal Band of the Chumash Nation, which has also historically supported offshore wind energy development.

“But we don’t want other forms of destructive development,” he said in a September interview with The Tribune. “By leaving this corridor open, NOAA is leaving it open for development.”

Representatives Carbajal and Brownley wrote in their letter that there should be a clear permitting pathway for the offshore wind energy companies to lay cables.

NOAA’s regulations for the Chumash Heritage National Marine Sanctuary should “clarify that transmission cables needed for future offshore wind development may be permitted within the sanctuary and to continue to be inclusive in engaging all stakeholders,” the letter said.

“We specifically urge you to ensure that the Chumash Heritage National Marine Sanctuary serves as a model of co-stewardship with the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians and advisory panel engagement with others that identify with indigenous culture,” the letter said.

NOAA is still working on the final designation documents, according to Paul Michel, the regional policy coordinator for the NOAA Sanctuaries West Coast Region.

“They will have to go through a series of reviews and approvals,” he wrote in an email to The Tribune.

The final designation documents should be released in mid 2024, Michel added.