In California, a Native woman’s killing remains unsolved. There are many others like her.

ABOUT THIS SERIES: "A Crisis Ignored" focuses on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, a grassroots movement to draw attention to disproportionate levels of violence against Indigenous people, particularly women and children. USA TODAY Network reporters in nearly a dozen states worked for more than a year to examine the factors that contribute to the crisis and how laws enacted in many states and at the federal level have largely failed to address it.

The body was found inside an abandoned refrigerator, just off a secluded highway that weaves through a forested swath of Northern California.

The remains were small in size and badly burned. There wasn’t much to collect in the way of evidence, save for a lone charm bracelet, some of its little white beads missing, discovered near the charred bones. It read “WWJD.” What would Jesus do?

One year went by, then two. The body remained anonymous. In 2015, after relatives came forward with concerns and an official missing persons report, a DNA sample finally matched: It was 23-year-old Rachel Sloan, a descendant of the Cahto Tribe of the Laytonville Rancheria. A coroner’s report confirmed her cause of death was a gunshot wound to the head.

Nearly a decade after her death, the question of who killed Rachel is unanswered. But her family has tried hard to remember her as she was.

“I feel a strong commitment to Rachel and to find her justice,” said Tasheena Sloan, Rachel’s cousin and vice chairwoman of the Cahto tribe. “And by not talking about her, we're forgetting her.”

Rachel is far from the only Native American woman whose death has been met with silence, or a lack of justice. Her home of Mendocino County alone has seen nine other cases of missing or killed Indigenous women over the past 10 years, according to the data-collecting organization Sovereign Bodies Institute. And that number doesn’t include Rachel’s mother, Deborah Sloan, who was not Native but was murdered in the late 1990s.

Across California, in a tally by Sovereign Bodies, more than 190 Native women or girls have gone missing or have been killed since 1900, making it the state with the fifth highest total number of cases. If Northern California were its own state, it would rank in the top 10 with 112 of those cases. Sovereign Bodies’ figures also include “two-spirit” people, an Indigenous term for those who identify as having both a masculine and feminine spirit.

“It all makes you pretty vulnerable. Young Native women are going missing,” Tasheena said. “I have a daughter. I have little cousins. How can I prevent that? What do we need to do to make this not happen anymore?”

A troubled, complicated history

Around the country, thousands of Indigenous women go missing and are murdered at disproportionately high rates compared with other ethnic groups.

The FBI’s National Crime Information Center reported 5,203 missing Indigenous females in 2021, disappearing at a rate equal to more than two and a half times their estimated share of the U.S. population, which hovers at about 0.7%. The real rate of missing Native women is likely higher; that total was deemed an undercount in an October report to Congress due to a lack of comprehensive federal data.

Because of that dearth of complete data, many rely on statistics from organizations like Sovereign Bodies, though The Desert Sun and USA TODAY do not have access to the nonprofit’s raw data or have details about each individual case included in their tallies.

The fact is, nobody knows exactly how many Indigenous women have been killed or have disappeared, but it’s enough to have its own acronym: MMIW. Enough for President Joe Biden to describe it as an “epidemic,” and for Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland to label it a crisis and call for more federal action. Haaland, the first Native American to oversee the Interior Department that includes the Bureau of Indian Affairs, announced the creation of a new unit to investigate MMIW cases in 2021.

But to understand the modern-day complexities of MMIW, history is crucial.

The state of California plays a role in the long, dark legacy of the subjugation of Native people in the United States. One prominent state law from 1850 facilitated the removal of Native Americans from their lands and allowed for the practice of “apprenticing,” or indenturing, Native children and adults to white citizens. Throughout the country in the 19th and 20th centuries, Indigenous children were taken from their homes to government boarding schools, where the goal was forced assimilation into English-speaking culture. And up until the 1970s, thousands of Native women were sterilized by the Indian Health Service, an agency within the Department of Health and Human Services, without their full consent or knowledge.

As it relates to the handling of MMIW cases, Public Law 280 was enacted in California and several other states in 1953. That legislation gave the states shared authority with tribes to prosecute most crimes on reservations, essentially expanding state criminal jurisdiction while limiting federal powers. The law has often contributed to confusion over who, exactly, should step in after a certain crime takes place and when.

Given those centuries of brutal history, and the laws and policies that have sometimes directly hurt Native people, California Assemblymember James Ramos said it’s no wonder that coordination between the state, tribal governments and local law enforcement has been lacking since PL-280 rolled around.

There hasn’t been a strong enough relationship between those entities when it comes to issues of public safety, he said.

“There’s not only missing and murdered Indigenous persons, but assaults, domestic violence — all these things continue to happen in Indian Country without being reported to law enforcement, because of the feeling that part of the reservation, or the reservation itself, is not included in the judicial system,” he said. Ramos is Cahuilla and Serrano and lives on the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians’ reservation in San Bernardino County. “We have to break that stigma.”

Recent legislation authored by Ramos, AB 3099, puts the issue of MMIW in its crosshairs. Under the new law, passed in 2020, the California Department of Justice will provide training to local law enforcement and tribes, hire for three new MMIW-specific positions within the agency and conduct a study on the topic.

But getting even stronger legislation of that kind through the door is often difficult, Ramos said, because it relies on supporting data that is either incomplete or doesn’t exist, a pervasive problem for Native communities with issues like MMIW, census counts and even COVID-19 death rates.

“This has been happening in Indian Country for years. It's not something new,” Ramos said of MMIW. “It's just now that it's reaching the advocacy and the awareness level of those outside of Indian Country.”

‘Where’s Rachel?’

Rachel Sloan spent a big part of her short life on the Laytonville Rancheria, a small, boxy plot of tribal land about three hours north of Sacramento. To the west, the Pacific Ocean is a 45-minute drive through wooded and rural country; to the east, the Mendocino National Forest features even more remote territory.

Rachel’s grandmother, Pauline Sanderson, remembers her as a good student from a young age, with dreams of becoming an oceanographer one day; “The teachers all liked her because she did her work,” she said. Her younger brother remembers her as a bulldog of an older sister, someone who would stick up for him if need be.

“She’d say she was gonna kick somebody's ass if they were messing with me,” Jacob Sanderson said. “She was always protective of me, was always there for me, you know?”

Rachel also had a mind of her own. As she got older, she would sometimes take off for days at a time, hitching rides with strangers, without telling anyone where she was going. She was generally a wanderer, but would always come back.

“She did what she wanted to do, she wasn't afraid,” Tasheena, her cousin, said. “We would always say, ‘You don't get scared hitchhiking?’”

The answer was no. “She had the softest little voice and she would laugh,” Tasheena said. The two were about five years apart in age and lived across the reservation from each other.

But Rachel and her two brothers also had to contend with the emotional aftermath of losing their mother Deborah, who was strangled to death in 1998. An acquaintance, John Annibel, was convicted of her murder and sentenced to 25 to life (he remains in a California prison today). On the day of Deborah’s death, the two had met at a now-shuttered local bar in Laytonville before heading to a nearby motel together, according to police reports. Deborah’s body was found two days later, down an embankment, by a road crew that had been checking the area for storm damage.

Their mother’s death, Jacob said, inevitably had a “big impact” on Rachel, who was just 8 or 9 years old.

For Rachel, things started to fall apart after high school. She battled waves of persistent mental health issues and delved deeper into drugs. She was arrested twice in 2012 on charges related to possession and being under the influence of meth, according to Lt. Andrew Porter with the Mendocino County Sheriff's Office.

“She was involved in the drug world, hanging out with people that were involved in methamphetamine,” Porter, who has reviewed reports from Rachel’s case, said. “That lifestyle probably put her in an environment where she was vulnerable to somebody.”

MMIW activists point to centuries of prejudicial or ineffective government policies that entrenched within Native communities higher rates of poverty, substance and domestic abuse, and other issues that contribute to Indigenous women having a lower life expectancy rate than other groups.

Rachel’s brother and grandmother tried to get her professional mental health help, but said they were told by one psychiatric facility that, unless she was deemed a danger to herself or others, they couldn’t admit her involuntarily.

Rachel eventually floated off, slipping through the cracks. At some point, she disappeared.

Family and friends realized around 2012 or 2013 that she hadn’t been seen in a long time. Some had assumed she was living with an aunt, or a friend, or a cousin, before eventually coming to the panicky realization that she was gone.

“It was like, ‘Well where's Rachel? When have you last seen Rachel? I haven't seen Rachel,’” Tasheena said. “It was word of mouth because we're so small here: No one's seen Rachel.”

Delayed missing persons report, conflicting details

Two years after the burned body was discovered near Laytonville, Rachel’s brother and grandmother contacted county police.

Jacob had heard rumors that the bones that had been so unceremoniously dumped off the highway might be Rachel’s, and they asked police if the remains had ever produced a DNA sample. At that point, they officially reported Rachel as a missing person with Mendocino County.

Until then, the sheriff’s office had “no clue” Rachel was missing. “Nothing was ever relayed to us and nothing was ever done,” Porter said.

Mendocino County detectives later spoke with Rachel’s father Allen Sloan, who, according to Porter's reading of the case file, was surprised a missing persons report had been made. Porter noted that Allen said he had told Cahto tribal police Rachel was missing two years prior, though the county had never been notified.

But after many long years and with lots of contrasting voices, Rachel's case involves a fair amount of he-said-she-said. The timeline of certain events, including Rachel's actual date of death, is also hazy.

Two people who worked with the Cahto tribal police department at the time of Rachel’s disappearance, officer Christopher Gourley and Louie Torres, a consultant and former police chief, said Rachel’s father never spoke with them about her being missing. Allen could have mentioned it to others who were with the department, Gourley said, but he “doubts it.”

In a phone call with The Desert Sun, Allen maintained he doesn't recall telling the detectives he had previously reported Rachel missing. The last time he saw his daughter, he said, was one day in 2013 — he doesn't remember the date, "it's been so long" — when she was at home. Allen left to go somewhere with his cousin. "When I came back she was gone," he said.

Other relatives had been concerned about Rachel’s whereabouts well before they went to police, her brother Jacob said, but Allen had told them he thought Rachel was staying about 70 miles south on the Hopland Rancheria.

Allen flatly denies that. "I didn't say that," he said. He wasn't worried about Rachel during those two years after the body was found because she was always taking off with friends for long stretches of time; she'd "just pop in and pop out."

"I mean, there was nothing I could do about it," he said. "She was [over] 18 years old at the time. She's a grown up."

After The Desert Sun initially contacted Allen via letter, he said he ultimately decided to speak for this article because of the impact it could have on similar criminal cases. "It's too late for my daughter, you know," he said. "But I'd really like to help somebody else who might [be able to] find more information on their own case."

The unnamed body was finally identified as Rachel in August 2015 by comparing DNA samples from her father, grandmother and brothers. An earlier missing persons report likely would have led to a quicker identification, Porter said.

“I don't think she was reported missing [sooner] because she was one of our lost souls,” Tasheena added. “I don't want to say she was a transient or anything because she had a home. But she roamed.”

Lack of tribal police funding, resources

Meanwhile, the Cahto Rancheria Police Department has struggled for years to gather adequate funding, bolster its law enforcement capabilities and keep officers on staff.

The few officers with the unit have historically been limited in what duties they could perform and which laws they could enforce. Before entering into a special agreement with the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Cahto tribal police essentially had “the power of citizen’s arrest,” as Torres, the former police chief, described it. Cahto officers could issue citations, but only for violations of tribal law committed by tribal members on the reservation — with rare exceptions.

Without more expansive law enforcement powers, “when [county police] encounter a tribe where they do have tribal police, there's not that full trust, there's not that full dissemination of information, because that information is considered sensitive and only for sworn law enforcement only,” Torres said.

“And if the community knows that these guys are not sworn in, that basically their hands are tied, why would they go to them instead of the county sheriff?”

After a California tribe is issued a Special Law Enforcement Commissions agreement with the BIA, its tribal police officers can enforce federal criminal law on their reservation. Having that arrangement means tribal officers could also be granted access to the state-specific network California Law Enforcement Telecommunications System, where an officer can start an investigation and enter missing persons information. (Anyone, even if they are not a police officer, can submit tips or report information about an MMIW case to the agency's new Missing and Murdered Unit.)

Torres said Cahto was issued that law enforcement agreement with the BIA around 2016. But even if their officers had gained federal criminal jurisdiction during Rachel’s disappearance and homicide, Torres isn’t sure if it would have made a difference. Some tribal members just don’t want to be thought of as a “cop-caller snitch,” he said.

“With a lot of people living on the reservation, there's a lack of trust for law enforcement in general,” he said. “So you get a lot of people who are reluctant to come forward, or hear things but wait until much, much later to say anything.”

Money is a major problem, too. Cahto no longer employs any police officers because the grants their salaries depend on have either expired or were already spent, Tasheena said. Even with that funding, individual officer salaries hover around $18 or $20 an hour. California’s hourly minimum wage is $15.

“We've had a position advertised for months and we're just not getting anything,” she said. “It may be that the price is just too low for them.”

Mendocino County police also struggle with limited resources and in finding qualified applicants to fill staffing gaps; the sheriff’s office only has four detectives, Porter said in March. Some of those detectives have chased tips and third-hand information about Rachel to different corners of the state. Porter sent two of them to interview an inmate in Blythe, a small city on the Arizona border about 750 miles from Laytonville, several years ago. But that visit was a dead end.

“We owe it to Rachel, we owe to her family, to follow every lead that we can,” Porter said. “And unfortunately, there are times that we can't do it.”

Rachel’s case remains open, though no arrests have ever been made.

Because of the lack of physical evidence and degradation of Rachel’s body, Porter believes solving the case will rely on testimonies from others or a confession from the killer. “The only way this case gets made is if somebody has direct information, and they can't live with their conscience and decide to come forward with it,” he said.

But Rachel’s brother thinks county police could be doing more, that they never really tried to fully investigate. Officers have only spoken with Jacob about the investigation a handful of times over the years, he said.

Once, shortly after the DNA samples matched, Jacob went to the sheriff’s office to see how the case was going. He was told an investigation was underway and that officers would let him know if they found anything new.

“They never got back to us,” he said.

To this day, Jacob often hears rumors around Laytonville about who killed his sister. Without any leads from police, it’s the only information he has.

“With my grandma, and all my other family members here, I’ve gotten through it,” Jacob, now 30, said. If his older sister were still alive, she would be 32 this year. “But I still think about it. Like, are they gonna find out who did it or what?”

The remembering

Sometimes Tasheena thinks about the Laytonville of her childhood, in the 1980s, a time of youth when it seemed like nothing of note ever happened. Then Rachel’s mother died violently, her body discarded roughly 20 miles from where her daughter’s remains were left years later.

Tasheena had never been exposed to a murder or a serious crime like that before, and the drastic change in atmosphere was unsettling. Now, whenever she drives by the spot where Deborah Sloan’s body was dumped, someone will comment, “Oh yeah, that's where Debbie was found.” Locals tell stories about driving at night and seeing a woman walking along the road, as if Deborah’s spirit is wandering still.

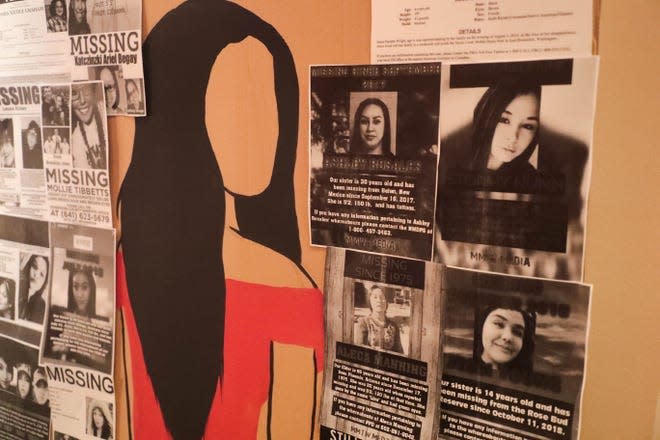

But the violence in Mendocino County didn’t stop. After Rachel’s remains were found in 2013, 23-year-old Khadijah Britton, another Indigenous girl Tasheena knew growing up, went missing from nearby Covelo in 2018. Other Native women in the county have been killed in the past decade, including Nicole Smith and Belle Rodriguez.

Over the years, Tasheena keeps coming back to simple questions. What is the correlation? What is happening here?

“It's all different stories of different young women, but it’s the same story in a sense,” she said.

As part of Rachel’s legacy, Tasheena knows there has to be a stronger support system at the tribal level for young Native girls. There should be more education about what trafficking and grooming look like, she said, and about how to find self-worth after extreme hardship.

Someone has to remember Indigenous women.

“I am Rachel’s cousin. I am her relative. And I do have this position,” Tasheena said of her role as vice chairwoman of the Cahto tribe. “I can use my voice to help.”

Contributing: Derek Catron, USA TODAY; Nora Mabie, USA TODAY Network.

Amanda Ulrich writes about Native American tribes and desert communities in Southern California for The Desert Sun, part of the USA TODAY Network. Reach out on Twitter at @AmandaCUlrich or via email at amanda.ulrich@desertsun.com.

This article originally appeared on Palm Springs Desert Sun: A Native woman’s killing remains unsolved. There are many others like her.