Canada's pandemic elections haven't seen the same polling problems the U.S. just experienced

The accuracy of political polling is being called into question again after the U.S. presidential election turned out to be closer than expected.

But while it's clear there was a problem with the polls in the United States, Canada's experience in three pandemic elections does not suggest that polling on this side of the border is experiencing the same issues.

When all the votes are finally counted in the U.S., Joe Biden is likely to beat Donald Trump in the national popular vote by about four or five percentage points. The polls had given Biden a lead of between eight and nine points, suggesting an error of roughly four points.

That's not terrific, but it matches the average performance of national polls in U.S. elections since 1972. Errors at the state level look likely to end up close to the historical average as well. Taking the aggregate, the polls missed the winner in only two states — Florida and North Carolina — while there were a couple of surprises in Senate races as well.

Polling is an imperfect science and some degree of error is unavoidable. But that error is supposed to be random. Instead, according to FiveThirtyEight, Trump beat his polls in 16 of 18 competitive races.

It was an echo of 2016, when Trump also defied the odds. Pollsters later concluded that their samples were short on white voters without college degrees — a demographic that went massively for Trump. Steps were taken to include more of those voters in polling samples this time, and the data suggested Biden was making gains among them.

That proved to be wrong. Nobody yet knows why for certain, but some plausible theories are being suggested (for example, by the Pew Research Center and Nate Cohn of the New York Times).

The theories point to everything from the U.S. political climate in 2020 to the COVID-19 pandemic. Could these factors be undermining Canadian polling as well?

If they are, we might have seen hints of them in the provincial elections held in New Brunswick in September and in British Columbia and Saskatchewan in October. There's no clear evidence that we did.

Theory #1: Republicans weren't picking up the phone

When pollsters build a sample, they want it to be representative. If it is, the demographics of the sampled population should match those of the broader population.

But what if the people willing to talk to a pollster aren't representative, regardless of their demographic profiles?

The theory goes that Democrats were more eager to participate in polls because they were more politically engaged than Republicans, as suggested by the number of people taking part in protests or donating to Democratic candidates.

The president's years of attacks on institutions, polls and the media may have eroded trust in them among his supporters. So, when a diehard Trump fan gets a call from a pollster (so the theory goes), he hangs up.

The combination of these two things would have made a polling sample disproportionately Democrat-friendly, even if the demographic profile of the respondents lined up with that of the population.

If there was a problem with engaged progressives and distrustful conservatives here, we would expect to see the polls go wrong in roughly the same way they did in the United States.

Instead, we see no such consistent pattern in Canada. The right-of-centre Saskatchewan Party was underestimated by about five points in polls conducted in the last week of that campaign, but that's the exception.

The polls in British Columbia were dead-on, with the B.C. Liberals (the main conservative option in the province) being overestimated by an average of just 0.3 points and the progressive parties — the NDP and the Greens — finishing within 0.1 percentage points of their average support in the last week of polling.

In New Brunswick, the Progressive Conservatives were underestimated by four points — but so were the Liberals.

This suggests no clear partisan bias in the polls in these three elections. There were some differences between provinces, but there was no problem across the board and certainly nothing out of the ordinary.

Theory #2: The turnout models were wrong

Another theory is that the models used by U.S. pollsters to estimate turnout were badly calibrated, making bad guesses about whether a respondent would vote or not. The fact that polls of all registered voters seem to have performed better than polls of likely voters suggests the turnout models were a problem.

Perhaps voters with an inconsistent history of voting — something which normally would mark them as less likely to vote in these models — did in fact vote and broke disproportionately for Trump.

In Canada, however, pollsters do not use turnout models (if some of them do, they don't say so publicly). Still, demographic differences in turnout have always been significant potential sources of polling error in any election on this side of the border. Nothing new there.

Theory #3: The pandemic changed everything

When discussing how the polls performed, it's impossible to ignore how the pandemic made this U.S. election like no other — and how this had a big impact both on polling and voting.

When COVID-19 kept people in their homes this spring, polling response rates increased.

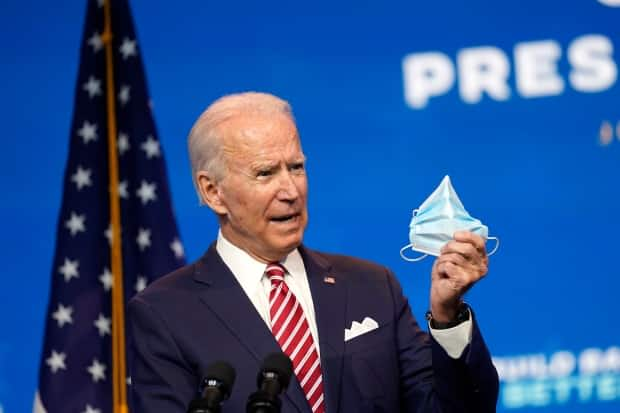

But polls have consistently shown Democrats taking the pandemic more seriously than Republicans. Driven in large part by the U.S. president, the seriousness of COVID-19 itself has become a political issue — something demonstrated in the first presidential debate, when Trump mocked Biden for diligently wearing masks.

This means the samples in polls might have had a disproportionate number of people staying home due to the pandemic, which would have made the sample disproportionately Democratic. One piece of evidence to support this theory is the fact that indications in the polls that areas with high rates of COVID-19 were swinging against Trump turned out to be false. Wisconsin was a COVID-19 hotspot around election day and it was one of the states where Trump beat his polls by the largest margin.

This difference in attitude had an impact on voting behaviour: Democrats were much more likely to vote in advance polls and (particularly) by mail, while Republicans were more likely to vote in person. This could have disadvantaged the Democrats — some mail ballots might not have been delivered and they generally have a higher rejection rate than those cast in person. The polls could not have accounted for this.

The same sort of political divide has emerged here in Canada, as demonstrated by the disparity in party support between mail and in-person voting in B.C. and Saskatchewan. (Only about three per cent of ballots cast in New Brunswick were by mail, and they are not separated from other special ballots in Elections New Brunswick's vote tallies.)

In Saskatchewan, the New Democrats beat the Saskatchewan Party by 1.6 percentage points in the 13 per cent of the vote cast by mail. In the remaining 87 per cent of the vote cast in person, the Saskatchewan Party prevailed by 33.9 points.

The NDP also did better in the absentee ballots in British Columbia. The B.C. NDP won the absentee vote by 21.4 points over the B.C. Liberals but carried the advance and election day in-person vote by just 9.8 points.

It's possible that the COVID-19 divide between right and left had the same impact on the accuracy of the polls in Saskatchewan as they did in the United States. But in B.C., where the percentage of the total ballots that were cast by mail (36 per cent) was comparable to the percentage in the U.S. (about 40 per cent), the polls were extremely accurate.

A perceived polling miss worse than the reality

In the end, the cause of the error in the U.S. is likely to be a mix of these and other factors, some of which are specific to the United States and some of which are not.

But the perception of how accurate the polls were in the U.S. has been greatly influenced by how the counting unfolded. On election night, Trump was leading in Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania and Georgia because the votes counted first were those cast in person. When the mail ballots were counted, the four states shifted to Biden.

Nevertheless, the narrative that the polls had completely failed was set. Had the final results of the election been known that night — that the Democrats had retaken the Midwest and won Arizona and Georgia for the first time since the 1990s — there would have been less focus on the accuracy of the polls.

There was also a shift in both B.C. and Saskatchewan when the mail ballots turned out to be enough to flip a few seats over to the New Democrats. They were not enough to matter, as the B.C. NDP and Saskatchewan Party had both secured comfortable majority governments.

But imagine what might have happened if these elections had been close enough for a handful of seats changing hands between the initial and final counts to make the difference between one party or another forming government.

When an election is close, polls generally aren't precise enough to tell us more than that the election is close, and that one party might have a slightly better shot. Even in a perfect world, polls will always be off by a bit — and the direction in which that error goes is usually unpredictable.

But they still help us understand the dynamics of a campaign. If there is one lesson for Canadians to take from how the polls performed in the United States, it's that polls are a good compass — not a GPS.