Do Canadians have the Constitution to tackle climate change?

American politicians have been known to wave copies of the U.S. Constitution in each other's faces during debates. Canada's leaders save that kind of action for the courtroom.

At more than 150 years old, the Constitution Act of 1867 has never been as relevant or as contested as right now, as the provinces and Ottawa fight over their roles in the defining issue of our times: climate change.

In the past month alone, constitutional precedent has been called on to attack and defend positions on both pipeline politics and greenhouse gas emissions.

In B.C., judges ruled Friday that the province doesn't have the right to stop diluted bitumen flowing through the proposed Trans Mountain expansion pipeline project which runs from Alberta to the Pacific Ocean.

And in Saskatchewan, their counterparts found Ottawa has the right to impose a carbon tax on provinces that oppose it.

'These questions become really pressing'

Both cases centre around the question of who best represents Canadian citizens — the province where they live, or the one with an eye to the concerns of the country as a whole?

And are those interests necessarily at odds?

Both cases also appear headed for the Supreme Court of Canada. That's a good thing, says University of British Columbia environmental law assistant professor Jocelyn Stacey.

At the very least, it adds a little spice to her classes.

"It becomes real when you consider questions about how do you regulate greenhouse gas emissions? How do you regulate oil spills? How do you regulate mining? All of these things that have a huge range of environmental effects," says Stacey, author of The Constitution of the Environmental Emergency.

"When you're approaching it from an environmental perspective, that's when these questions become really pressing."

'The environment is all consuming'

Stacey believes both the Trans Mountain pipeline case and the carbon tax debate are a good opportunity for Canada's top court to update its position on protection of the environment.

"The Supreme Court of Canada hasn't considered environmental issues in relation to the Constitution and the division of powers in a very long time," she says.

The courts have held that all levels of government have a role to play in protecting the air, land and water. But all governments also have to negotiate their own mazes of related economic and social interests.

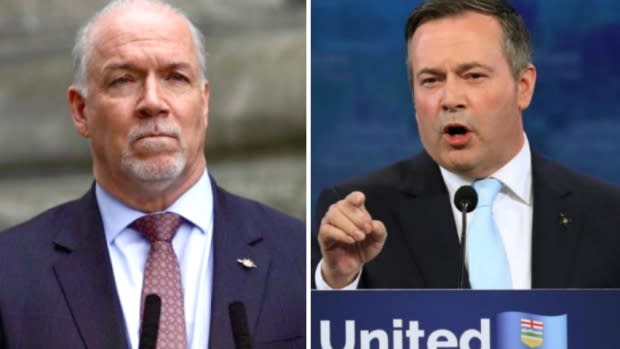

The B.C. NDP were elected on a promise to use "every tool" in their toolbox to stop the Trans Mountain expansion.

Alberta Premier Jason Kenney was elected on a similar note of defiance — to both B.C.'s position and the federal carbon tax.

And that's to say nothing about the complication that the federal government now owns the pipeline.

"The environment is all consuming, it's all around us. But to say that one level or the other has jurisdiction over the environment would tip the balance too far one way or the other," says Stacey.

"So the court's always trying to be mindful of that balance."

'Climate change is a global problem'

The debate over division of powers when it comes to the environment has been around for more than a century.

One of the key cases cited by British Columbia in defence of legislation proposed to restrict the increased flow of "heavy oil" from Alberta dates back to 1899, when a Quebec municipality tried to force the Canadian Pacific Railway company to remove rubbish from a ditch alongside its tracks.

The courts back then found that an interprovincial railway was subject to the "municipal code" of Quebec, but that the province couldn't regulate the "structure" of the ditch.

Nearly 120 years later, the same tension underlies the B.C. Appeal Court's finding on rules the provincial NDP wants to apply to the proposed twinning of a 1,150-km pipeline from Edmonton to the West Coast.

B.C. has a role to play when it comes to protecting its environment, the court said. But not if that means taking the constitutionally mandated control of a pipeline out of Ottawa's hands.

Likewise, the Saskatchewan appeal court found that the federal government has the right to impose a carbon tax over provincial objections in the name of "peace, order and good government."

"Climate change is a global problem and, accordingly, it calls for a global response," the appeal court ruling reads.

"In participating in these international processes, Canada is expected to make national commitments with respect to [greenhouse gas] reduction or mitigation targets. Those commitments are self-evidently difficult for Canada, as a country, to meet if not all provincial jurisdictions are prepared to implement ... emissions pricing regimes."

'There's not watertight compartments'

Stacey says she expected the B.C. Court of Appeal to rule as it did.

Lawyer Jack Woodward, who specializes in Aboriginal and constitutional law, says he believes the panel of judges got it wrong.

He sides with B.C. lawyer Joseph Arvay, who told the court the province is "not required to accept such a fate" when it comes to directly confronting problems in its own backyard.

He's hoping the Supreme Court of Canada will overturn the decision.

"There's not watertight compartments between what Canada can do and what the provinces can do. Everybody is allowed to make laws respecting the environment," he says.

"And in this particular instance, Canada certainly has the power to authorize, but British Columbia certainly has the power to regulate, what goes in the pipe and the financial liability of people who operate pipelines in the case of a spill."

'Canada must take action'

The kinds of environmental concerns at play in 2019 didn't exist in 1867. And divisions over the way to handle them aren't likely to vanish anytime soon — no matter what the courts decide.

Even the Saskatchewan Court of Appeal was split in its ruling.

The two dissenting judges in Saskatchewan summed up the nature of the debate in a chapter of their opinion entitled "Climate Change and Confederation."

"We agree that all levels of government in Canada must take action to address climate change," the judges wrote.

"Federalism in Canada means that all governments of Canada must bring all law-making power to bear on the issue of climate change, but in a way that respects the division of powers under the Constitution Act."

But how?