What the case of a man who vanished in the Village 23 years ago can tell us about Toronto's missing

Every time Joshua Hind hears about another person disappearing in Toronto's Village neighbourhood, he's transported back in time.

When he heard about the case of Tess Richey, the 22-year-old who went missing in the Church and Wellesley area in late November, Hind found himself a teenager again, living three hours away from Toronto, helplessly trying to find his own loved one.

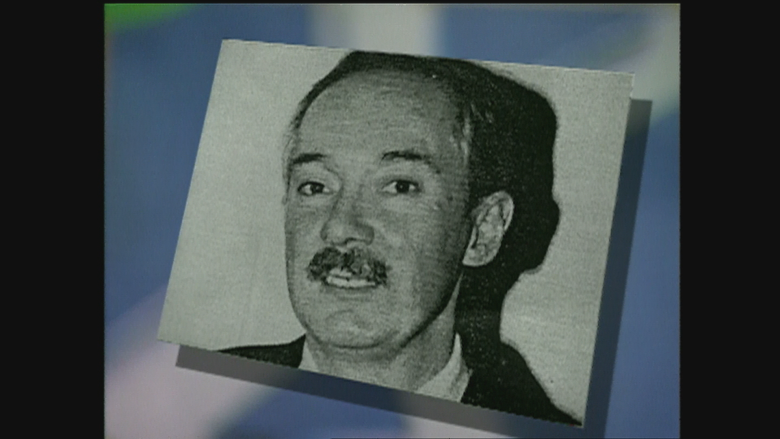

Hind's uncle, Larry Arnold, disappeared from the area more than two decades ago.

The circumstances bear a haunting resemblance to Richey's case. Arnold's body was found more than four weeks later, less than a 10-minute walk from where he was last seen.

'How far we haven't come'

Days after her disappearance, Richey's lifeless body was found in a stairwell just steps away from where she was last seen with an unknown male. Her family would later tell CBC News it was Richey's own mother, who had travelled to Toronto from North Bay, who found her.

"That got me thinking, really, about how far we haven't come with regards about how missing persons are dealt with," Hind told CBC News.

"It brought to mind the similarities between my uncle's story and Tess's story... and that it wasn't the police that found them."

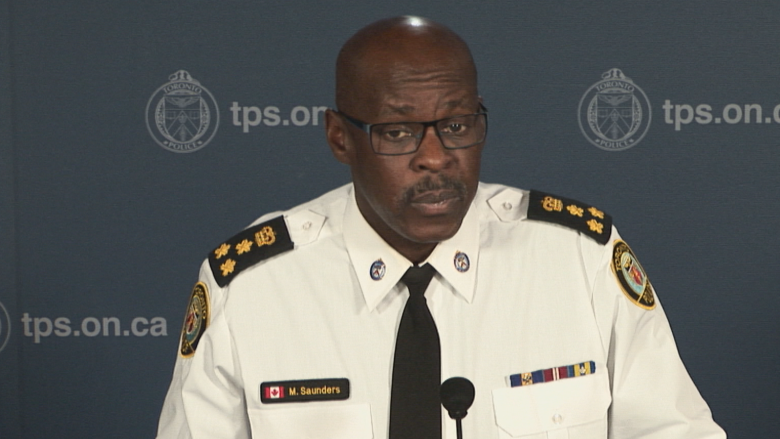

His comments come on the heels of a news conference on Friday, in which Toronto Police Chief Mark Saunders announced the force is reviewing its handling of Richey's disappearance and exploring how it might better respond to missing persons cases. The acknowledgement followed months of mounting concern over whether police have been doing enough to solve a spate of disappearances in the area.

At least seven people have gone missing in the downtown core since last spring. That number includes Richey as well as 27-year-old Alloura Wells, a transgender woman who vanished over the summer and whose remains were identified last week.

Police also provided an update on the still-unsolved disappearances of Selim Esen and Andrew Kinsman. They said those cases are unrelated to the 2012 Project Houston investigation, which centred on three other men who vanished from the same area that year.

'They weren't the ones to find him'

"Uncle Larry" as Hind knew him, lived in the Chatham area and travelled to Toronto about six times a year. His visit in October 1994 was his last.

He was last seen on Oct. 14 in the Church and Wellesley neighbourhood, leaving a bar with another man. After that, the case went cold.

The community put together a poster campaign as police investigated. Hind later learned the detective on the case wrote two Crime Stoppers stories hoping for leads. But apart from him, the family believed, few other resources were put into pursuing the investigation.

It would be four years before Paul Alan Hachey confessed to the 46-year-old's murder, facing DNA evidence that linked him to another homicide and multiple sexual assaults, said Hind.

A friend, CBC News reported at the time, said Arnold had left an answering machine message saying he wouldn't be able to meet for dinner and that he was "having fun."

His body was found more than a month after he disappeared, in a wooded area near Rosedale's million dollar homes across from David Balfour Park, which was described at the time as an area "known for sexual cruising."

"Did they do enough? I don't know," Hind said. "He was found by a hiker who happened to be walking through that area. It's hard for me to say... but they weren't the ones to find him."

'High risk' of hate crimes

Much was made at the time, says Hind, of the fact that Arnold was gay, and that he was last seen leaving a gay bar with another man.

"It was as though his death was just a hook-up gone wrong," Hind told CBC News. "Every newspaper article, every TV story made a point of saying he was gay, as though that was somehow relevant to his death."

In 2001, Hachey was convicted in Arnold's murder, says Hind, after pleading guilty to another murder and sexual assault.

In the end, it turned out that Arnold was the only man Hachey killed, Hind says. Investigators never did find a motive for his death, but Hind wonders if the perception that being gay meant living a high-risk lifestyle played a key role in his uncle's case going cold.

"The high risk is that gay people are more at risk of being targeted for hate crimes and for abuse," said Hind. "And police need to take these cases maybe a little more seriously than they would in other areas — because there are more factors that come into play when someone goes missing in The Village."

"Gay people, LGBTQ are still the targets of crime and we certainly can't blame them for being extra on edge when, so far, five or six people have disappeared from that community."

Speaking to reporters Friday, Saunders said part of the reason for launching the probe into how it handled Richey's case was to find out what police knew, when they knew it, and assess how they might improve their processes.

That's good news to Nicki Ward, director of the Church and Wellesley Neighbourhood Association.

"I'm really glad professional standards are being called in," she said. "I have never seen the relationship with Toronto police break down to such a degree."

The force is now supplying four community resource officers to keep watch over the area. Meanwhile, some in The Village have banded together to try to set up a walk-safe program to help ease fears in a neighbourhood on edge.

Initiatives like that — and the fact that many set up their own search parties for the missing— are also something Saunders says raise concerns.

"I have to question whether or not, as a service, we're offering the right value to the community."