Censorship then and now: books banned by Vatican explored by Fredericton prof

While the limits of free speech and the debate over censorship is a feature of modern times, a new book by a St. Thomas University history professor shows this discussion has roots going back centuries.

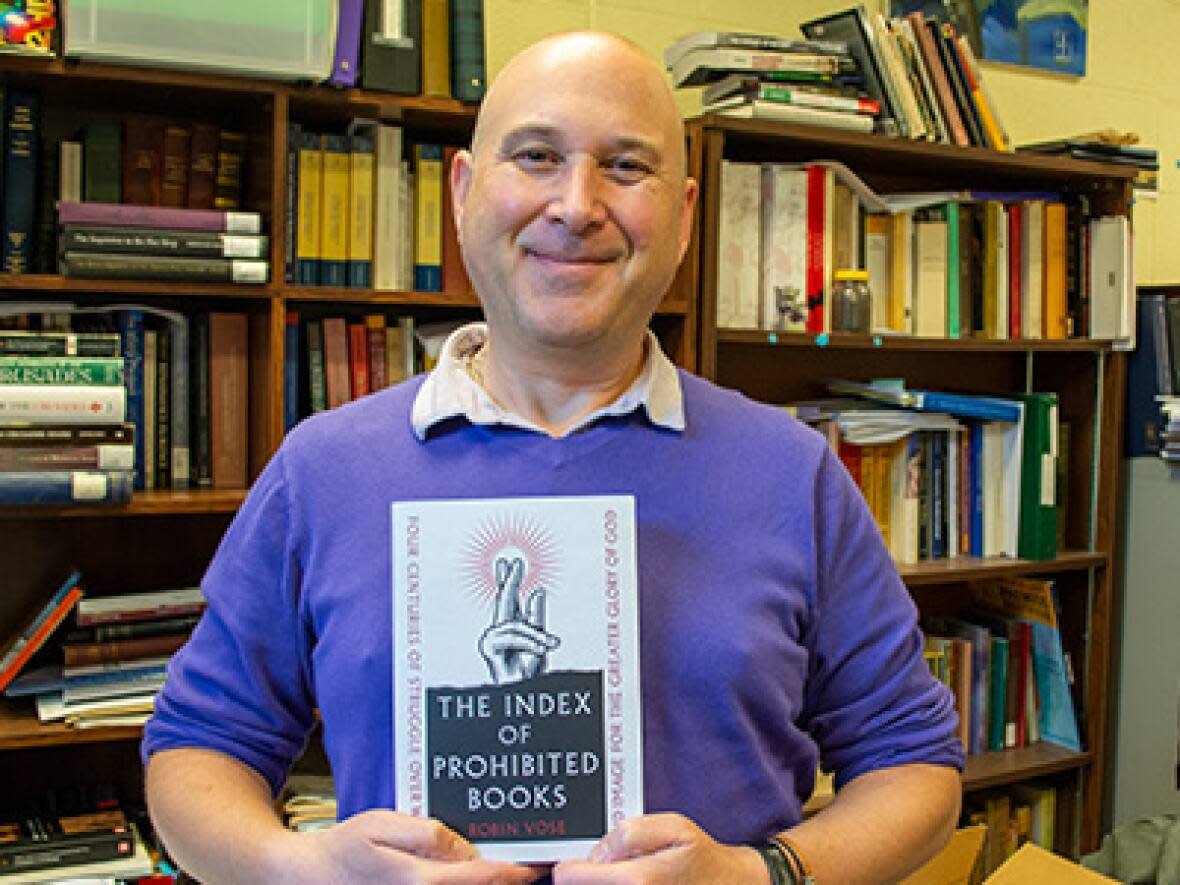

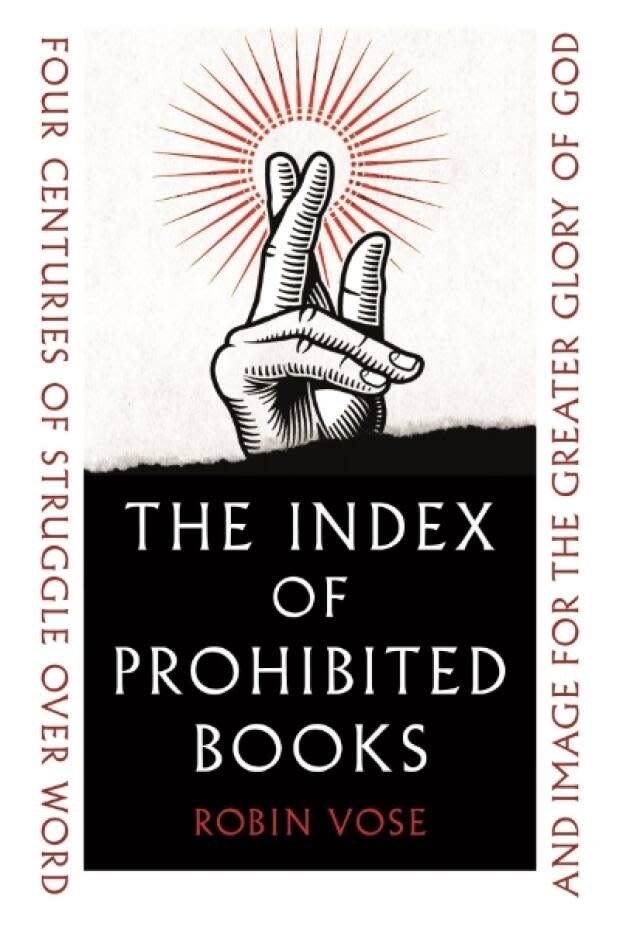

The Index of Prohibited Books: Four Centuries of Struggle over Word and Image for the Greater Glory of God, by Robin Vose, explores the history of book banning by the Catholic Church going back 400 years.

The "Index Librorum Prohibitorum," or list of prohibited books, was first codified in 1560 but has its origins in other lists going back to the 900s.

The list was updated up until 1948 and was abolished by Pope Paul VI in 1966.

While the lists are usually thought of as strictly Vatican documents, it wasn't the church that started them.

It was universities, now seen as bastions of free speech and inquiry, that started compiling lists of banned books, said Vose.

"It was university professors at first who were making lists of Protestant books that they didn't want in the course curriculum for students to see," he said.

"[It] went viral as it were, in a 16th century way, because the Spanish and Portuguese Inquisition thought, 'Well this is a great idea.'"

Going mainstream

It wasn't until the 1500s that the church became officially involved.

"That's when Paul IV, who himself was a former inquisitor, decided to make a list that was more universal, including not just Protestant theologians and a few Jews and Muslims but also texts that people will know," said Vose.

Writers and thinkers to make the list over its long history include astronomer Galileo Galilei, Les Misérables author Victor Hugo and Daniel Defoe, who wrote Robinson Crusoe as well as writers in the mid-20th century.

"Jean Paul Sartre is on there, Simone de Beauvoir. One of the last things to be banned was actually Nikos Kazantzakis' The Last Temptation of Christ, which was made into a film," said Vose.

Contemporary censorship

Vose's book comes at an opportune time for discussion of censorship and freedom of speech. Several school districts in the United States have banned books which their detractors promote controversial subjects like LGBTQ issues and critical race theory.

In Canada, the annual Free to Read week is organized by the Book and Periodical Council, which promotes "intellectual freedom," according to its website, and inspires discussions about book censorship.

Social media networks have also struggled with how much they should or shouldn't limit potentially harmful speech, like potentially false critiques of politicians and anti-vaccination material.

This came to a head with the purchase of Twitter by tech billionaire Elon Musk who called himself a free speech absolutist but has also been criticized as silencing negative views of himself on the platform.

When writing the book Vose found he was surprised by how often he sympathized with the censors.

He said they were banning texts that they truly thought were dangerous, even if now it may seem ludicrous to think so.

He even said there are some texts that could be targets for banishment today, especially in a climate wary of poor medical advice.

"There's a lot of quack science weird cures for cancer and things like that, that the Spanish Inquisition banned because they checked with medical authorities and said, 'Yeah, this is, this is dangerous information to be spreading.'"

Vose said he doesn't have an easy answer for people looking to ban texts in the modern world, but society has to consider where it draws the line when it comes to books that promote disinformation that could hurt people.

"What I hope is that my book and discussions about this subject can help people to at least think things through more fully and not necessarily fall into knee jerk reactions," said Vose.