Copycat pot edibles that look like candy are poisoning kids, doctors say

Dr. Jane Pegg couldn't believe her eyes when she saw the pot edibles that had poisoned a two-year-old who had been rushed to the emergency room in October.

"It so shocked and appalled me … the package looked almost identical to gummies that are sold as candies in the store," the Nanaimo, B.C., pediatrician said.

The boy wasn't moving and was having trouble breathing.

His distraught mother had accidentally given him marijuana-laced gummies that contained a massive dose of THC — a psychoactive compound in cannabis — thinking it was candy.

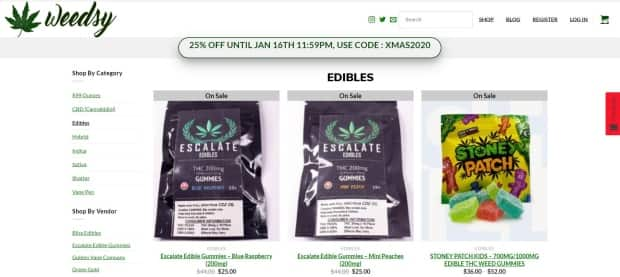

The edibles belonged to the child's grandfather, who has arthritis, and are sold under the names "Stoney Patch" and "Stoner Patch."

They look so much like the Sour Patch Kids brand that the company behind that candy, Mondelēz Canada Inc., successfully sued last January for trademark infringement.

"I don't know why the companies that are selling these products are not being shut down, not being fined, not being charged," said Pegg.

Cannabis-infused edibles — including gummy candies, chocolate or baked goods —that are sold legally must follow Health Canada rules including a 10-milligram limit on THC.

They also can't be packaged with images or bright colours that can appeal to children, need to have child safety warnings and be child-resistant.

But copycat products often break all the rules.

Go Public found hundreds of websites selling illicit edibles with packages designed to look like all types of candy and chocolate bars — everything from Sour Patch Kids, Pop Tarts, Snickers chocolate bars and more.

The sites are part of a huge and illegal marketplace that operates openly, under the nose of the government and law enforcement.

"These websites [are] operating quite flagrantly," said lawyer Trina Fraser, who specializes in cannabis regulatory law.

"I think there is a certain amount of jurisdictional struggle over whose responsibility [it is], because these enforcement actions cost money and someone's going to bear the cost of that," she said, referring to provincial, territorial and federal governments and the multiple police forces that are tasked with enforcing the rules.

The two-year-old Pegg treated spent the night in hospital and was released the next day.

Pegg's colleague, Dr. Jodi Turner, has seen similar poisonings in the same ER.

"Sometimes they [children] need to be kept on a monitor. You're looking for whether or not their heart is stable. You're looking at whether or not they develop seizures or need a ventilator to breathe," she said.

Pot became legal in Canada in October 2018; edibles were legalized a year later.

Since then, regional poison centres across the country have reported a spike in unintentional poisonings of children and teens involving edibles — though it is unclear how many of those cases involved illicit, lookalike packages. Data was not available from every province and territory.

Such poisonings roughly doubled in B.C., Nova Scotia and Quebec between 2019 and 2020. B.C. saw almost 100 cases in 2020. Ontario, Manitoba and Nunavut, which report their poisonings together, reported 166.

No fatal poisonings of children or youth involving just cannabis have been reported to Health Canada since legalization in 2018.

After treating the toddler, the first thing Pegg did was contact Health Canada, to ask how to report the poisoning — but no one got back to her.

"I followed their reporting guidelines, I followed up by phone … [but] had no response until you [Go Public] contacted them."

Pegg finally heard back in January, more than two months after she reported the incident.

WATCH | Go Public explores the prevalence of pot edibles that look candy:

Health Canada tells Go Public that Pegg's email was sent to a "generic" email account which gets a lot of messages and there was a "delay in processing the information."

Health Canada also said, via email, that after seeing an increase in such reports, it issued an advisory in August about accidental ingestion of illegal edible cannabis products by children and launched "extensive public education and advertising campaigns … to encourage adults to store all cannabis securely."

Statistics Canada says an estimated 42 per cent of cannabis users — 743,800 Canadians who responded to the survey — got pot from illegal sources in 2019.

'Whack-a-mole'

In its January email to Pegg, Canada Health said she should contact the RCMP or her local police department.

But it's not quite that simple, according to the co-chair of the drug advisory committee at the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police.

Mike Serr says there are at least 1,100 illegal sites operating just in Canada, and while police have had success shutting some down, the problem is bigger than they can handle.

"I wish I had a better term, but really whack-a-mole describes it quite well. When we hit one down and get rid of it, four more pop up," said Serr, who is also chief of the Abbotsford, B.C., police department.

Serr says the websites are often run by organized crime and warns the products, which are often cheaper than the government-regulated cannabis, are untested, unregulated and run the risk of being contaminated.

Police are talking with banks to see if they will flag pot purchases and stop the flow of money to the illegal sites, he says.

"That will help disrupt the illicit market online … [banks] know that they should not be allowing those transactions, that they're illegal transactions.

"It's just really a matter of being able to identify the illegal and the legal online stores correctly."

He says he'd like to see the federal government fund a task force that specializes in shutting the illegal websites down.

The RCMP tells Go Public it has implemented what it calls a "national investigative strategy," working with the Canada Border Services Agency, Canada Post, Health Canada and municipal and provincial police forces to go after the organized crime groups running the sites.

Illegal websites look legit

Complicating the issue is how the websites look. In many cases, it's hard to tell the difference between legal and illegal sites, says Fraser. Adding to that confusion, she says, are the different rules in different provinces about how pot is sold online.

Ontario, for example, has one legal, provincially run cannabis website that can sell and ship and private licensed retailers that can sell online for in-store pickup. Saskatchewan and Manitoba allow private, licensed retailers to sell and ship online.

"So, in some cases," says Fraser, "it becomes very tricky for the public to understand what is a licensed retailer and what is not."

Possessing cannabis purchased from illicit websites is also a crime.

Public Safety Canada says it has a plan that will crack down on the thriving, illicit market. That "action plan" was announced last March, but hasn't been implemented.

It includes increasing public education and working more closely with police, the provinces and territories to identify and shut down the sites.

The plan also proposes "putting search engines, social media, and payment platforms on notice about their legal responsibilities in relation to illegal online cannabis stores," wrote spokesperson Magali Deussing in an email to Go Public.

She says, "work is underway" to put the plan into action and that Public Safety Canada will review the effort to displace the illicit market, as part of a its review of the Cannabis Act scheduled for the fall.

'Families feel terrible'

Pegg says action is long overdue.

"Surely in this day and age they can shut down these websites," she said.

In the meantime, she's keeping a close eye on the reports of kids poisoned by pot edibles. She says the long-term impact on a child's developing brain is unknown.

Go Public asked to speak with the two-year-old's mom about the family's experience, but she declined the interview.

"Families feel terrible. Especially when it happens in another family member's home or... where [given] the packaging, there is no reason to think it contained THC," Pegg said.

"They need to address this, online sales of these these products because it's really placing children and families at risk."

Submit your story ideas

Go Public is an investigative news segment on CBC-TV, radio and the web.

We tell your stories, shed light on wrongdoing, and hold the powers that be accountable.

If you have a story in the public interest, or if you're an insider with information, contact gopublic@cbc.ca with your name, contact information and a brief summary.

All emails are confidential until you decide to Go Public. Follow @CBCGoPublic on Twitter.