Corrections Canada pushing ahead with electronic monitoring of offenders

Canada's prison service is pushing ahead with a plan to track high-risk offenders with electronic monitoring anklets, despite concerns that technological glitches could set off false alerts.

A February briefing deck from the Correctional Service of Canada shows a three-year pilot program is set to roll out nation-wide across five regions between May and October this year.

The documents were obtained by the Criminalization and Punishment Education Project based out of the University of Ottawa and Carleton University and provided to CBC News Network's Power & Politics.

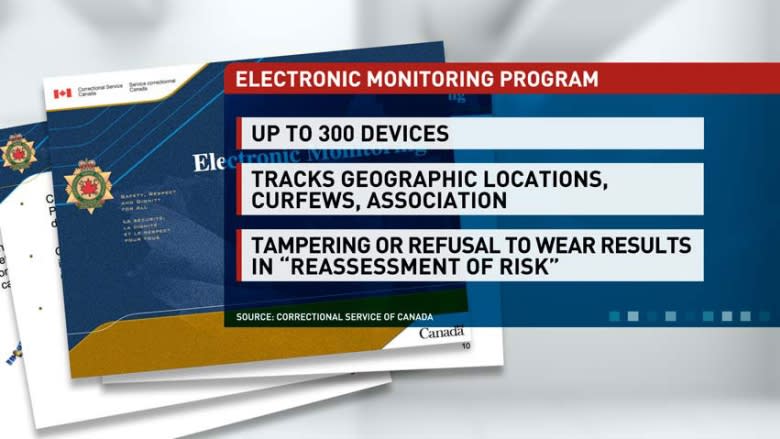

According to the presentation deck, the pilot program will use up to 300 "hybrid" devices that use GPS technology to track offenders through exclusion and inclusion zones, then revert to radio frequency when the offender returns home. The system is designed to preserve battery life and minimize GPS "drift" that affects accuracy, the document reads.

Justin Piche, a criminologist at the University of Ottawa, has not seen evidence that past concerns around unreliable technology have been adequately addressed. And he worries that could mean inaccurate reads that signal breach of conditions that could send an offender back to prison.

An evaluation of a smaller, two-province pilot in 2008-09 found "challenges" due to drained batteries and false tamper alerts.

The CSC documents warn of serious consequences for offenders who violate conditions of their release.

"Any refusal to wear a monitoring device or tampering with the device will result in a reassessment of risk," the document reads.

CSC spokeswoman Veronique Rioux said a determination that an offender has breached a condition would not be made on the basis of electronic monitoring alone.

"As with any technology, there is always a possibility of system malfunctions, which is why decisions are never based solely on EM information," she said.

"Through knowledge gained from its previous pilot, and continued communications and engagement with other agencies currently using electronic monitoring, CSC has ensured that its training and response protocols take into consideration the possibility of technological malfunctions in any assessment of whether an offender has breached a condition."

Rioux said ongoing risk assessments, special conditions, curfew checks and contact with police would also be used to supervise offenders in the community.

Invasion of privacy or risk management?

Piche also believes electronic monitoring infringes on personal privacy and civil liberties by tracking an offender's everyday activities. He also said it could also be overused after it becomes part of the system.

"Once you open the door to that and people from the parole board know that they have access to this tool, once the pilot project is over and they do actually implement it….the tendency is towards risk aversion and net widening," he said.

But John Muise, a former 30-year Toronto police officer who subsequently spent five years as a member of the National Parole Board, believes electronic monitoring is a valuable tool for keeping tabs on potentially dangerous people.

Devices track where someone is, not what they're doing, Muise said, adding individuals are ordered to wear the devices for a reason.

"You're an offender, you're serving a sentence, and there are expectations around managing your risk," he said. "If someone is putting this on you, they're not being cavalier about it. They're doing it because it's recognized that you're an offender, you've done something bad, and you continue to be a risk to re-offend."

Legal changes under the Corrections and Conditional Release Act that came into force in June 2013 allow CSC to require an offender to wear an electronic monitoring device. They are used on high-risk offenders on day passes, work release or parole to track curfews, geographic locations and association with other offenders.

Catherine Latimer, executive director of the John Howard Society of Canada, said her key concerns are around whether electronic monitoring could hamper successful transition back to the community by reducing one-on-one human contact with parole officers and adding to the stigma by branding the offender with an anklet.

"It's not going to be helpful for people blending in if people are aware they're wearing these electronic monitoring devices," she said. "Their employment prospects are pretty tough anyway. I don't know if it would make it categorically worse — but it wouldn't help."

Latimer also has concerns about accuracy of the technology and hopes the pilot program will be independently evaluated.

According to the documents, CSC will complete a formal research report with recommendations to the minister of public safety after the three-year period.