No one will be untouched by a warming planet, scientists say

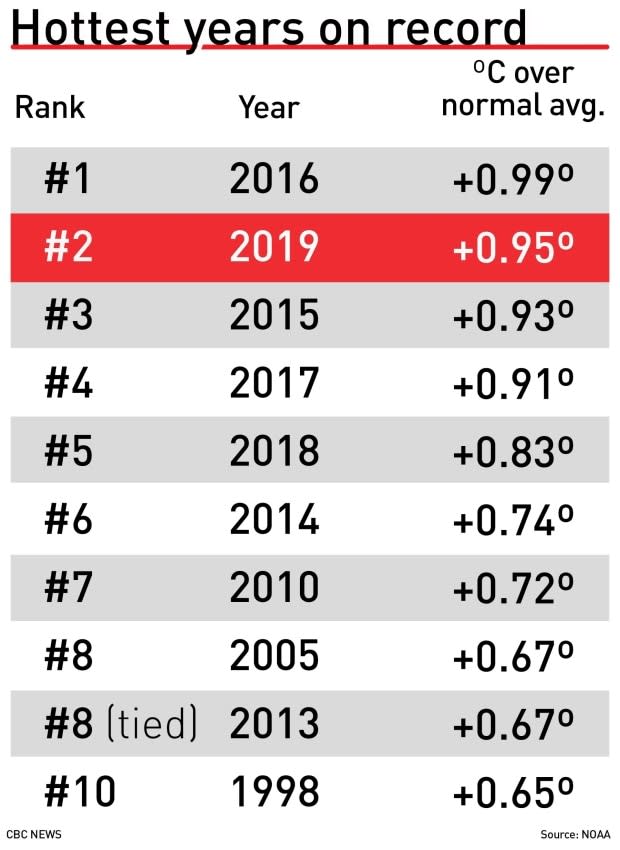

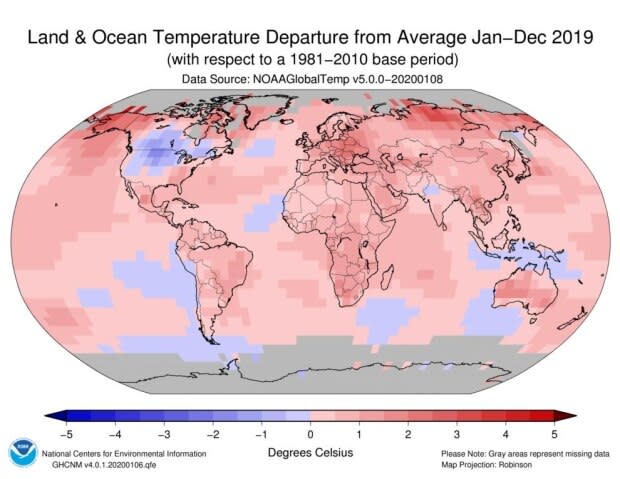

On Wednesday, NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) released their annual report on global temperatures and climate conditions — 2019 was the second warmest year on record, and the past decade was the warmest ever.

These types of temperature milestones are the norm now; every month it seems another record is set, and every year we reach another global warming milestone.

In fact, the hottest years on record have all occurred since 2005, according to the report.

But scientists say rising heat is about more than just numbers; behind those statistics are consequences for people, their livelihoods and our delicate ecosystems.

Climate change is costing cities as they try to adapt and mitigate. Farmers are facing increasing challenges, which can lead to consumers paying more for food. Extreme weather disasters are on the rise in Canada and costing insurance companies, leading to higher premiums. People are dying in heat waves which are set to become more frequent as the planet warms; and hurricanes are stalling, meaning more people are in danger for longer periods of time.

"In my line of work, we do track the numbers and we do try to quantify the behaviour of the climate system, but ultimately what really matters is where it intersects and impacts with the people we love and the things we do," said Deke Arndt, chief of the global monitoring branch of NOAA's National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI).

In our normal, day-to-day lives, the effects of a warming planet may not be so evident to most Canadians. But to some, it's all too real.

The most dramatic changes are found in the north. The region is warming almost three times faster than the planet as a whole, resulting in record-low sea ice levels in the Arctic and melting permafrost.

These occurrences have consequences. They're taking a toll on ecosystems — and on the people who have called the cold, icy area home for centuries.

Inuit are losing their homes. They are losing their way of life. They are falling through the rapidly thinning ice while hunting. The warming is also affecting the mental health of people who had cherished longer winters and persistent cold.

To people who have long relied on the consistency of the cold north, the change is all too real.

From farms to our pocket books

Farmers are also particularly vulnerable to climate change.

"Some people who work in weather-sensitive sectors such as agriculture … are seeing [climate change] on an annual basis, and they're seeing [it] through greater extremes, and they're also seeing it in the greater variability, the wild swings," said Dave Phillips, senior climatologist with Environment and Climate Change Canada.

Phillips' annual list of Canada's top ten weather stories cited the terrible farming season in the Prairies in 2019. The weather went from dry before the planting season even began for many, to too wet from June to August, followed by an early snowfall at the start of harvest time in September. This meant a lot of crops remained unharvested.

John Guelly, chair of the Alberta Canola Producers Commission, said the 2019 growing season was "the harvest from hell."

Guelly, who has been a farmer for the past 30 years just northwest of Edmonton, plants canola, wheat and barley, with 1,000 acres of crops.

"In our particular region, where I farm, it's actually been the fourth really lousy harvest season we've had in a row," he said. "It's definitely taking its toll on people."

But not all the challenges have been the same. In 2018, smoke from the B.C. fires reduced sunlight, for example. And with climate change forecast to create drier conditions in some regions, this may be a sign of things to come.

"If you'd asked a farmer before Christmas what they wanted for Christmas, it was 'Can the growing season be normal next year?'" Guelly said. " What's normal anymore? We're not sure."

Global impacts

The fires raging in Australia are just a recent example of the challenges a continuously warming Earth will present. To date, 28 people have died, including two firemen, and millions of animals are thought to have perished.

Then there are hurricanes. In 2019, Hurricane Dorian sat almost immovable above Abaco Island in the Bahamas for more almost 24 hours, killing at least 70 people.

Heat waves killed an estimated 1,500 people in France in 2019. The good news is this is far below the 2003 heat wave that killed an estimated 30,000 across Europe, with 14,000 in France alone.

And here at home, a heat wave killed 66 people in Montreal in 2018.

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), an international humanitarian medical organization, believes places like South Asia and the Pacific region, the Middle East, the Sahelian Belt, and Southern Africa are particularly at risk.

Carol Devine, a humanitarian advisor at MSF focusing on human health and climate change, said she's concerned about what the future holds.

"Vulnerable people tend to become more vulnerable, and climate change exacerbates health issues," she said.

"Climate-sensitive diseases — that concerns us," said added. "All these pieces interconnect somehow: climate-sensitive diseases, water and food insecurity, malnutrition related to drought or micronutrients or salinity coming into crops."

She's seen certain diseases move into areas that hadn't faced them before, leaving some local doctors unable to adequately treat patients.

"There are already so many vulnerabilities, so what's to come?" she said.

While not all weather events are a result of climate change, climate change can exacerbate them. It upsets a delicately balanced Earth system.

And scientists are getting better at teasing out weather from the changing climate, improving attribution.

But, without curbing greenhouse gas emissions, the future contains a lot of upheaval and big impacts on people's lives.

"No area will be immune from it," Phillips said.