CSIS weighed whether rail blockades supporting Wet'suwet'en could be classed as terrorism

Canada's civilian spy service assessed whether First Nations land rights activists who disrupt trains should be classed as a "terrorist threat" to national security alongside the likes of Al-Qaeda and ISIS, according to declassified documents.

But the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) eventually decided the label wouldn't stick after probing the issue in secret, internal studies whose findings were shared with government officials in an unclassified March 2021 counterterror briefing.

CSIS reached this conclusion through analysis of the Canadian criminal code, under which, to be considered terrorism, interference or disruption of essential services must inflict death or injury through violence, or otherwise cause serious risk to public health and safety.

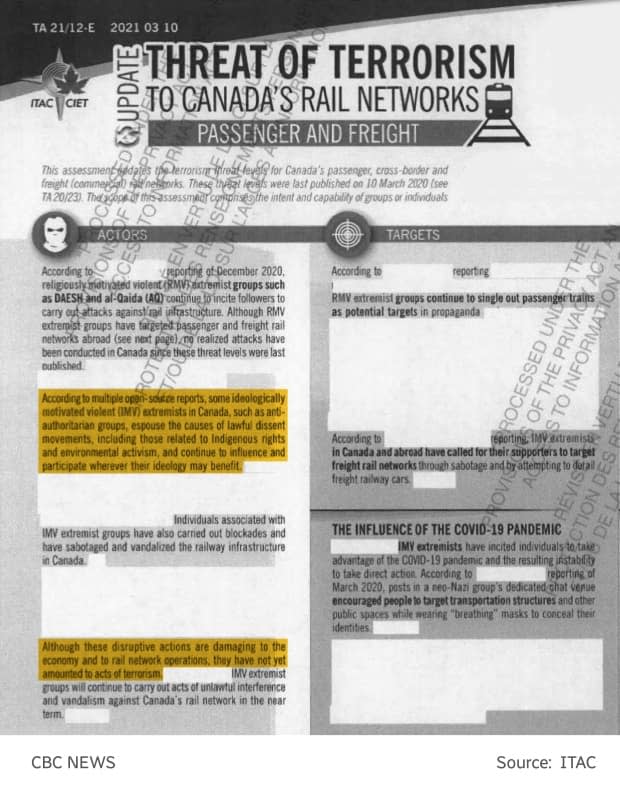

"Unsophisticated acts of unlawful interference [like blockades] do not cross the terrorism threshold," the Integrated Terrorism Assessment Centre (ITAC) said in a report released through access-to-information law.

"Although these disruptive actions are damaging to the economy and to rail network operations, they have not yet amounted to acts of terrorism."

Concern tied to blockades, solidarity protests

ITAC employs officials from across Canada's security and intelligence bureaucracy, and generates reports for federal leaders based on openly available and classified sources.

It's housed under CSIS, which is tasked with monitoring and reporting on potential threats to national security stemming from hostile acts of subversion, sabotage, espionage and terrorism.

Though heavily censored, the documents confirm the spy service's concerns were tied in part to the February 2020 Wet'suwet'en solidarity demonstrations, which disrupted rail corridors for weeks.

Wet'suwet'en hereditary chiefs oppose construction of the Coastal GasLink pipeline through their nation's territory in northern B.C. Following an armed RCMP raid on road blockades that were stopping construction workers from getting through, dozens of protests popped up across the country to show support.

CSIS was also worried about a standoff over a housing development in Caledonia, Ont., which Haudenosaunee activists from nearby Six Nations began occupying in July 2020 as part of a long-standing land claims dispute, dubbing it 1492 Land Back Lane. Activists mounted road blockades and shut down a CN rail line following police raids in August 2020 and October 2020, respectively.

The 247-page release begins with a November 2020 report on the unrest in Caledonia, already published by APTN News, where the service raised "notable concerns" about the camp's impact on critical infrastructure in southern Ontario.

Then on Dec. 15, 2020, CSIS's Intelligence Assessments Branch penned a classified report sparked by a decision by U.S. prosecutors to lay terror charges against two women accused of trying to sabotage trains in Washington state.

"The perpetrators had allegedly acted in support of the [2020] Wet'suwet'en pipeline protests and had links to anti-authoritarian movements that seek anarchy and advocate for civil unrest," ITAC said.

ITAC assessed, however, that "these acts unlikely constitute terrorism, or defined as such in Canadian law, and likely had more to do with vandalism against a symbol of perceived [oppression]."

Even so, CSIS was evidently worried about anarchists meddling in First Nations-led demonstrations, describing these groups as agitators who latch on to democratic dissent to stir up social disorder "wherever their ideology may benefit."

And while not quite terrorists, the documents indicate CSIS labels First Nations activists and allies who engage in blockades as "ideologically motivated violent extremists," and thus potential national security threats who warrant state surveillance.

Criminologist calls reports 'troublesome'

Jeffrey Monaghan, an associate professor of criminology at Carleton University, analyzed the documents and found much of this concerning.

Terrorism prosecutions have slowed in recent years, Monaghan said, so he called it interesting to see CSIS "shopping around" the idea of potentially laying terror charges against rail disrupters.

"We've expanded the war on terror so broadly that Indigenous rights activists are being scrutinized as potential terrorists," he said.

"It's really a symptom of the war on terror stretching out so far and developing all these resources that they have to be used."

Monaghan fears ITAC is disseminating "spurious" claims through the federal security bureaucracy that discredit First Nations-led activism politically, painting it as the work of would-be terrorists, violent extremists or interloping agitators.

He said the tendency to ascribe direct action tactics by First Nations to subversive outsiders is part of CSIS's institutional culture going back years. In 1990, Assembly of First Nations National Chief Georges Erasmus denounced this narrative as "implicitly racist."

Monaghan called the documents' use of extremist framing "troublesome" because ITAC reports circulate internally to other agencies, and said they offer "pre-emptive" intelligence police can use to justify heavy-handedness.

"It just raises so many questions of why they would be so quick to try and de-legitimize Indigenous-led protests by trying to, basically, say it's antifa," said Monaghan.

"Their willingness to just almost skate over the actual political grievance, the actual political movement, and all of a sudden latch on to these de-legitimizing tropes really paints a picture internally of the policing-intelligence culture that does not take Indigenous affairs seriously."

No comment from CSIS

CSIS declined to make its director available or directly answer questions from CBC News, saying via statement that it doesn't investigate legal protests or democratic dissent, and that the service is bound by the definition of national security threat in the CSIS Act.

The service declined to address Monaghan's contention that CSIS should not be monitoring non-violent, unarmed First Nations activism under the category of potential terrorist threats, even if these actions are allegedly unlawful.

CSIS media relations officer Eric Balsam said the service is investing in trust-building activities and exploring opportunities for engagement with First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities. When asked which communities the service has engaged, Balsam said that information is classified.

"We do not publicly comment, or confirm or deny the specifics of our investigations, operational interests, methodologies or activities," Balsam said.

All of CSIS's activity and records are subject to oversight bodies — the National Security Intelligence Review Agency (NSIRA) and the National Security Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians (NSICOP), Balsam added.

People with concerns about CSIS's activities have recourse to NSIRA's complaints mechanism, he added.