'Dangerous precedent?' How the averted debt ceiling crisis could become new Washington norm

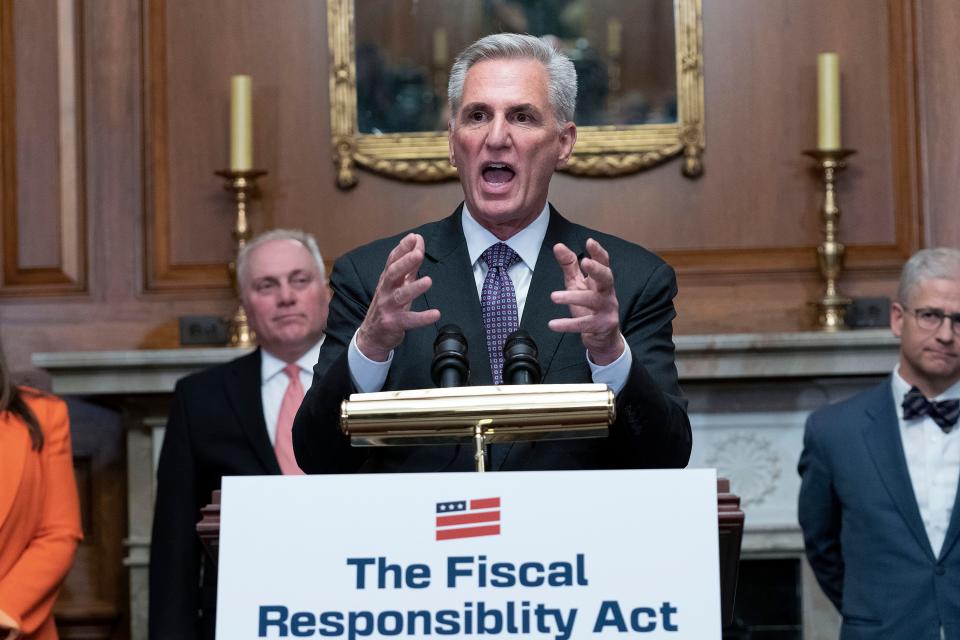

WASHINGTON − With President Joe Biden prepared to sign a debt-ceiling bill loaded with Republican spending cuts, Speaker Kevin McCarthy proved he could use the threat of default to squeeze concessions out of a Democratic president − even though his party controls just one legislative chamber, and by a slim majority at that.

The outcome, which capped weeks of uncertainty whether the U.S. would run out of money, has Democrats, legal scholars and others worried about debt-ceiling standoffs becoming the norm to set partisan policy.

Biden has vowed to explore challenging the constitutionally of the debt ceiling in the months ahead while Democrats in Congress hope to eliminate it legislatively. But legal experts said Biden's push is problematic now that a default was averted and a legislative answer is unlikely in a divided Congress.

"The process sets an extremely dangerous precedent," said Rep. Pramila Jayapal, D-Wash., chair of the House Progressive Caucus, who voted against the debt ceiling deal along with most of her caucus members. "Republicans can hold the economy hostage, they can force through their extremist policy priorities that have absolutely nothing to do with cutting spending or cutting the deficit."

'We used the power we had': How McCarthy got Biden to negotiate

For months, Biden said he would not negotiate with McCarthy over raising the debt ceiling, pushing for a "clean" increase with no conditions to avert a default, like past Congresses have done many times before to ensure the U.S. can fulfill its spending obligations.

The White House banked on spending cuts proposed by Republicans being so unpopular that five or more House Republicans would eventually join Democrats to pass a clean debt ceiling bill.

But a major turning point came April 26 when the Republican-controlled House passed their own debt ceiling bill with more than $4 trillion in spending cuts that also sought to eliminate Biden's core climate and economic policies. House Republican proved they were united. The White House lost its leverage. And Biden soon started negotiating budget priorities.

"We used the power we had to force the president to negotiate," McCarthy said during a floor speech Wednesday before the House approved the deal he reached with Biden.

Democrats forced to vote for 'objectionable' bill

The "Fiscal Responsibility Act" passed the House by a wide 314-117 margin, with strong majorities from both parties, and the Senate by a comfortable 63-36 vote.

More Democrats than Republicans in both chambers voted for the bill. Democrats held their noses to vote for a bill with provisions they oppose, saying their goal was to avoid an economic crisis.

"While I find this legislation objectionable, it will avert unprecedented default, which would bring devastation to America's families," said Rep. Nancy Pelosi, the former Democratic House speaker form California.

McCarthy, addressing reporters after the House vote, was more than pleased to watch Democrats vote for policies they don't like.

"I think it's wonderful they voted for it because they are now on record," McCarthy said. "So they can't sit there and yell this isn't good."

Are we in store for another debt-ceiling standoff?

The debt-ceiling bill suspends the limit on how much the federal government can borrow through the end of 2024, punting the next action on the debt ceiling until after the presidential election.

If Biden wins reelection and Democrats reclaim control of the House and win back the Senate, this year's brinkmanship on the debt ceiling would be avoided. But a divided legislative branch with Biden still in the White House could be the recipe for a debt-ceiling repeat.

There's also this scenario: Biden loses the presidency but Democrats win either the House or Senate. Could Democrats then use their leverage in the next Congress to pursue their policy demands as part of a debt-ceiling deal? Atop their priorities could be rolling back former President Donald Trump's tax cuts for corporations and wealthy Americans.

"By weaponizing the debt ceiling, Republicans are establishing a precedent that will haunt us forever," said Rep. Jim McGovern, D-Mass., "That one party can use the full faith and credit of the United states as a hostage to pass their widely unpopular ideas that they could not get done through the normal legislative process. It is a lousy, lousy, way to govern."

Biden wants to explore 14th Amendment to avoid future debt-ceiling standoffs

Throughout the weeks-long debt-ceiling standoff, Biden said he was considering invoking the 14th Amendment to bypass Congress and get around the debt ceiling, which sets a cap on the amount the U.S. can borrow.

During a low point in negotiations with McCarthy, Biden said flatly that he believes he has the authority to prevent a default unilaterally because of the 14th Amendment, which says “the validity of the public debt of the United States … shall not be questioned.”

Although he ultimately reached a deal with House Republicans, Biden on multiple occasions said he wants to explore taking the 14th Amendment argument to court to challenge the debt ceiling.

"I’ll be very blunt with you: When we get by this, I’m thinking about taking a look at − months down the road − to see whether, what the court would say," Biden said on May 9. After reaching a tentative deal with McCarthy, Biden last Sunday said he wants to see "whether or not you need to reduce the debt limit every year."

"But that's another day," Biden added.

Legal experts question Biden's strategy

Helping advise Biden on the 14th Amendment was Laurence Tribe, professor emeritus at Harvard Law School and constitutional law scholar, who changed his mind on the legal theory after dismissing it in 2011 when President Barack Obama faced the risk of default.

Had Congress not taken action before the June 5 date for default, Tribe said the 14th Amendment would have "imposed a duty" on Biden to ensure the Treasury meets its financial obligations.

Yet Tribe and other legal experts said Biden's quest for an answer from a court before the next debt-ceiling crisis is unrealistic without a looming default as grounds to challenge the statute.

"It would be very problematic," Tribe said. "It's clear that at the moment of crisis, it's too late to test it. And it's clear that at a time like this, when the debt ceiling is not hanging over us, it's too soon to test it."

Garrett Epps, a constitutional law professor from the University of Oregon, also questioned Biden's strategy. "This has been puzzling me ever since he said it," Epps, who backs the 14th Amendment theory, said. "If there's no default, then where's the case?"

Epps said Republicans, in essence, demanded concessions from the Biden administration by "threatening to violate the Constitution" by not paying off U.S. debts.

"I think the problem is that he's now normalized this kind of brinksmanship," Epps said of Biden. "And I fear that Biden's response was sufficiently gormless that this will happen again in two years."

Tribe said the 14th Amendment will have to be explored "outside the courts" by the Department of Justice's Office of Legal Counsel, the White House Counsel's Office and the Congressional Research Service.

"It's not ideal. It's not going to lead to a resolution that everyone agrees with," Tribe said. "But we have to at least begin the dialogue. We can't just say, well, we got past that crisis, now we can forget about it."

Reach Joey Garrison on Twitter @joeygarrison.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Will debt ceiling standoffs become the new norm?