This deadly disease that kills deer and elk has been detected in California for the first time

A deadly disease that has ravaged deer in other parts of North America was found for the first time in California this week.

According to the state Department of Fish and Wildlife, chronic wasting disease was detected in two deer after samples were examined Monday, marking the first time the fatal disease has been found in deer or elk in the state.

The samples came from one deer that was found dead from unknown causes near Yosemite Lakes in Madera County and another deer that was struck and killed by a vehicle near Bishop in Inyo County.

“The disparate locations of these two detections indicate that CWD has probably been present in California for some time, since the incubation period can be months to years,” state wildlife officials said in their announcement Tuesday. Experts said the disease can take as many as two years to develop once an animal is exposed. Once infected, the disease is fatal.

Chronic wasting disease, sometimes known as “zombie deer disease,” is a contagious infection similar to bovine spongiform encephalopathy, better known as mad cow disease, that attacks the nervous system and disproportionately affects deer, elk and moose in the wild and captivity.

It does not affect humans, global health officials say, though experts say keeping it out of the food chain is a priority.

Stopping spread, eliminating disease is challenging

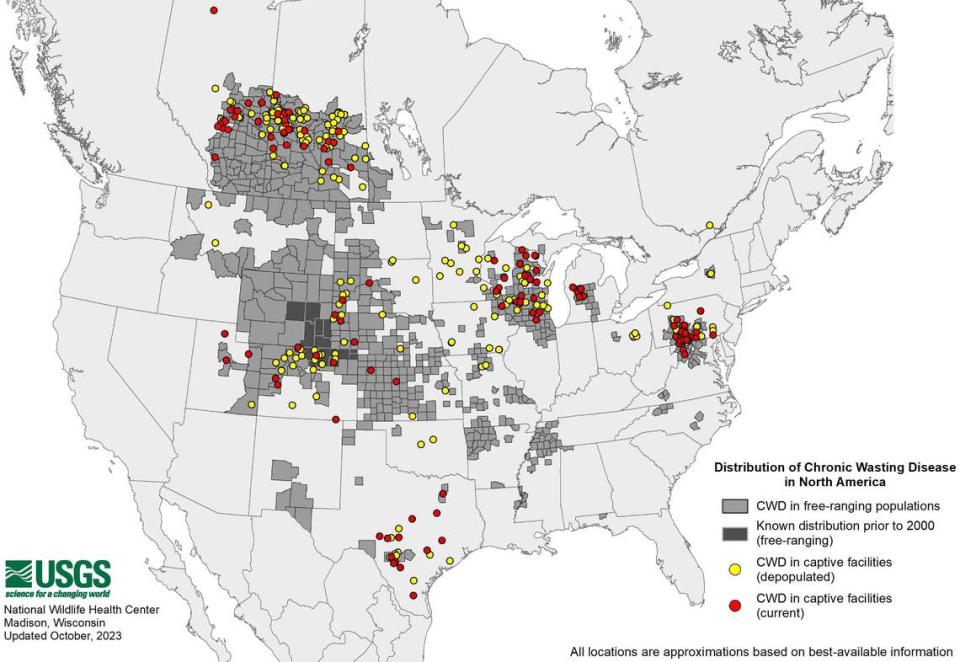

Since its discovery in 1967 in a Colorado herd, the disease has been found in 34 states and five Canadian provinces. Officials said the disease had been detected in California previously, though not in deer or elk.

If left unchecked, the disease could decimate black-tail and mule herds along the Sierra Nevada foothills or reach the coastal prairie mountains — areas where many of the state’s half-million deer live, according to the latest population estimates in 2017.

Signs of the disease among animals include weight loss, clumsy movements, drooling, excessive thirst, urination and behavioral changes.

Unlike mad cow disease, where cattle are often infected in closer quarters, the disease has stumped scientists for most of its existence as deer, elk and moose — members of the cervid family — are mostly solitary in the wild. Scientists believe the most common transmission comes from soils that are contaminated by the excrement of infected animals; the abnormal proteins, scientists suggest, can endure for a decade or more after being shed.

Combating the disease also has been difficult.

New York is the only known state to have eliminated the disease through early culling of infected populations, according to The New York Times. Officials in Quebec slaughtered as many as 3,500 animals after a September 2018 detection at a managed operation, which had to be shut down, though the disease is still found in the province.

The latest outbreak, another first, was detected in British Columbia in two deer samples and has since prompted mandatory testing for deer hunted in specific zones.

What state officials are doing to find disease

For its part, California wildlife officials have been on guard against the disease, monitoring and testing California elk and deer populations since 2000. The state has carried out more than 6,500 tests and has been working with hunters, taxidermists and meat processors to improve surveillance in recent years.

A dashboard produced by CDFW shows which hunting zones have had tests over the years, as well as how the samples were obtained. The dashboard also shows a red 10-mile radius around each positive sample’s origin.

Dr. Brandon Munk, a wildlife veterinarian for the state, said infected animals can transfer the disease easily and “these prions can persist in the environment for years, making it very difficult to prevent or control the spread once it has been introduced.

“The public can help limit the spread of CWD by reporting any signs of illness in deer and elk populations, and hunters should strongly consider testing their harvested deer or elk.”

Those who encounter sick deer or elk can report it to the department via web form.