Death tally after rotenone dose in Miramichi watershed: 32 smallmouth bass, 514 salmon

A progress report on the use of rotenone in the Miramichi River watershed to protect Atlantic salmon from an invasive species, says the first application killed 32 smallmouth bass, the targeted fish, and 514 salmon, most of them juveniles.

A spokesperson for the group applying the rotenone, however, suggests people not read too much into the lopsided death toll.

The Working Group on Smallmouth Bass Eradication in the Miramichi was required to submit the report to the Department of Fisheries and Oceans as part of its permit to put rotenone — used as an insecticide, and pesticide and piscicide — in the water last fall.

The report, dated Dec. 15, 2022, details the rotenone application on Lake Brook and 15 kilometres of the Southwest Miramichi River on Sept. 8, 2022, which the group calls "phase one."

Neville Crabbe, the only person allowed to speak for the working group, said there was no expectation that more bass, a predator that feeds on young salmon and salmon resources, would be killed than any other fish.

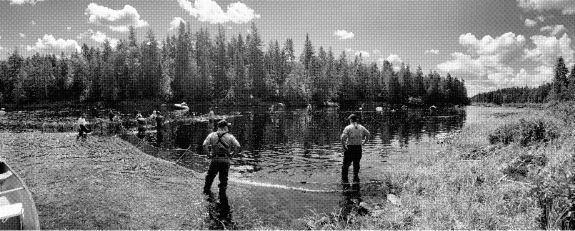

A photo from the report of crews setting up a net to rescue Atlantic salmon before rotenone is applied. (Miramichi Smallmouth Bass Eradication Project 3-Month Post Application Report)

"They're an invasive species that are new to that part of the ecosystem, and the numbers really are not significant to any degree," Crabbe said Thursday. "The threat exists if you have four smallmouths or 4,000."

"I think even DFO would tell you the same thing that there's kind of nothing there with the numbers."

When asked if the treatment was successful, Crabbe said yes.

But he added that success for the group will be the full eradication of smallmouth bass from the watershed, including Miramichi Lake, which has not yet been treated with rotenone.

"And having been prevented to this point from completing our project, we can't achieve that metric of success," Crabbe said.

The working group has been trying to spray Miramichi Lake since summer 2021 but has been blocked by Wolastoqey women paddling on the lake to prevent spraying as well as by legal actions. Cottagers on the lake have spoken out against the spraying, which proponents said would kill all aquatic life, not just the bass.

Crabbe would not say whether a second application would be tried this year, but said Thursday that a "substantial announcement" could be expected soon after much discussion among group members.

CBC News obtained the progress report from the Department of Fisheries and Oceans through a freedom of information request after Crabbe did not respond to queries during the summer.

DFO spokesperson Paulette Hall said Thursday that as an invasive species, smallmouth bass are not yet prevalent or established, "and that explains why the post-treatment results are much higher for those native fish than for the targeted species of the treatment."

Neville Crabbe, spokesperson for the Working Group on Smallmouth Bass Eradication in the Miramichi, says the lopsided numbers of dead fish are to be expected because the smallmouth are still new to the watershed and haven't taken over yet. (Shane Fowler/CBC)

When DFO is authorizing a project, Hall said, it takes into account the overall benefit for the river against the negative impacts on native species.

"That's what we would have considered a success, and that's why we issued that authorization," Hall said.

She agreed it is "very difficult" to establish a count of the population of smallmouth bass in the river or lake, but there "certainly" is a higher population of bass in Miramichi Lake.

The species does not migrate, she said, but when a population grows too large, such as in Miramichi Lake, the fish will start to spread to other areas, such as the river section that was treated with rotenone last fall.

A document put together by Crabbe's group and shared in the summer includes a chart on catch data for smallmouth bass in the lake. The last year of data is for 2021 and lists 1,591 catches in the lake. There are no similar figures for salmon.

The progress report also monitored the rotenone present in the water, which it says had lowered to undetectable levels 60 hours after treatment.

Future of Miramichi Lake treatment not clear

Hall said DFO had "not received any application for an authorization" to spray Miramichi Lake as phase two. "You cannot jump to a conclusion" that phase two would automatically be approved, she said, and fisheries officials will do a full evaluation on any phase two proposal.

Hall noted that since last year's application was done in September, "I would have expected if someone wanted to do that project [now], that we would be working on that application as we speak, if not earlier."

"It's not something that you would decide overnight."

Quantification of dead fish 'not relevant,' group says

The group's permit required a "fish migration barrier" approximately 80 metres long, and it was erected July 25, 2022, downstream from the treatment area. On July 27 and 28 last year, a "fish rescue" was conducted to relocate salmon before the treatment occurred, which saved 51 adult salmon, according to the progress report.

The barrier was also used to catch and count dead fish after treatment. A table in the report details catches at the barrier of eight different species killed by the rotenone.

An 80-metre-long "fish migration barrier" was installed downstream from the Rotenone treatment area, as seen in a photo in the progress report. It was to prevent fish from swimming up into the area, but also to collect dead fish killed by the rotenone and count them. (Miramichi Smallmouth Bass Eradication Project 3-Month Post Eradication Report)

The highest toll was on salmon. The 514 killed included 504 parr, the juvenile stage of the fish.

Hall said most populations have more juveniles than adults and many of them will not survive to adulthood.

"Essentially that's why we would have the larger numbers of younger fish that will be killed by a treatment."

An asterisk under the report's number for smallmouth bass deaths adds that 15 additional dead smallmouth were collected farther downriver, but does not say how many salmon or other species were also caught downriver.

The table from the progress report showing the different species of dead fish collected from the barrier across the river downstream of the rotenone application. (Miramichi Smallmouth Bass Eradication Project 3-Month Post Application Report)

The report says that because the barrier was 4.5 kilometres from the treatment, not all dead fish floated down as far as the barrier.

"Fish were observed within the treatment area lodged against rocks or settled out in the river bottom in slow moving areas, where they decomposed or were scavenged," the report says.

The report does not quantify in any way the additional bass, or salmon, observed decomposing in the river.

Crabbe said based on his observations from the treatment, he estimates only a "small percentage of smallmouth" of the total population were affected.

Expert weighs conservation against salmon deaths

Krish Thappar, a recent master student graduate from Dalhousie University's Marine Affairs program, wrote his graduate project on freshwater species eradication methods such as electrofishing, scientific angling and what he called "more debatable" approaches such as rotenone.

"There's no easy answer when it comes to aquatic species management," Thappar said, adding that determining which method to use has to happen on a case-by-case basis, evaluating the invasive species, size of the habitat they occupy, if the water is landlocked or connected to more ecosystems.

Krish Thappar graduated from Dalhousie's Marine Affairs master's program and studies aquatic invasive species management. He said the use of rotenone had to be looked at on a case-by-case basis. (Krish Thappar/submitted)

"When you want to apply rotenone, you pretty much want to cut all ties, you want to remove all the fish," Thappar said. "But unfortunately, that comes with a price."

When the public sees the data on species killed it can be "quite striking," Thappar said. Before he got into researching rotenone, he was "quite shocked" seeing the numbers himself.

"But at the same time, it's often hard and I struggle with that too personally, looking overall at the long-term objective: what are we trying to achieve? Full eradication."