After decades as a medical skeleton, a hanged Black man's remains will be given proper burial

The remains of a Black man hanged for murder in Nova Scotia nearly 200 years ago will be laid to rest Saturday after his skeleton spent decades on display in doctors' offices.

Labban Powell, who lived in Cornwallis Township, was hanged in a public execution near Kentville after being convicted for the murder of a white man in 1826.

His body was claimed by a physician at the time — as was legal if no family came forward — to be used to train medical students.

Powell was buried near an anthill. When only his bones remained, the doctor placed them in his office to help educate patients — as is done with plastic skeletons in modern times.

"Every human being has worth, and I just feel that he was — his remains — were treated in such a way, desecrated almost, the way that he was treated," Rev. Rhonda Britton, told CBC Radio's Information Morning Halifax.

"I feel it's important to lay these remains to rest in a dignified manner."

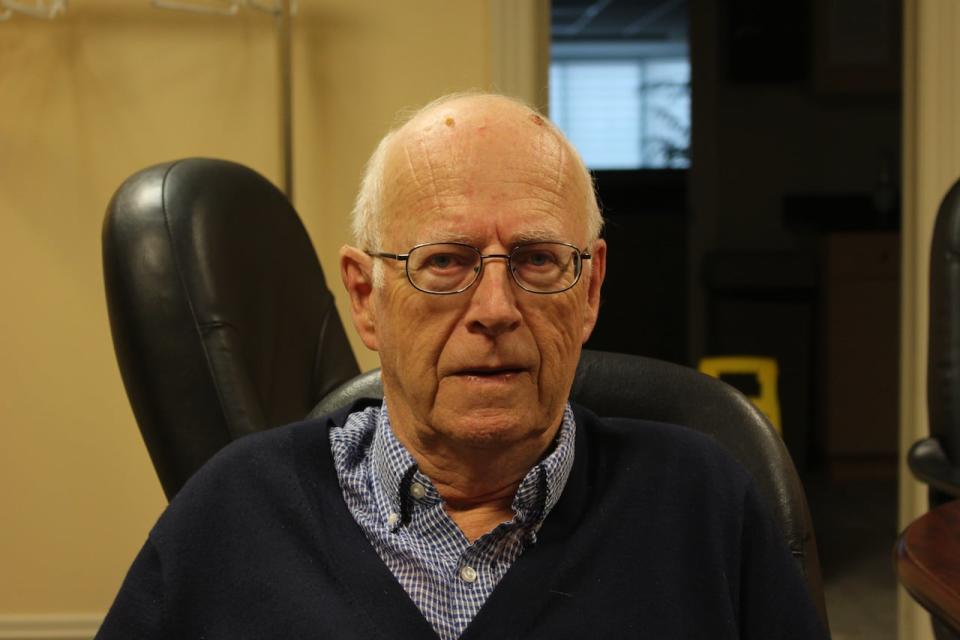

Rev. Rhonda Britton, the pastor of New Horizons Baptist Church in Halifax, will lead the ceremony on Saturday. (CBC)

Britton, the pastor at New Horizons Baptist Church in Halifax, will be leading a ceremony and burial for Powell at the Gibson Woods United Baptist Church, at 1 p.m. AT.

She said officials with the church in Gibson Woods, a historically Black community north of Kentville, agreed to host the ceremony and bury Powell's remains on the property.

Passed through generations

Powell's story — and bones — were brought to Britton and the Gibson Woods church by Allan Marble, the chair of the Medical History Society of Nova Scotia.

Marble said the society came into possession of the bones about 20 years ago, when Dr. David Webster of Yarmouth donated a large collection of historical medical paraphernalia.

The collection, which included the bones, had been passed down through several generations of doctors in the Webster family.

Allan Marble is the chair of the Medical History Society of Nova Scotia. (Moira Donovan/CBC)

Marble said the bones were loose inside a bag when they were donated. Some were missing, including the skull.

"That was the way it was for about 17 years … we knew that they were human bones, but we didn't know who they belonged to," he said.

But that mystery was solved in 2022, when Marble discovered a letter written by Dr. Charles Webster, Dr. David Webster's grandfather.

Marble said the letter detailed how Dr. William Webster, Charles's great uncle, attended the hanging of a Black man convicted for murder in Kentville in July 1826.

The remains of Labban Powell will be laid to rest in the cemetery of the Gibson Woods United Baptist Church. (Cristian Monetta/CBC)

However, he is not the doctor who claimed Powell's body. Webster actually stole them from the doctor who did claim the body, Marble said.

The story goes that once the bones were cleaned, bleached and placed in this doctor's office, Webster snuck in and stole them, hiding them inside the deep pockets of a cloak so he could display them in his own office.

"Now you would almost think that [the doctor] would go and try to retrieve [the skeleton] but there's no evidence that he did, so it's one of those strange little stories that is probably true but we don't have any first-hand evidence of it," Marble said.

Finding a name

Marble said he was able to put a name to the bones after reading the diary entry of a young woman named Mary Norris who had attended the hanging of a Black man named Labban Powell in July 1826, and comparing that to Nova Scotia Supreme Court records.

He said once the society had a name to go with the bones, it was only right to ensure they had a proper burial.

"It's not right in our view that we should be harbouring someone's bones since we know their name …. so that's the reason we made the decision that they should be given to the community where the man came from," Marble said.

Britton agrees, but she still has questions about the circumstances of Powell's death.

She pointed to an excerpt from A History of Law in Canada Volume 1 by Philip Gerard, Jim Phillips and R. Blake Brown that reads:

When Laban Powell, a Black resident of Cornwallis, Kings County, got into an argument with a fellow resident of a boarding house in 1826 and killed him, the jury took no time to convict when the Supreme Court circuit came around to Horton in that county a few months later.

More importantly, practically no consideration was given to whether he should be pardoned or executed, either by the trial judge or the council. As Chief Justice Blowers told Lieutenant Governor Sir James Kempt, 'The sooner the sentence is carried into execution the more striking will be the example' set.

Not surprisingly the council rapidly concluded that it could not recommend mercy. A white perpetrator may have ultimately suffered the same fate, but much more would have been said before that conclusion was arrived at.

Britton said many details of the altercation aren't known, like if it was an accident, if Powell was acting in self-defence or if he was represented by counsel.

"At the end of it all, we can't change what has happened," she said.

"But what we can do is we can certainly remember him and give him the human dignity that he deserves, any person deserves, regardless of what they've done in this life."

Britton said Saturday's service is open to the public, and she's hopeful Powell's descendants will attend.

For more stories about the experiences of Black Canadians — from anti-Black racism to success stories within the Black community — check out Being Black in Canada, a CBC project Black Canadians can be proud of. You can read more stories here.

(CBC)

MORE TOP STORIES