DeSantis appointed over 300 people to important state posts. There are some patterns

Gov. Ron DeSantis has made fighting the influence of the federal bureaucracy central to his campaign for president.

“We’ll bring the administrative state to heel,” DeSantis vowed during his campaign launch on Twitter in May. Since then, he’s promised to make sweeping changes to the Department of Justice, which he says has been too aggressive in its pursuit of conservatives like former President Donald Trump.

If elected, he’d have his work cut out for him. Every four years, Congress publishes a report on government positions that are subject to appointment. In 2020, that report listed more than 9,000 positions — a staggering reminder of the scale of the executive branch.

To understand how DeSantis might carry out that work — and what kind of people he might appoint to those positions — the Tampa Bay Times reviewed the most recent appointments DeSantis made to state agencies and boards large and small, obscure and prominent.

The review covered 309 appointments for 96 boards and agency positions that were brought before the Florida Senate for confirmation earlier this year. (Hundreds more appointments were not subject to Senate oversight, and the Times didn’t examine appointments from years past, or recent appointments not brought before the Senate this year.)

The review noted DeSantis’ penchant for appointing news-making, polarizing figures to both high- and low-profile positions.

But it also found that one in four of his appointees had been chosen by a previous governor and were reappointed to the role by DeSantis.

People familiar with government work

In many instances, DeSantis relied on seasoned movers and shakers who’ve run in government circles for years. Some of the governor’s picks interviewed by the Times said they’ve never heard from DeSantis himself about their appointment. At least half a dozen of his picks donated to DeSantis’ Republican primary opponent, Adam Putnam, in the 2018 governor’s race.

Federal appointments are also fundamentally different from many state board executives. Although they serve important regulatory functions, those who sit on professional boards in Florida, such as the Board of Chiropractic Medicine, are often not paid, or are minimally compensated.

Still, the picks show how DeSantis has continued Florida’s decades-long journey of conservative governance.

DeSantis’ office did not respond to emailed requests for comment on this story.

But Trump, DeSantis’ chief rival for the 2024 Republican presidential nomination, recently criticized DeSantis in an emailed statement to reporters, saying the governor had a “history of terrible appointments,” including some that were not included in the Times review.

For example, Trump slammed DeSantis for picking a secretary of state, Michael Ertel, who resigned in 2019, just weeks into his tenure, after pictures of him wearing blackface at a Halloween party surfaced.

Who is DeSantis picking?

The vast majority of DeSantis’ picks reviewed by the Times were registered Republicans. Nearly three in four of the picks were men. At least one in five had donated to the governor. (The governor’s office did not respond to requests for a more detailed demographic breakdown of DeSantis’ picks.)

And, in a sign of how DeSantis is reaping the rewards of a Republican supermajority in Tallahassee, which he probably won’t enjoy in Washington, nearly all of his picks got the official OK from lawmakers.

The Florida Senate considered 298 of the 309 picks analyzed by the Times this year. Every appointee who got a floor hearing — from DeSantis’ closely-watched picks to oversee Disney’s special tax district to his choices for the less newsy Florida Board of Funeral, Cemetery, and Consumer Services — got confirmed.

That includes Craig Mateer, who DeSantis tapped to serve on the prestigious Board of Governors of the state university system. The Orlando-area entrepreneur had given DeSantis’ political committee $300,000 over the years and would go on to give the governor $100,000 more last year.

The state’s university system has been central to DeSantis’ push to remake Florida’s schools. For example, the Board of Governors in March voted to require faculty members to undergo tenure evaluations every five years.

The Senate also unanimously confirmed seven of DeSantis’ picks for the Board of Medicine, and four of his choices for the Board of Osteopathic Medicine this past session.

Those boards each voted in recent months to ban certain medical treatments for transgender youth — acting against the recommendation of several prominent health groups, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, in order to enact a key policy priority of the governor.

Nikki Whiting, a spokesperson for the Florida Department of Health, which works closely with these medical boards, said DeSantis’ picks aren’t partisan.

“These folks, regardless of party affiliation, are there because of their expertise,” Whiting said.

DeSantis’ most controversial picks

With hundreds of seats needing to be filled each year, it isn’t feasible for the governor to choose only friends and allies, say those involved in the process.

“How many friends can you pick when you appoint thousands of people?” said Ed Moore, whom DeSantis put on the Commission on Ethics in August. As a former legislative staffer who’s been around Florida government for decades, Moore said he knows firsthand that it’s not easy to find dedicated, qualified people.

Moore has donated about $4,500 to DeSantis over the years. But he was not a true believer on Day 1: Moore originally supported Putnam in the 2018 governor’s race.

“A good governor is going to try to bring in people of different perspectives,” Moore said.

Still, DeSantis has also appointed ideologues and loyalists to several key positions.

He made national news for choosing conservative scholar Christopher Rufo to serve on the New College Board of Trustees.

Esther Byrd, whom DeSantis tapped to serve on the Board of Education, drew criticism after online posts surfaced of her defending the Proud Boys extremist group and for being photographed on a boat flying a flag emblazoned with a logo associated with the QAnon conspiracy theory. (Byrd was confirmed by the Senate with just one lawmaker voting against her.)

Her husband, former state Rep. Cord Byrd, was confirmed again this year as DeSantis’ secretary of state — the state’s top elections official.

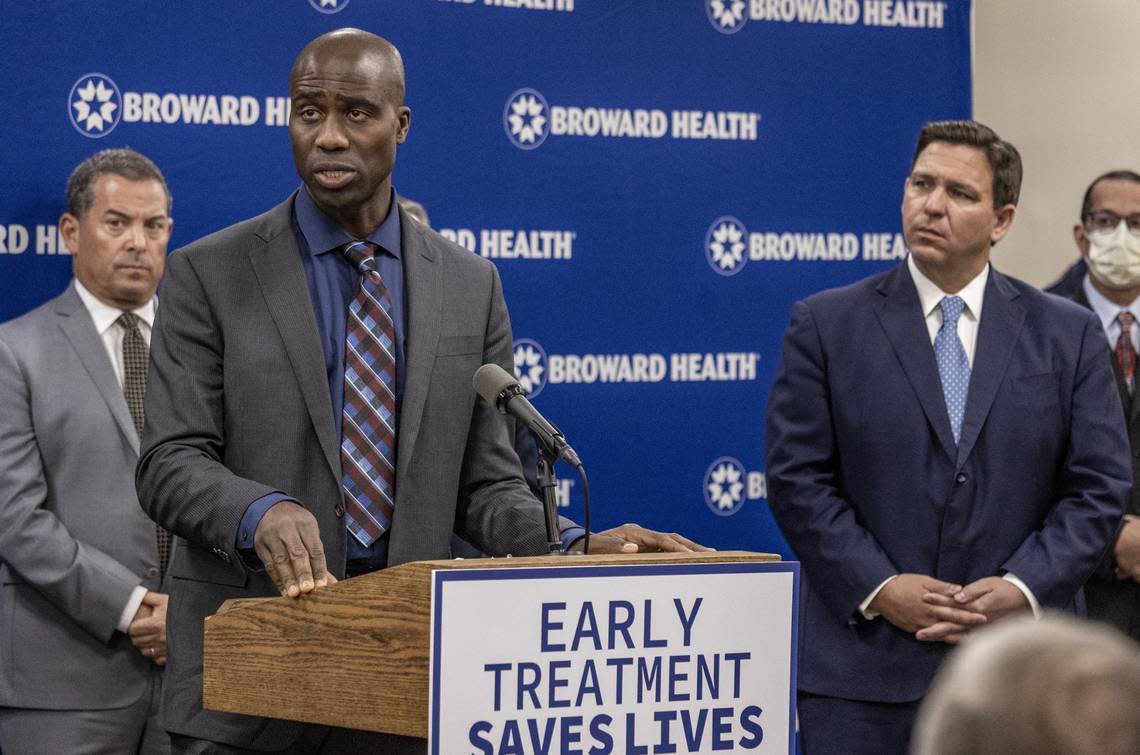

Joseph Ladapo, the state’s surgeon general, has also been polarizing for Florida lawmakers and others. While the coronavirus raged in Florida, he declined to wear a mask inside the office of a state senator who was undergoing cancer treatment, despite the senator’s request that he do so.

Ladapo also oversaw and publicized a Department of Health study warning young men not to get mRNA COVID-19 shots. The study omitted data that went against the department’s anti-mRNA vaccine recommendation.

His initial appointment was met with such stiff partisan resistance that Senate Democrats walked out of the 2022 confirmation hearing. (He was confirmed this year by a vote of 27 to 12.)

Even some of DeSantis’ picks for lesser-known positions have at times drawn attention.

Sandra Atkinson, an Okaloosa County Republican who DeSantis picked to serve on the Board of Massage Therapy in 2021, reportedly entered the U.S. Capitol during the riots on Jan. 6, 2021, according to an investigation by USA Today.

However, the Senate did not consider her appointment in 2022, and she left the massage board in March 2022. She was not a part of the Times analysis.

Filling vacancies

One of DeSantis’ major environmental moves, which came just days into his first term, had to do with executive appointments.

In a nearly unprecedented step, DeSantis in January 2019 asked every member of the governor-appointed South Florida Water Management District to resign. By March, he had filled that board with his own picks.

The turnover came largely in response to the board’s decision to approve a sugar company land lease near the Everglades which DeSantis questioned. It was a sign of one of the truisms of DeSantis’ time in the governor’s mansion: When he sets his mind to something, it often happens.

But DeSantis has at times been slow to move on some appointments. In August 2020, Florida was in the middle of the coronavirus pandemic. Executive appointments to regional water boards had fallen off of DeSantis’ priority list.

So much so that an environmental group sent a letter to the governor warning that three of the state’s five boards would soon be unable to field a quorum if DeSantis did not appoint more members to those bodies, as required by law.

Later that fall, DeSantis made several appointments to the water district boards, and they began to function again more or less as normal.

The Times’ analysis of the governor’s appointments did not find many boards with large numbers of vacancies that could hobble their ability to perform.

Darrick D. McGhee Sr., whom DeSantis reappointed in October to another term on the Florida Commission on Human Rights, said the governor actually solved his board’s attendance problem. Before he was originally appointed in 2020, the commission, which mediates civil rights-related cases, was unable to meet because it was short of appointees.

DeSantis filled the board, and it has since cleared its backlog of cases, McGhee said.