Are Dinosaurs Real? What We Know About the Extinct Creatures

Are dinosaurs real? Most people don't have to travel too far to answer that question in the affirmative with some kind of exhibit displaying dinosaur fossils. In addition to touring shows, there are museums all over the world teeming with artifacts supporting the existence of sauropod dinosaurs and other dino peers.

But if you want to get a really good look at a dinosaur, you may not have to travel at all. Simply look at any bird you can see outside your home.

Are Birds Dinosaurs?

The prevailing scientific view is that whether you see a hummingbird, a robin, a flamingo or an ostrich, you see a descendant of dinosaurs. Some scientists go so far as to call birds avian dinosaurs and all other dinosaurs non-avian dinosaurs.

The thought that a giant carnivore like Tyrannosaurus rex has something in common with an ordinary wren might seem far-fetched, especially since people often describe dinosaurs as reptiles. But the idea that dinosaurs became birds has been around for more than 100 years.

In 1868, Thomas Henry Huxley described evidence that birds evolved from dinosaurs. This is currently the most widely-held scientific theory about the origin of birds, and it's helped shape today's view of dinosaurs as swift and agile instead of plodding and clumsy.

How We Know Extinct Dinosaurs Existed

To learn about dinosaurs, researchers have to study physical clues and put these clues into the context of current scientific knowledge. This can be a tricky process.

There were no humans on Earth when dinosaurs lived, so there are no written records or illustrations of how they behaved or what they looked like. All we have are:

Bone and egg fossils

Collections of footprints called trackways

Our knowledge of living animals

Dinosaur Facts

Dinosaurs were a group of land animals that lived from about 230 million years ago until about 60 million years ago. This spans the era of the Earth's history known as the Mesozoic era, which includes, from most ancient to most recent, the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous periods.

Dinosaurs grew in population and diversity during their time on Earth before becoming extinct at the end of the Cretaceous period.

No one knows precisely how many types of dinosaurs inhabited the planet. There are currently about 700 named species, but this probably represents a fraction of the dinosaurs that ever existed.

Dinosaurs ranged in size from immense to tiny, and they came in various shapes. Today's dinosaur classifications come from these differences in shape and size.

Carnivorous dinosaurs were all theropods, bipedal animals with three-toed feet. Carnosaurs were a small, agile type of theropod. One of the most widely-known carnosaurs was the Velociraptor, which is considerably smaller than depicted in the "Jurassic Park" films.

Sauropods, on the other hand, were enormous, four-legged herbivores like Brachiosaurus, Apatosaurus and Diplodocus. Dinosaurs with armored bodies and spiny tails were ankylosaurs. Ceratopsians — like Triceratops — had frills and horns on their heads.

Dinosaur Traits

But not every reptile that lived during the Mesozoic era was a dinosaur. Many extinct animals that people think of as dinosaurs aren't actually dinosaurs because they don't share one or more of the dinosaurs' basic traits:

Dinosaurs were animals with four limbs, although not all walked on all four legs.

Although they may have ventured into the water, they were terrestrial, or land-dwelling, animals.

Their muscles and bones had several specific features. For example, all dinosaurs had cheek muscles that extended from their jaws to the tops of their skulls.

Their hip girdles comprised three bones — the ilium, ischium and pubis. These bones fit together in one of two configurations: ornithischian (bird-hipped) or saurischian (lizard-hipped).

They had an upright gait. Dinosaurs held their bodies over their legs like rhinoceroses do, rather than using the sprawling gait that crocodiles do.

Non-dinosaur Prehistoric Animals

These traits keep some well-known prehistoric animals from being considered dinosaurs:

Plesiosaurs were aquatic creatures with long bodies and flipper-like fins.

Ichthyosaurs, another aquatic reptile group, had a more dolphin-like body structure.

Pterosaurs, like Pteranodon and the Pterodactyl subgroup, were flying reptiles.

Synapsids had an opening behind their eye socket that also occurs in mammals. One of the most well-known synapsids is Dimetrodon, a lizard-like animal with a large sail on its back.

So because of their bone structure, habitat or other traits, these animals weren't technically dinosaurs. But they did leave behind the same evidence that dinosaurs did: fossilized bones.

The World of Dinosaurs

The earliest dinosaurs lived in a world that looked very different from the Earth we know today. Rather than being separated by expansions of ocean, the continents formed a mass known as Pangea.

Dinosaurs lived for about 170 million years, and during that time, the continents gradually spread to form the shapes we recognize today. (Thanks, plate tectonics!) Dinosaurs continued to live on every continent; there are even fossils buried under the ice in Antarctica.

Dinosaur Appearance: Skin and Bones

When sediment covers an animal's body shortly after death, its bones can fossilize. Soft tissues, like skin, muscles and other organs, decompose. Minerals from the soil make their way into the bone, turning it to stone.

Fossilization doesn't happen very often, so there are gaps in the fossil record — periods of time when conditions weren't right for fossilization.

Assessing Fossils

Researchers remove fossils from sedimentary rock using a range of tools, from picks to paintbrushes, and lots of patience. It's easy to damage fossil evidence during excavation, and many fossils in the same bed can make it hard to decide which bone belonged to which animal.

After excavating a fossil, researchers typically encase it in plaster and ship it to a research facility. There, scientists can make casts, or reproductions, of the bones and try to recreate the complete skeleton. Scientists can learn a lot from this process:

The way the bones fit together gives a basic idea of the dinosaur's shape and posture.

Flat, leaf-shaped teeth mean that the dinosaur ate plants. Sharp, pointed teeth suggest that it ate meat.

The proportions of the leg bones relate to how fast the dinosaur could run.

Cavities in the skull suggest how well it could see and hear.

Bumps called quill barbs on the bones mean the dinosaur had feathers. Some Velociraptor specimens have these barbs.

Technology plays a part, too. Computer simulations help determine how fast a dinosaur could move and how it used its limbs. Researchers can also use computer models to reconstruct the dinosaur digitally, adding virtual layers of muscles, tissue and skin to a 3D skeleton image.

With computerized axial tomography (CAT) or CT scans, scientists can also get a detailed view of inaccessible parts of skulls and other bones.

So, Did Dinosaurs Have Feathers?

The surrounding rock can offer its own clues. There can be impressions from leaves or feathers, fossil eggs or the remains of nests. Impressions from the dinosaur's skin can give paleontologists an idea of its texture.

But none of this can answer a fundamental question about dinosaurs' appearance: What color were they? In everything from movies to play sets, dinosaurs appear in shades of gray, brown and green. But it's just as likely that dinosaurs had the bright coloring of some frogs, snakes and birds.

Determining whether a dinosaur had scales or feathers can also be challenging. The absence of quill barbs doesn't prove that an animal was featherless, and feathers decompose long before bone turns fossil.

However, fossils discovered in China have feather impressions in the surrounding rocks. All this evidence suggests that, in terms of appearance, dinosaurs had some avian traits and some reptilian traits.

Fossil Mummies

Under extremely rare and poorly understood circumstances, a dinosaur's soft tissue can become fossilized. In 1999, Tyler Lyson discovered the remains of a hadrosaur in South Dakota.

The skin and muscle tissue of this fossil, nicknamed Dakota, are intact. CT scans of the preserved body have yielded many new ideas about dinosaurs' bodies and organs. The fossilized skin looks like stone, so scientists don't know what color Dakota was, but patterns on the hadrosaur's body suggest that it had stripes [source: University of Manchester].

Dinosaur Physiology: In Cold (or Warm) Blood

While teeth and bones can offer clues about what dinosaurs ate and how they moved, there are a lot of details we don't know about their physiology. One large question, which encompasses several smaller questions, is whether dinosaurs were warm-blooded like birds and mammals, or cold-blooded like reptiles.

These aren't scientific terms, and they have nothing to do with the actual temperature of an animal's blood. Instead, they describe how an animal uses energy and regulates its body temperature.

A warm-blooded animal controls its body temperature with techniques like sweating and burning stored nutrients. They're endotherms; their heat comes from within. These animals burn energy quickly, or have a relatively high metabolism. They also maintain a fairly consistent temperature, or are homeothermic.

Cold-blooded animals, on the other hand, are ectothermic, meaning they use their environment to regulate their temperature. Many reptiles, for example, raise their temperature by resting in the sun or on warm surfaces. Cold-blooded animals tend to have a relatively low metabolism. They're also poikilothermic; their internal temperatures vary depending on their environment and activity.

So, are dinosaurs homeothermic endotherms, or are they poikilothermic ectotherms? Scientific opinion has shifted through the years.

In the late 1800s, when scientists began theorizing that dinosaurs evolved into birds, people thought dinosaurs must be warm-blooded like their avian relatives. But starting in the 1920s, people began to view dinosaurs as reptiles — and obsolete reptiles at that.

The reasons behind this change are murky and may have been influenced by public opinion. But the idea that dinosaurs were cold-blooded, slow and not very smart began to overshadow the idea that they were intelligent, swift and agile like birds.

Today, the idea that dinosaurs evolved into birds is back in the scientific forefront — but there's ongoing debate about their metabolism. Here's a run-down of some common arguments:

The Case for Endothermic Dinosaurs

Birds evolved from dinosaurs, so they must have inherited their warm-blooded nature from dinosaurs.

Relative to their bodies, dinosaurs' limbs are arranged like mammals' limbs, and mammals are warm-blooded. Computer models suggest that dinosaurs could move very quickly, and, in general, the faster an animal moves, the faster its metabolism tends to be. A CT scan on preserved tissue from a dinosaur skeleton found in South Dakota appeared to reveal that the dinosaur's heart had four chambers, like a bird or mammal, rather than three chambers, like a reptile [source: Fisher].

The Case for Ectothermic Dinosaurs

Extremely large dinosaurs could maintain a constant body temperature through inertia, so they wouldn't need internal body processes to regulate temperature.

The climate during most of the time that dinosaurs existed was warmer than it is today, making endothermic ability unnecessary.

Dinosaurs don't seem to have structures called respiratory turbinates, which are common in endothermic mammals.

Since no one can study dinosaurs in the wild, it's unlikely that scientists will find conclusive proof supporting either argument any time soon.

T. Rex: Scavenger or Predator?

Most people have grown up with the idea that Tyrannosaurus rex was an enormous, aggressive, bloodthirsty predator. However, some scientists argue that T. rex wouldn't have been at all successful as a predator.

Its arms are virtually useless in any hunting scenario, and its body is so large that it could have been fatally injured after a simple fall. Instead, T. rex might have been a scavenger. Its large teeth and jaws may have been devoted to chewing through the bones left from other animals' kills.

Dinosaur Reproduction: Like Birds on Nests

When scientists study dinosaurs, they make inferences, or draw logical conclusions, based on physical evidence and how other life forms behave. One inference is that dinosaurs reproduced sexually and laid eggs. This is logical for several reasons:

Birds and reptiles, dinosaurs' nearest relatives, reproduce sexually.

Birds and reptiles also lay eggs.

N.C. State University researcher Mary Schweitzer discovered a medullary bone in the leg of a Tyrannosaurus rex. Birds use this bone to store extra calcium for egg production [source: Fields].

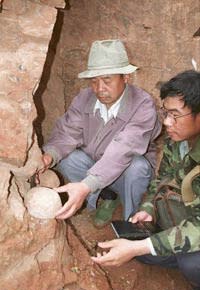

Researchers have found fossilized eggs in locations around the world, and some have dinosaur embryos inside. These eggs seem to be a little different from both reptile and bird eggs, and they have surface patterns that don't appear on any modern eggs.

Matching an egg with its parent is difficult. Researchers have to open lots of eggs to find just one embryo. On top of that, large dinosaurs changed dramatically between hatching from eggs and becoming full-grown, so even a perfect embryo doesn't guarantee a match.

Also, paleontologists have discovered far fewer distinct eggs than species of dinosaurs, so it's possible, though relatively unlikely, that some dinosaurs gave birth to live young.

Dinosaur Nests

But even if an egg's species is unknown, it can still provide insight into how dinosaurs lived. First, like both birds and reptiles, dinosaurs built nests. While some fossil nests are haphazard piles of eggs surrounded by soil and debris, others hold intricately arranged patterns of eggs.

Some excavations have revealed sites with multiple layers of eggs and nests. In some species, dinosaur parents tended their nests carefully and returned to a common nesting ground year after year.

The nests themselves give researchers an idea of how the eggs developed and matured. Some nests are shaped like birds' nests and are higher than the surrounding soil, suggesting that some dinosaurs warmed their eggs just like birds do: by placing their abdomens over the eggs.

While this may sound absurd, researchers have found dinosaur skeletons positioned over their eggs. But not every species did this — others buried and abandoned their nests or, like reptiles, kept eggs warm by covering them with their throat or thorax.

So far, it has been difficult for scientists to determine whether dinosaurs emerged from their eggs ready to fend for themselves, like reptiles, or required extensive parental care, like birds.

A six-year study of 80-million-year-old egg fossils at the University of Leicester determined that at least some species were self-sufficient when they hatched [source: Science]. However, fully-developed embryos from other species were too small or awkward to survive without help.

Dinosaur Reproduction

There's also a lot to be learned about dinosaur reproduction. No one is sure whether dinosaurs exhibited mating rituals or competed for mates.

However, some species appear to be sexually dimorphic; they have different qualities between the sexes. For example, in a ceratopsian species, males might have a bony neck frill that's shaped differently than females' frills.

Dinosaurs clearly had little trouble reproducing, though — they dominated the landscape for more than 100 million years. Humans, on the other hand, have existed for far less than one million years. But in spite of their prevalence, dinosaurs became extinct about 60 million years ago.

Dinosaur Extinction: Waiting for Impact

Dinosaurs became extinct at the K-T boundary — the dividing line between the Cretaceous and Tertiary periods. The end of the Cretaceous marks the end of the dinosaurs, while the beginning of the Tertiary marks the rise of mammal life on Earth.

Dinosaurs aren't the only things that died out at the K-T boundary. About 50 percent of the species on Earth became extinct, including many other large reptiles, like pterosaurs and plesiosaurus, as well as lots of plant species and marine animals.

Other life forms, such as ferns, flourished by taking advantage of the sudden abundance of natural resources.

Dinosaur Extinction Theories

Scientists have proposed several theories to explain dinosaurs' extinction. There's not much physical evidence for some of them.

For example, one theory is that dinosaurs were allergic to flower pollen — flowering plants and bees evolved together during the late Cretaceous period. However, flowering plants existed for millions of years before the dinosaurs died out.

Another theory is that mammals, which began to proliferate at the end of the Cretaceous period, ate dinosaurs' eggs. But considering the number of whole fossil egg specimens, this seems unlikely.

Then there's the Alvarez hypothesis. In 1980, Luis and Walter Alvarez proposed that comets or asteroids had hit the Earth, causing massive shock waves, debris clouds and other devastation. There's a lot of evidence to support this hypothesis.

One is a layer of a mineral called iridium, which exists in many locations on the planet at depths equated with the end of the Cretaceous period. Iridium is more common in space debris than on Earth, so the huge impact of an object from space could have caused this effect.

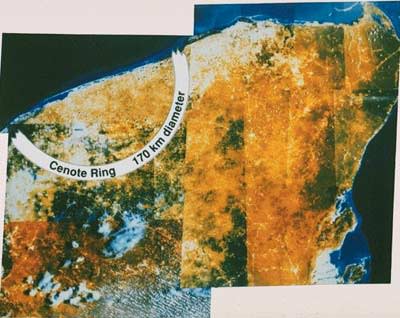

Perhaps the biggest support for this hypothesis is the Chicxulub crater. This is a massive asteroid crater off the coast of the Yucatán Peninsula. Based on measurements of sediments and analysis of the surrounding rock, scientists estimate that the asteroid that caused the crater was between 145 and 180 kilometers (90 to 112 miles) in diameter.

This would have caused exactly the kind of devastation described in the Alvarez hypothesis. A team of three researchers even believes to have discovered the identity of the asteroid itself. Using mathematical models, the group narrowed the field to the Baptistina cluster, a group of asteroids created by a large impact beyond the orbit of Mars [source: Sky & Telescope].

According to the Alvarez theory, the extinction of the dinosaurs was catastrophic and extrinsic, meaning it came from outside of the Earth. However, other theories suggest that the mass extinction was intrinsic and gradual.

One idea is that volcanoes in what is now India experienced massive eruptions just before the end of the Cretaceous. These eruptions filled the air with carbon dioxide and sulfur, changing the climate and damaging plant and animal life.

The changing face of the planet may have also played a role. As the continents moved, ocean currents would have changed the weather patterns in different parts of the world. Various forms of life may have been unable to survive these changes.

The best explanation for what happened to the dinosaurs may be a combination of intrinsic and extrinsic theories — an asteroid impact combined with geological changes and volcanic eruptions. There are also indications that dinosaurs were becoming less diverse before the end of the Cretaceous period.

But regardless of the cause, not everything on Earth died at the K-T boundary. Frogs, mollusks and crocodilians survived, and so did birds.

Birds and Living Dinosaurs

If you have a stubborn, obsolete printer in your home or office, you might refer to it as a dinosaur. You might say the same thing about a politician whose views you consider out-of-date. Or, if you think the latest innovation is doomed to failure, you might say it's going to go the way of the dinosaur.

These figures of speech come from the idea that dinosaurs are a species that died out because they couldn't keep up. They were too big, too slow, too heavy and too old to make it to modern times.

But many scientists don't see it that way at all. Instead of becoming obsolete, dinosaurs evolved into birds, which are extremely sophisticated. Not only did they become a type of animal that still exists today, they also developed a skill that very few life forms on Earth have. Only pterosaurs, insects, bats and birds can fly.

Physical evidence supports the theory that dinosaurs evolved into birds. The first thing to keep in mind is that the theory doesn't apply to every species of dinosaur, or even every subgroup of dinosaur.

The dinosaurs that evolved into birds are theropods, the three-toed dinosaurs that include Tyrannosaurus rex and Velociraptor. Ironically, these are members of the saurischian, or lizard-hipped, subgroup, rather than the ornithischian, or bird-hipped group.

Dinosaur Traits in Birds

Several theropod species have physical features in common with birds. These shared traits are called synapomorphies, and they include:

Wishbones, which are fused collarbones

Hollow bones

Similar hip structures

Today's birds also have fused finger bones at the tips of their wings, which correspond to the claws at the end of dinosaurs' front limbs. We've discussed other similarities already, including feathers and the act of incubating eggs by sitting on a nest. Scientists have even discovered a fossilized skeleton in which the dinosaur's head is tucked under its wing, the same way a duck sleeps [source: Roach].

Of course, this isn't the only explanation for what happened to dinosaurs or for where birds came from. Opponents of the theory of evolution argue that there's no physical evidence for the transition from dinosaur to bird. Dissenting scientists contend that dinosaurs have far more in common with reptiles and are represented instead in today's reptile species, including crocodiles.

Supporters of the dinosaur-to-bird theory reply that Archaeopteryx lithographica, generally regarded as the oldest known bird, partially fills the role of the missing link. Although Archaeopteryx was a bird, it also had lizard-like features, like teeth and a bony tail.

In terms of this theory, more than 10,000 dinosaur species live today.

Today's Theropods

Some modern birds resemble theropods more clearly than robins or sparrows. These include ostriches and emus.

Dinosaur Movies and Myths

Stories about dinosaurs have existed for as long as people have been aware of the existence of trackways and fossils. Some researchers suggest that legends of behemoths and dragons come from the discovery of dinosaur bones and footprints [source: Sanz].

There are also cave paintings that appear to depict bipedal dinosaurs. One team of anthropologists believes that these images were based on both a fossilized skeleton and a set of footprints [source: Ellenberger].

Dinosaur Movies

The first dinosaur movies made their appearance shortly after the development of motion pictures. The earliest dinosaur films came out between 1910 and 1930. One was "The Lost World," which was based on a book by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

Dinosaur cartoons made their debut around the same period. In 1940, Disney released its movie "Fantasia," which used Igor Stravinsky's "The Rite of Spring" as the score for the life and extinction of the dinosaurs.

With the exception of "Fantasia," most of these films depicted humans' encounters with dinosaurs. Characters used time travel to reach the age of the dinosaurs, or they discovered previously unknown locations in which dinosaurs survived.

In today's dinosaur stories, such as "Jurassic Park," DNA plays the primary role in the face-to-face introduction between people and dinosaurs. There are several problems with this idea:

When a dinosaur becomes fossilized, most of its soft tissue decays. The only remaining reservoir for DNA is its bones — and those are physically altered during the fossilization process.

DNA breaks down very quickly. Finding a specimen with its entire DNA sequence intact after millions of years is unlikely.

Although a few researchers have reported finding insect DNA in amber, other scientists haven't been able to replicate the findings.

Retrieving DNA from blood an insect has ingested would be even harder. Even if a mosquito's stomach did hold the blood of a dinosaur, retrieving that blood without contaminating it with the mosquito's own DNA would be next to impossible.

However compelling the argument for preserved DNA might seem, cloning dinosaurs is highly unlikely.

Brontosaurus and Apatosaurus

In the late 1800s, two paleontologists, Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope, had an intense rivalry, which became known as the Great Bone Wars. Both men published reports of new species based on partial skeletons, in part to outdo each other.

In 1877, Marsh discovered part of a spine and pelvis. He named his discovery Apatosaurus ajax. Two years later, he named another incomplete skeleton Brontosaurus excelsius.

In 1903, Elmer Riggs determined that both sets of bones came from the same species. According to the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, the first legitimate name a new species gets is the one it keeps. (You can read the code at the ICZN website.)

News of the name change took a while to spread for several reasons. One was that Marsh made another mistake. He placed the skull of a Camarasaurus, the inspiration for Pleo, on his Brontosaurus body, a mistake proven in the 1970s.

Lots More Information

Related HowStuffWorks Articles

Sources

Current Science. "Who Knew?" Current Science Vol. 93. 11/2/2007.

Deeming, D.C. "Ultrastructrual and Functional Morphology of Eggshells Supports the Idea that Dinosaur Eggs Were Buried in a Substrate." Palaentology. Vol. 49, 2006.

Economist. "A Hop, a Skip and a Jump." Economist vol. 385. 11/10/2007.

Ellenberger, Paul et al. "Bushmen Cave Paintings of Ornithopod Dinosaurs: Paleolithic Trackers Interpret Early Jurassic Footprints." Ichnos. Vol. 12. 2005.

Fields, Helen. "Dinosaur Shocker." Smithsonian Magazine. May 2006. (12/2/2007) http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/10021606.html

Fisher, Paul et al. "Cardiovascular Evidence for an Intermediate or Higher Metabolic Rate in and Ornithischian Dinosaur. Science. Vol. 288. 4/21/2000.

Henderson, Donald M. "Simulated Weathering of Dinosaur Tracks and the Implications for their Characterization." Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. Vol. 43. 2006.

Horner, John R. "Dinosaur Reproduction and Parenting." Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. Vol. 28. 2000.

Hu, Yaoming. "Large Mesozoic Mammals Fed on Young Dinosaurs." Nature. Vol. 433. January 2005.

Lemonick, Michael D. "Dino Conspiracy Theory." Time. Vol. 170. 11/19/2007.

Litwin, Ronald J. et al. "Dinosaurs: Facts and Fiction." USGS. (12/2/2007) http://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/dinosaurs/

Montana State University. "Sept. 9 Paper with MSU Coauthor Underscores Dinosaur Parenting." (12/2/2007) http://www.montana.edu/cpa/news/nwview.php?article=1886

Montana State University. "Sept. 9 paper with MSU coauthor underscores dinosaur parenting" Montana State University. 9/8/2004.

National History Museum, London. "The Search for DNA in Amber." (12/2/2007) http://www.nhm.ac.uk/nature-online/earth/fossils/fathom-dnainamber/assets/12feat_dna_in_amber.pdf

Natural History. "Rethinking Velociraptor." Natural History. Vol. 116. December 2007/January 2008.

New Scientist. "Baby Dinosaur that Crawled Like Us." Vol. 187. 8/6/2005.

Norell, Mark A. and Xing Xu. "Feathered Dinosaurs." Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. Vol. 33. 2005.

Owen, James. "One Size Didn't Fit All for Early Dinosaur, Study Says." National Geographic. 12/15/2007 (12/2/2007) http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2005/12/1215_051215_dino_growth.html

Perkins, Sid. "Deinonychus' claws were hookers, not rippers." Science News. Vol. 172. 11/3/2007.

Perkins, Sid. "Dinosaurs matured sexually while still growing." Science News. Vol. 172. 11/3/2007.

Rees, P. McAllister et al. "Late Jurassic Climes, Vegetation and Dinosaur Distributions." Journal of Geology. Vol. 112. 2004.

Roach, John. "'Sleeping Dragon' Fossil May Link Dinosaurs, Birds." National Geographic. 10/13/2004. (12/2/2007) http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2004/10/1013_041013_sleepy_dino.html

Ruben, John A. et al. "Respiratory and Reproductive Paleophysiology of Dinosaurs and Early Birds." Invited Perspectives in Physiological and Biochemical Zoology. Vol. 76, no. 2. 2003.

Sanz, Jose Luis. "Starring T. Rex!" Indiana University Press. 2002.

Science. "Newly Hatched Dinosaur Babies Hit the Ground Running." Science Vol. 305. 9/3/2004.

Sereno, Paul C. "The Origin and Evolution of Dinosaurs." Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. Vol. 25. 1997.

Sky & Telescope. "The Source of the Dinosaurs' Asteroid." December 2007.

Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. "Anatomy & Evolution." (12/2/2007) http://paleobiology.si.edu/dinosaurs/info/everything/gen_anatomy.html

Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. "General Behavior." (12/2/2007) http://paleobiology.si.edu/dinosaurs/info/everything/behavior.html

Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. "What Is a Dinosaur?" (12/2/2007) http://paleobiology.si.edu/dinosaurs/info/everything/what.html

Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. "Where Did They Live?" (12/2/2007) http://paleobiology.si.edu/dinosaurs/info/everything/where.html

Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. "Why Did They Go Extinct?" (12/2/2007) http://paleobiology.si.edu/dinosaurs/info/everything/why.html

University of California Museum of Paleontology: Berkley. "Are Birds Really Dinosaurs?" (12/2/2007) http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/diapsids/avians.html

University of California Museum of Paleontology: Berkley. "Hot-Blooded or Cold-Blooded"? (12/2/2007) http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/diapsids/metabolism.html

University of California Museum of Paleontology: Berkley. "Othniel Charles Marsh." (12/2/2007) http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/history/marsh.html

University of California Museum of Paleontology: Berkley. "The Dinosauria." (12/2/2007) http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/diapsids/dinosaur.html

University of California Museum of Paleontology: Berkley. "What Killed the Dinosaurs?" (12/2/2007) http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/diapsids/extinction.html

University of Manchester. "Academic Uncovers Holy Grail of Paleontology." University of Manchester press release. 12/3/2007 (12/3/2007). http://www.manchester.ac.uk/aboutus/news/display/?id=128651

Yeoman, Barry. "Schweitzer's Dangerous Discovery." Discover. 4/27/2006. (12/2/2007) http://discovermagazine.com/2006/apr/dinosaur-dna

Original article: Are Dinosaurs Real? What We Know About the Extinct Creatures

Copyright © 2023 HowStuffWorks, a division of InfoSpace Holdings, LLC, a System1 Company