DNA from nearly-forgotten Yukon kokanee salmon 'a treasure' for modern conservation

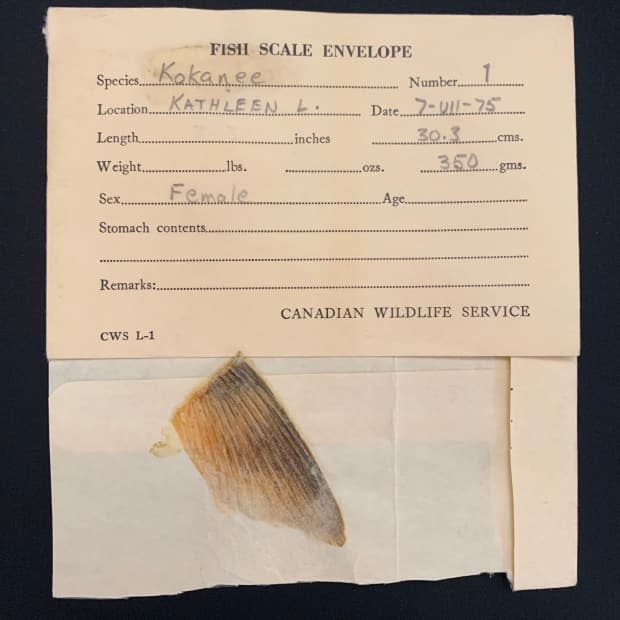

A chance discovery of nearly-forgotten, close to half-century-old kokanee salmon samples from Kluane National Park and Reserve are helping shape present-day conservation efforts.

Using modern techniques, researchers at the University of British Columbia (UBC) Okanagan campus extracted DNA from the historic fin and scale samples, collected as part of routine field work in the 1970s and early '80s, and compared it to recent samples from wild and hatchery-raised kokanee.

The salmon currently in the park's Kathleen Lake system, they found, aren't so genetically different from their ancestors, while the hatchery kokanee had diverged to the point where they shouldn't be reintroduced into the wild.

Kokanee are nearly identical to sockeye salmon save, for the fact that they're land-locked, meaning they don't migrate to the ocean.

The population in the Kathleen Lake system is the northernmost in Canada and is known for its boom-and-bust cycles — since the early 2000s, anywhere between 20 and more than 5,000 fish have returned to their spawning grounds.

Historically, around 3,600 kokanee return to spawn.

Samples uncovered during office move

Carmen Wong, the ecologist team leader for Parks Canada's Yukon branch, said the dramatic swings raised concerns about the population's genetic health.

"When any population goes into decline, you get concerned about the genetic health because you go through bottlenecks," she said.

"There's not a lot of genetic variation potentially coming out the other end when the population rebounds," said Wong.

Low genetic variation can make it harder for a species to adapt to changing conditions, putting their long-term survival at risk.

The historic samples, which Wong happened upon during an office move in 2013, gave researchers an opportunity to compare the DNA from fish before and after the population crashed to see what impact, if any, it had on the kokanee's genetic makeup.

"That's a cool part of the story," Wong said of finding the samples.

"They were just stored quite carefully in a box and kind of forgotten about and then when we were moving offices, I rediscovered this box. And it became a treasure."

The UBC Okanagan team used "genotyping-in-thousands by sequencing" on the historical samples. The relatively new method, developed in the 2010s, allows researchers to target specific snippets within DNA structures where relevant genetic information is found.

While that means the method can be used to quickly process hundreds or thousands of DNA samples at once, the UBC team found it can also be used to process historic DNA, which may be damaged or contaminated, since it only requires a few reference points to produce usable results.

The finding that the kokanee from the 1970s had similar DNA to their modern-day counterparts didn't necessarily allay conservation concerns — they were similar because there was low genetic variation even before the crash.

"That means that that population is resilient, even with low genetic diversity, and it means it can go through a crash and come out somewhat okay," Wong said.

"But the low level of genetic diversity means it doesn't have a lot to deal with, should anything else come its way that it needs to draw upon its genetic resources to (adapt to)."

Concerns over releasing hatchery fish into the wild

Michael Russello, the biology professor at UBC's Okanagan campus who led the DNA research, told CBC News that it was "a little surprising" that the population crash didn't have any "severe genetic consequence" on the kokanee during its boom-and-bust cycles.

Russello and his team also looked at the DNA of kokanee being raised at the Whitehorse Rapids Fish Hatchery, the descendents of fish collected from the Kathleen Lake system in the '90s, and found they were no longer genetically similar to the kokanee in the lake today.

Russello said that means "it would not be optimal" to use the hatchery fish to supplement the wild kokanee population in the case of another crash; the hatchery fish have adapted a little too well to their artificial environment.

Introducing fish that are not as fit for the wild and breeding them with wild fish can "lower the fitness of the entire wild population."

Wong said there had been no imminent plans to release the hatchery fish into the wild.

"It was a back-pocket thing and there's lots of things that would have to happen to do that — you know, the whole concern about disease and all sorts of things," she said.

Their first step was to determine how genetically health the population was. Now, they've learned that it "wasn't a good fit" and that reintroducing hatchery fish may not be the "right tool" for conservation.