Documentary reveals how two Charlotte men discovered an ugly past and confronted it

When the final credits faded, and a once-darkened theater inside a near-capacity Independent Picture House in NoDa slowly regained light, Jimmie Lee Kirkpatrick and De Kirkpatrick were adorned with applause and overwhelming praise.

A two-hour feature documentary entitled “A Binding Truth” explored the emotional journey of men at opposite ends of the racial spectrum immersed in a yearslong search for ancestral truths that connected them and gnawed at their spirits gripped the audience.

The Kirkpatricks — Jimmie Lee, a Black man; De, white — grew up in Charlotte, sharing a last name and graduating from Myers Park High School together a half-century ago. De was from a blue-collar family in a middle-class neighborhood in Dilworth; Jimmie Lee lived in the Black neighborhood of Grier Town, now known as Grier Heights.

While the film, which premiered last week in Charlotte during private screenings, was inspired by a series of articles by former Charlotte Observer reporters Gary Schwab and David Scott about the Kirkpatrick’s ties through slavery, the tale ultimately is an examination of America’s struggles to reconcile a history shaped by racism and how people can move forward despite of it.

“This is a healing story,” Jimmie Lee said of the film documenting his journey. “It has released me from these inhibitions that I had around these subjects. It’s given me the motivation to continue.”

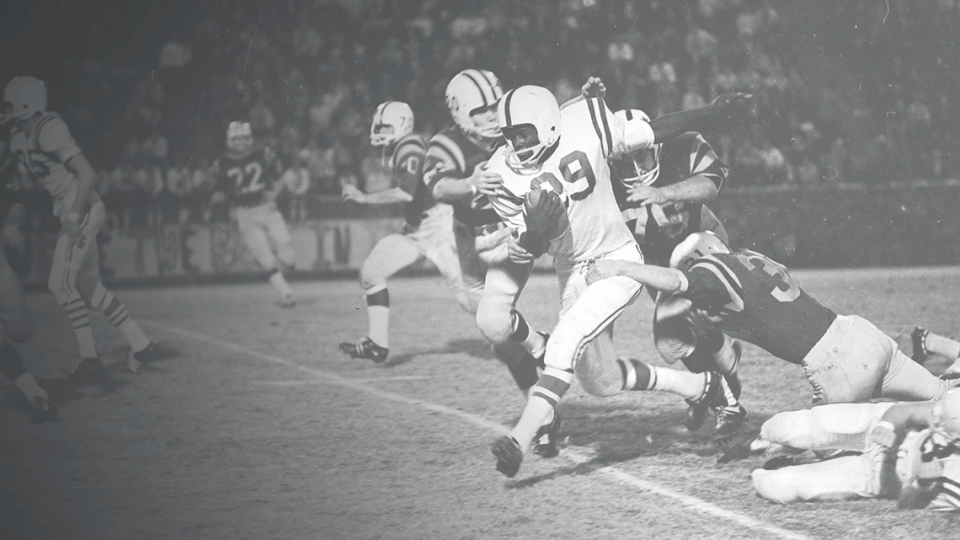

Much of the documentary centers around Jimmie Lee, a star football player at all-Black Second Ward High School who transferred to predominately white Myers Park in 1965, and what that meant through the lens of race.

He gained prominence back then for being the focus of a Civil Rights lawsuit after he was not allowed to play in the Shrine Bowl All-Star game because he was Black. However, that omission and the lawsuit filed by Charlotte activist Julius Chambers led to the desegregation of the game.

The homes of the four Civil Rights leaders involved in the case — NAACP president Kelly Alexander Sr., city-council member Fred Alexander, Dr. Reginald Hawkins, and Chambers — were firebombed in response to a judge’s decision.

A phone call changed everything

The film then transitions to Jimmie Lee, later heading to Purdue University on a football scholarship but dropping out in 1969 after suffering a career-ending knee injury and joining the anti-war movement in California. He moved to Oregon to perform odd jobs and made new friendships playing a band.

The Myers Park classmates had lost touch over the years until a 2013 Observer series about Jimmie Lee’s story sparked De to regain connection.

During a two-hour phone conversation, Jimmie Lee asked about the “H” in his initials “H.D.” It stood for “Hugh,” De told him, to which Jimmie Lee shared how De’s great-great-grandfather, also Hugh Kirkpatrick, had owned his great-great-grandfather, an enslaved person named Sam.

The men learned that more than 30% of Mecklenburg County’s population in the 1860s were slaves. De, a forensic psychologist, discovered his great-great-grandfather owned 51 enslaved people, and his family had at least seven plantations throughout 1,400 acres of land within the county.

In one of the film’s first poignant scenes — shot over four years by director Louise Woehrie — Jimmie Lee visits Sardis Presbyterian Church Cemetery in Charlotte and walks among unmarked graves.

Taking it all in, Jimmie Lee says, “I feel protected here,” sensing that his ancestors were watching over him.

A cohesive American story

De lived in a home with a father who often told offensive jokes and used racist slurs. He wanted to investigate why “slavery was morally acceptable” in America. As part of his attempt to gain a deeper understanding, De spends one night in slave quarters on property run by South Carolina-based The Slave Dwelling Project.

De, who wanted audiences to grasp “how significant slavery was in Mecklenburg County,” was admittedly restless thinking about the horrors enslaved Black people endured during his temporary stay.

“It is possible to tell a cohesive story about something as complex as the American history of slavery and its implications that make sense,” he said of that film that he was “pleased” and “satisfied” with.

The film weaves in perspectives from former Charlotte Mayor Harvey Gantt, Charlotte historian Willie J. Griffin and Emma Peoples Smith, a 95-year-old white woman who revealed her connection to the Black Kirkpatrick family that added another layer to the twisting narrative that can only be understood by viewing the film.

The audience even learns that Jimmie Lee is the distant brother of heavyweight champion boxer Mike Tyson.

Learning history through the Kirkpatricks

Augmented reality shows the juxtaposition of present-day Charlotte with its past. In one scene, Jimmie Lee and his son, J.J. Kirkpatrick, walk around uptown and stop at Bank of America Stadium. The home of the Carolina Panthers was where Good Samaritan Hospital, a Black hospital, once stood and where Jimmie Lee was born.

Charlotte, much like Jimmie Lee’s story, had evolved.

“This story first started as a sports story about football and then a civil rights story,” said Jimmie Lee. “Then some of my discoveries led to De’s and I connection. A lot of people can relate to it, and it touches people.”

From the backstory of Jimmie Lee and De Kirkpatrick to how the relationship of race defined Charlotte, Woehrie explained that the film is a conversation starter to confront those divisive issues head-on.

“Their story could set the table for conversation for telling the truth,” she said, “and for people to be open to the truth about the history of slavery. Because their story is so personal, it engages us in a way that we are learning about the history through their experiences.”

Future screenings for “A Binding Truth” are pending, though updates about the film’s public availability can be found at www.whirlygigproductions.com.