Elliot Lake fatal mall collapse comes down to 'human failure,' report says

The head of the public inquiry into the fatal 2012 Algo Centre Mall roof collapse in Elliot Lake, Ont., more than two years ago, says the real story behind the tragedy was “human failure."

In his final report, revealed to members of the community Wednesday, Justice Paul Belanger said "many of those whose calling or occupation touched the mall displayed failings — its designers and builders, its owners, some architects and engineers, as well as the municipal and provincial officials charged with the duty of protecting the public."

Lucie Aylwin, 37, and DolorisPerizzolo, 74, died and 19 others were hurt in the collapse.

“Apathy, neglect and indifference to mediocrity, ineptitude, incompetence and outright greed” riddled the fate of the mall, the report says.

Some engineering inspections were so cursory and incomplete, they were essentially meaningless, he continued.

"Secrecy and confidentiality often trumped candour, transparency, and openness.

"Based on any fair and objective analysis of the history of the Algo Mall as it unfolded during the commission's hearings, it is difficult to resist the conclusion that, if any one of the owners, engineers or officials who were involved with the mall over its 33 years of existence had insisted: ‘enough … this building will fail if it isn't fixed,’ two lives would not have been senselessly and tragically lost."

The report was released at a local community centre — two years and four months after part of the mall's rooftop garage caved in following years of water and salt penetration.

Some key recommendations include:

- The province should establish minimum standards of maintenance for buildings like the Algo Centre Mall.

- Properly qualified structural engineers should inspect buildings when sold, more frequently if public safety dictates.

- Make information about building condition easily accessible and understandable to owners, the public and potential buyers.

- Enforcement of standards should be straightforward and make public authorities accountable for their decisions and actions.

- Professional engineers and municipal building officials should be trained and certified, and information about them accessible to owners and the public.

- Increase capacity of search and rescue teams to respond to structural collapses.

- Have one person in charge of an emergency response.

- Improve communications among emergency responders, and between responders and the public, especially victims.

- Improve federal funding of heavy search and rescue teams across Canada.

Belanger has released two volumes of the report, along with his recommendations. Below is his executive summary:

Aylwin 'might have been rescued'

While Perizzolo's death was "mercifully quick," Aylwin might have lived for as long as 39 hours, Belanger concludes. He notes "tantalizing" signs she was alive for some time: responsive tapping, a muffled voice, indications from search dogs.

"There exists a possibility she might have been rescued," he writes. "But we will never know for sure."

What is clear is that the disaster began unfolding in the 1970s. The mall, Belanger concludes, was "doomed to early failure" while still in its planning stages.

Putting parking on the roof was a bad idea. The defective roof design — using an untested combination of materials — made matters much worse.

"The system was a dismal failure from the moment it was installed," the report states.

Ironically, the mall seldom lacked for professional oversight from architects and engineers, with some 30 visits, inspections and reports over its 33-year life.

However, the scrutiny never translated into a proper fix for the leaks that prompted some to dub the centre the "Algo Falls." No one, it seems, appeared to realize how severely the rust would compromise the integrity of the structural steel.

Engineer's work 'markedly inferior'

Some of the engineers involved simply forgot the "moral and ethical foundation" of their vocation and, Belanger concludes, were more concerned with pandering to clients than with protecting the public.

The commissioner was particularly critical of Robert (Bob) Wood, the engineer who signed off on the health of the mall just weeks before it collapsed. His work and conduct, Belanger says, were "markedly inferior."

Wood, who faces criminal charges in connection with the collapse, admitted to falsifying his report to appease the owner.

"His review was similar to that of a mechanic inspecting a car with a cracked engine block who pronounces the vehicle sound because of its good paint job," the report states.

According to the commission, the mall's various owners hid the problems, then tried to sell their way out of them when patchwork fixes didn't work. Profit considerations trumped all other concerns, Belanger says.

The "crafty" and intransigent Bob Nazarian, who owned the mall when the disaster struck, lied about repair work, and resorted to "subterfuge and falsehood to mislead authorities, tenants and the public," the report concludes.

Wilfully blind municipal officials — the mayor, council and building inspectors — were of little use in dealing with the worsening problems.

They ignored public complaints and warnings about the leaks and falling concrete. They illegally shut the public out of meetings. They failed to enforce, or were ignorant of, their own bylaws, according to the report.

Instead, their approach was one of "non-interference" aimed at safeguarding the mall as a social and economic hub that provided significant tax revenues.

'Warning signs went unseen'

At one point, Belanger notes, the municipality was the mall's owner, its tenant, and enforcer of property standards — the "worst possible conflict situation."

"Warning signs went unseen by eyes likely averted for fear of jeopardizing the mall's existence," Belanger says.

"Occasional voices of alarm and warning blew by deaf and callous ears."

The report also notes that officials with the provincial Ministry of Labour, which had offices in the mall, appeared curiously indifferent to the state of disrepair, and unresponsive to complaints.

In all, the report makes 71 recommendations. They include setting minimum maintenance standards for buildings, beefed-up inspections, and an expanded emergency response capability.

Belanger is effusive in his praise for the initial local emergency response. His view of the provincial heavy urban search and rescue team that was called in — despite the good intentions and courage of its members — is far more jaundiced.

The team deployed without sufficient numbers, without a proper plan or command structure, and treated family members and the community poorly, he says.

They also ignored an offer of help from experienced mine rescuers. They called off the search due to the dangerous conditions instead of simply putting the effort on hold while they considered other options.

"Ontario's urban search and rescue system needs a careful re-examination to provide better overall coverage and quality of service," Belanger concludes.

The rescue effort, he says, was not a model that others should strive to emulate.

He does, however, praise then-premier Dalton McGuinty for getting the rescue effort restarted.

Inquiry report offers 'closure'

The public inquiry into the mall disaster held months of hearings and examined thousands of documents.

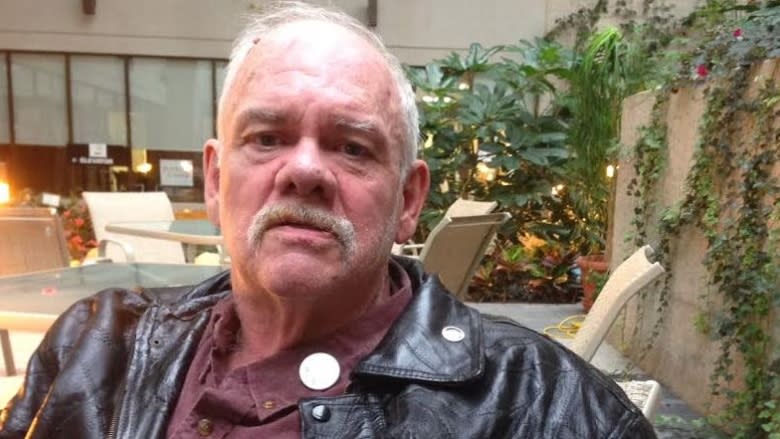

Keith Moyer, a member of an Elliot Lake advocacy group for seniors, followed the inquiry hearings almost daily.

"I have expectations that he [Belanger] is going to come out with some very worthwhile doable recommendations, and just hope that those with the power to implement them do so," he said before the report was released.

Luc Morrisette, who owned a flower shop in the mall before its collapse, said he remembers what rainy days were like inside his store.

"You're dodging the leaks all over the store. There would be new buckets all over. But it was a daily thing, so you almost get used to seeing those buckets," he said.

Despite his misgivings, Morrisette kept his store in the mall for 16 years — until the day the rusty ceiling beams gave in to decades of water and salt that had leaked through from the roof-top parking deck, sending cars and concrete down into the mall.

Morrisette said he planned to be in the front row Wednesday when Belanger released his report.

"It's closure. I need to see this first-hand."

The final report is not aimed at laying blame. Instead, Belanger's recommendations aim to prevent similar tragedies.

Morrisette said he hopes the release of the report will allow the community to finally move on.

"Elliot Lake is a nice tranquil place. The people who know us, know how beautiful this place is."

Lawsuit ahead

Police, who have charged a former engineer criminally, are still investigating the collapse.

In February, a judge approved a class action lawsuit brought by those who suffered losses in the Algo Centre Mall collapse. About 300 people and businesses are seeking damages. There are 13 defendants, including the province of Ontario, the City of Elliot Lake, and the former and current mall owners.

The judge's decision also rejected the province of Ontario's argument that it should not be a defendant, and said Ministry of Labour inspectors should be held to account.

The lawsuit was launched by Elaine and Jack Quinte, who lost their restaurant in the mall during the roof collapse.