Ex-General Becomes Cat-Loving Grandpa in Bid to Run Indonesia

(Bloomberg) -- The odds have never looked better for Prabowo Subianto to win Indonesia’s highest office.

Most Read from Bloomberg

Xi to Discuss China Stocks With Regulators as Rescue Bets Build

Wall Street Snubs China for India in a Historic Markets Shift

A former military general, Prabowo was dismissed for alleged human rights abuses, exiled in Jordan, then banned from the US for two decades. He’s temperamental, volatile and known for pounding tables and fiery nationalist speeches. The former son-in-law of Indonesia’s late dictator Suharto, he twice lost the race to become president to Joko Widodo, popularly known as Jokowi. The last time, in 2019, he fought a bitter months-long campaign to overturn the results before eventually joining Jokowi’s cabinet as defense minister.

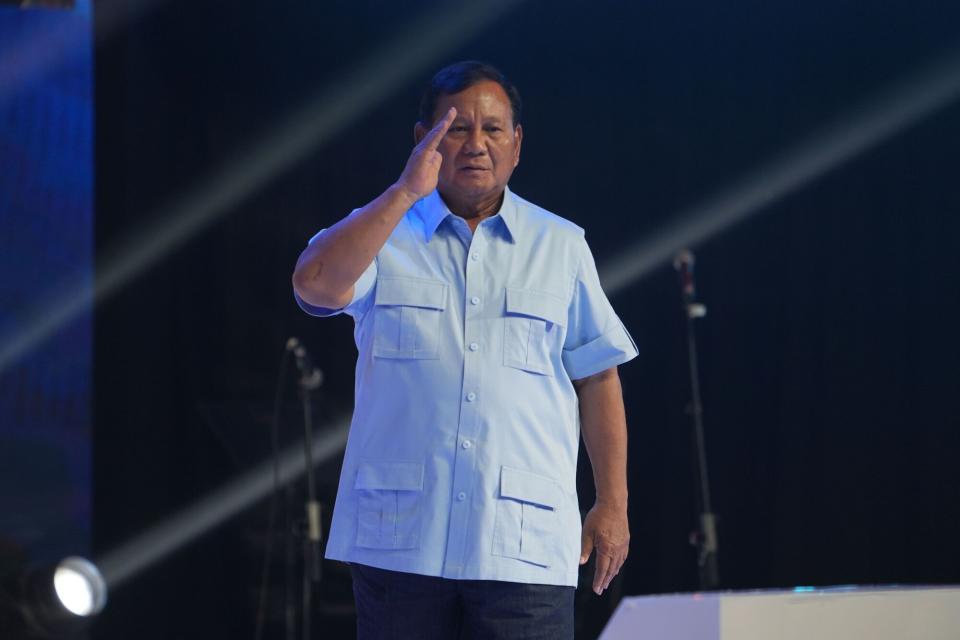

Today, as he stands on the cusp of potentially claiming an outright win in elections scheduled on Feb. 14, Prabowo is reaping the rewards of an extensive image makeover. Over the past few months, helped by a social media campaign that features his cats, dance videos and cartoonized portraits, the 72-year-old has tried to come off as a cuddly grandpa.

He’s also more affable in public appearances. And most significantly, he’s successfully ridden the coat tails of the very man who beat him the last two times: the country’s most popular politician, Jokowi, whose 36-year-old son Prabowo picked as his running mate.

The success of that makeover is evident among young voters - and more than half of the country’s 200 million voters are under 40.

Take Rika Karmila, a 30-year-old content creator who was among the thousands of supporters who attended a rally in the capital Jakarta last month. Like others at the event, she was dressed in light blue, the campaign’s official color, danced to their hip-hop theme song, waved the Indonesian flag and cheered loudly when Prabowo did his iconic ‘adorable dance’ on stage.

To Rika, voting for Prabowo is obvious: he is a “sincere” leader on his third bid for presidency and an ally of younger citizens. Asked, she brushes aside the allegations of Prabowo’s dark past.

“Those are attacks on Prabowo. He was following orders and if he was actually wrong, he wouldn’t be in the government,” she said at the rally, referring to his alleged role in kidnapping student activists during the anti-government protests in 1998. Later, supporters erected a 4-meter-tall cartoon portrait of the ex-general cuddling a cat.

Jokowi picked Prabowo as his defense minister as an act of reconciliation, after the campaign’s bitterness that led to deadly clashes in Jakarta. Today, many analysts see the president’s implicit support for Prabowo as Jokowi’s way of continuing to influence politics — and cement his legacy — after he steps down later this year.

To Rika, voting for Prabowo is also the surest bet to continuing Jokowi’s economic policies so that Indonesia could one day “become equal to a country like America.”

The country has grown at an annual average of 5% over the past decade — except during the pandemic — as the president poured money into infrastructure and attempted to move the archipelago up the global metal supply chain. Jokowi’s goal is to make Indonesia a developed country by 2045.

“We are not ashamed to say: we are team Jokowi,” said Prabowo in his speech at the rally, “We’ve been selling our natural wealth to foreign nations for minimal prices. That doesn’t make sense. We have to process all our natural wealth on Indonesian soil.”

Prabowo’s pledges aside, given his past volatility, temper and single-minded pursuit of the top job, analysts say there is no guarantee that he will faithfully execute Jokowi’s vision, or be as pliable as the Indonesian president might like him to be.

“He is a fundamentally different kind of leader to Jokowi: more volatile, more aggressive, and obsessed with projections of strength,” said Ian Wilson, Senior Research Fellow at the Indo-Pacific Research Centre of Murdoch University. “So shifts in approach and policy are almost guaranteed.”

Temperamental Man

As Jokowi’s defense minister, Prabowo has largely kept a low profile — with no notable successes to boast about. Tasked with modernizing the country’s bloated and creaking military, he has focused on the acquisition of big-ticket weapons platforms from a variety of countries. His critics have questioned the purchases for interoperability issues. Broadly, they say the challenges faced by Indonesia’s military remain unchanged under Prabowo.

Read: Indonesia Struggles to Build Military That Can Stave Off China

His most viral moment however made most observers cringe - and provided a window into Prabowo’s style.

At an international defense forum in Singapore last year, Prabowo, seemingly on the fly, proposed a peace plan to end the conflict between Russia and Ukraine — one that favored Russia. The proposal was ridiculed by most Western observers, left the Ukrainians fuming and did not reflect Indonesia’s official stance. Worse, Jokowi had no prior knowledge that his defense minister would float such a proposal in a public setting.

“What we’ve seen with him [Prabowo] is that policy announcements tend to be less developed before they were announced,” said Evan Laksmana, senior fellow for Southeast Asia military modernization at the International Institute for Strategic Studies. “Which means it’s very dependent on that particular mood and moment, and a mood and moment type of foreign policy is a tricky one because you don’t know what you’re gonna get.”

A Gamble

Prabowo has been leading the polls against former governors Ganjar Pranowo and Anies Baswedan for this year’s election (46% versus 23% and 26% respectively), according to a recent survey. He’s said he would “go to a mountain and retire” if he lost again.

Prabowo established that lead, in part, by securing Jokowi’s support. Doing so has meant potentially netting as many as 37 million additional votes through a coattail effect, a number that has been rising the past half year as the president has gained in popularity, according to a survey. He’s also copied aspects of Jokowi’s style, including of making impromptu visits.

“The 2024 presidential election is Prabowo’s last and best opportunity due to his age and Jokowi’s support,” said D. Nicky Fahrizal, a researcher at the Jakarta-based Centre for Strategic and International Studies. “What he is doing now is copying President Jokowi’s gimmick and continuing what Jokowi has been doing for the past 10 years.”

Jokowi’s gamble is, on paper, just as obvious: with Prabowo agreeing to his own son as the vice president, Jokowi has “a channel to be involved in policymaking,” said Erry Riyana Hardjapamekas, a pro-democracy activist.

Other analysts however are not so sure. Prabowo was a leading critic of Jokowi during his first term — and dismissive of his infrastructure push, saying many projects were “rushed” and more “monuments” than actual public goods.

“One thing we don’t know is whether Prabowo has his own mind,” said Alexander Arifianto, a senior fellow with the Indonesia program at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies. “Whether he sees his alliance with Jokowi to be a long lasting one, or just something he has to do to win the election and then after that he can move Jokowi and his son aside.”

Prabowo has espoused ideas beyond merely continuing Jokowi’s policies. He’s pledged a 400 trillion rupiah ($25.5 billion) free school lunch and milk program as his flagship economic policy. It’s an expansion of his 2019 campaign promise to provide free milk for school children.

The program is expected to help boost economic growth to 6%-7% by helping local farmers and freeing up more income, according to Drajad Wibowo, an economist affiliated with Prabowo’s campaign. The campaign has also said that it won’t fuel inflation or raise debt.

Appealing to rural, small town voters, in addition to the younger voters, has been key to Prabowo’s success so far.

“If he keeps his tone in the campaign, then it’s very unlikely of him not to win,” said Achmad Sukarsono, an associate director at Control Risks, with a focus on Indonesia. “It’s Prabowo’s election to lose.”

--With assistance from Philip J. Heijmans and Faris Mokhtar.

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.