Execution anniversary of Louis Riel inspires exhibit of rare, curious items

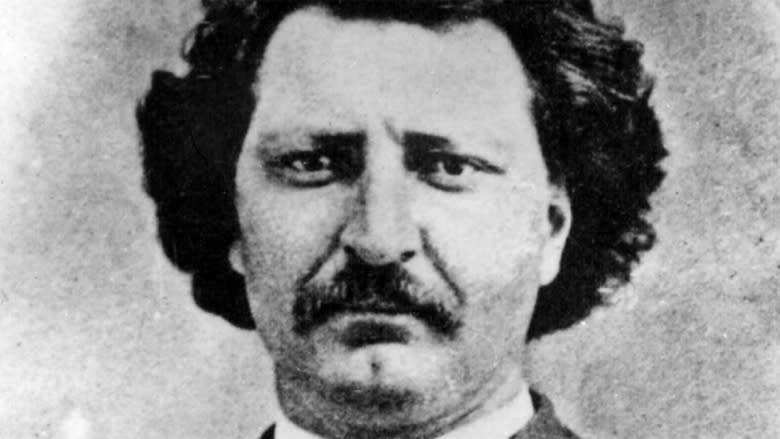

It's been 132 years since Louis Riel was hanged for treason, but interest in the leader of the Métis and the founder of Manitoba has never waned.

That's evident in the number of media stories that continue to be published, the ongoing debate about whether he was a traitor or a hero, and other materials — music, magazines, paintings, postcards and poems — produced about him.

A collection of those, including many rare items, will be showcased Thursday at Bison Books on Graham Avenue in downtown Winnipeg. Everything in the show, which runs from 1 p.m. until 5:30 p.m., is for sale.

"One of the things I really like about the collection is how varied it is, the fact that it goes from the period when Riel was still alive right up to contemporary time," said Bison owner Aimee Peake.

"The thing that really speaks to me is how the depth and width of materials relating to Riel really speaks to his cultural currency and how important he is and how important his legacy is to Manitoba."

The collection includes a first edition copy of a booklet of poems written by Riel and published by his family in 1886, shortly after his execution.

The catalogue for the show notes the last page in the booklet contains a printed certificate stating: "We, members of the Riel family, declare and certify that this is a true copy of the documents written and composed by Louis 'David' Riel."

On the more contemporary end is a record from a garage punk band from the 1990s, as well as the Chester Brown graphic novels about Riel.

"And there's a magazine that was published by the RCMP 50 years after the hanging of Riel, wherein a bunch of the Mounties reminisce about their experiences during the rebellion," Peake said.

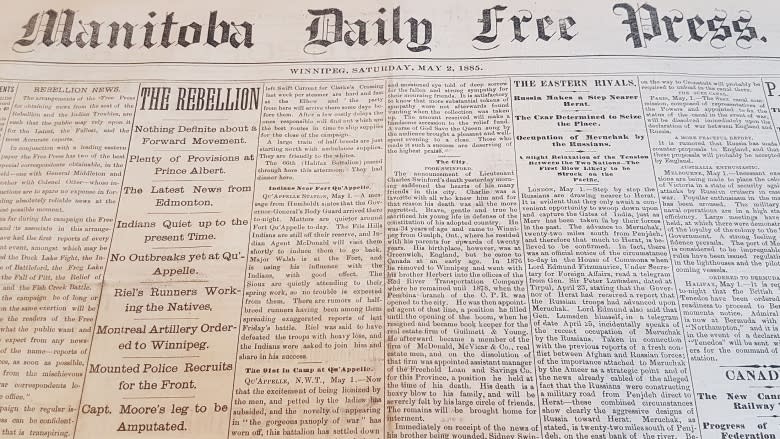

One of her favourite items is the collection of newspapers from 1885. One set of volumes contains the entire year's original copies of the Manitoba Daily Free Press with the exception of Nov. 24. Another contains the Winnipeg Daily Times from Jan. 4 to July 30.

Peake has set them on display, side-by-side, for people to compare coverage of events relating to Riel, which differ depending on the political slant of the newspaper's ownership.

"It's quite fascinating to look from one to the next and see the difference in editorial opinion. Also, to follow the events of the year as they happened from day-to-day — it puts it in a larger context because you get to see what else was happening at the time," she said.

"You're not just reading a book specifically about one of the rebellions, you're reading about all the other things that are happening in Manitoba and around the world. They paint quite a vivid picture of what was happening in 1885."

That contrast in perspective on Riel is also represented in books written about his provisional government and the terms he negotiated for Manitoba to enter Confederation. Those more sympathetic call it the Red River Resistance, while others see it as the Red River Rebellion.

Riel, born in St. Boniface, Man., sought to preserve Métis rights and culture as their homelands were encroached on by settlers.

The Red River rebellion/resistance followed the Canadian government's purchase of Rupert's Land, a vast northern and western swath of what is now Canada, from the Hudson's Bay Co.

Riel led the establishment of a provisional government in the Red River settlement (now the Winnipeg area) to protect the property, religious and language rights of people who already lived in the region.

The flashpoint was the execution of Thomas Scott, an Ontario-born member of an anti-Riel faction, in March 1870, after he was found guilty of treason against the provisional government.

The execution prompted Ottawa to send a military expedition to enforce federal authority in Red River.

Riel fled to the United States before the Canadian troops arrived, but when Manitoba entered Confederation in 1870, the act incorporated some of the terms his government originally laid out.

Riel's exile ended in 1884 when Métis in Saskatchewan called on him to help protect their rights. That resistance turned into a military operation once again as Canadian troops arrived in the area and culminated in the Battle of Batoche.

Riel was captured and faced a trial in Regina. On Nov. 16, 1885, at the age of 41, he was hanged for high treason.

A Thomas Scott medallion is one of the items in the Riel exhibit at Bison Books. It dates to 1900, when the local Orange Order in Winnipeg made plans to build a memorial hall named after Scott.

The special medallion is stamped with the words: "T. Scott. Murdered at Fort Garry, March 4, 1870."

Searches have not been able to find a similar medallion in any archival institution, nor has one recently been offered for sale, the catalogue for the exhibit says.

Tribute to 2 men

Peake said the exhibit is also a tribute to another man — Michael Park, whom she calls her mentor.

Park, who died in May at age 71, owned and operated Greenfield Books on Academy Road. He was a longtime antiquarian bookseller and president of the Antiquarian Booksellers Association of Canada.

Peake worked for him and later bought Bison Books, another store Park owned, from him.

Park had been collecting "interesting and unique" Riel-related materials for about a decade before his death with the intention of eventually putting together a catalogue.

After Park's death, Peake stepped in to help operate Greenfield Books. It was then that she and the staff decided to fulfill Park's vision in Canada's 150th year.

"We decided we would issue a catalogue in his memory and to celebrate the collection he put together," she said.

There are close 110 items in the catalogue but Peake has added a few items since it was printed, things she has picked up here and there. One is a limited edition lithograph of a painting of Riel's fire-damaged coffin by artist Kurt Wiscombe.

A description accompanying the image says Riel's body was put into this coffin and originally slated to be buried in the gallows enclosure in Regina, but an order from the lieutenant-governor of the time changed that plan.

Riel's body was sent to his mother's home in St. Vital and placed in a more elaborate coffin that was later buried in the churchyard of the St. Boniface Cathedral.

The original coffin was kept by his family and for years held his personal belongings, and papers. Some years later, the family donated it to the St. Boniface cathedral, where it remained until a fire destroyed the cathedral. The coffin was damaged, losing most of its lower half, and today it resides in the St. Boniface Museum.