New exhibit in Prince George gallery brings personal perspective to Métis history

Growing up in the northern B.C. community of Fort St. James, Erin Stagg was surrounded by Carrier culture and learned all about it. At the same time, she found out very little about her own heritage.

As a person of Métis descent, she says her lack of knowledge about the Métis people struck home when she was about to become a mother.

"As I got pregnant, I realized, 'What am I going to tell my daughter?' And so I kind of dug in, and I learned," she said on CBC's Daybreak North.

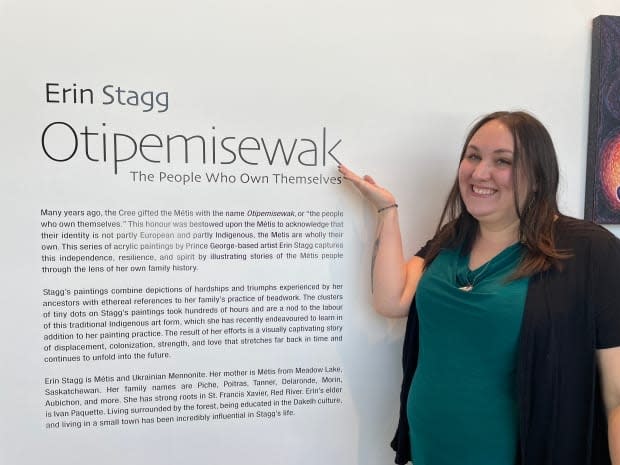

Stagg is now an interdisciplinary artist who lives in Prince George, about 160 kilometres southeast of her hometown. Last week, she was front and centre in the opening of her new exhibit at Prince George's Two Rivers Gallery.

The exhibit springs from Stagg's learning journey. It's called Otipemisewak: The People Who Own Themselves, and it illustrates — through a series of acrylic paintings — stories of the Métis people through Stagg's own family history.

"I found many of these stories through different parts of my life and I've brought them all [together in this exhibit] to help me tell stories to my people — to my family, to my brother, to my daughter, to my mom — and to other people so that it can be a way of educating about Métis history in a way that's really beautiful," she said.

One of the paintings in the exhibit, Buffalo People, features Stagg's second great-grandfather, Zachary Piche, standing on a hillside in front of a stationary buffalo, with a Métis settlement down below. Stagg says her inspiration came from a photograph of Piche she stumbled across in a museum in Willow Bunch, Sask.

Stagg says seeing Piche come to life in a painting is more meaningful than just seeing his name in her family tree.

Métis history tied to fur trade, North-West Rebellion

The Métis Nation of Alberta website describes Métis people as a post-contact Indigenous nation, born from the unions of European fur traders and First Nations women in the 18th century.

The Métis homelands include Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, parts of British Columbia and Ontario, the Northwest Territories, and the northern United States.

Métis history is tied to the fur trade, the buffalo hunt, the North-West Rebellion and the Métis scrip, a certificate that could be traded for land or money.

The Métis Nation of Alberta website says the scrip system was "rife with fraud and abuse" as most scrip certificates ended up in the hands of land speculators who resold them for profit — often fraudulently — "and left the Métis with next to nothing, including our rights and claims to the land."

Artist communicates 'really beautifully' through her work

Kait Herlehy, acting curator at Two Rivers Gallery, says Stagg's Otipemisewak exhibit shares stories of the Métis in an accessible way.

"Communicating through art is a really wonderful way to reach new people and I think she does it really beautifully," Herlehy said.

"I've had a lot of people in the brief time it's been up so far tell me this is the first thing that they've seen in a while that has really made them feel something, which is exactly what you want to hear."

Herlehy says Stagg's work is made powerful through its representation of family history in the larger context of the Métis people.

"I think what we're taught in school about the history of the Métis people, and about colonization in Canada at large, is so one-sided and so sterile," she said.

"And I think Erin gives people the opportunity to learn that history in a much more personal and thoughtful and poetic way."