Facing Inuit teacher shortages, Nunavut Education Minister wants to move deadlines on bilingual instruction

Nunavut's celebrated 2008 Education Act promised to deliver fully bilingual education to students by 2019.

But that's not going to happen.

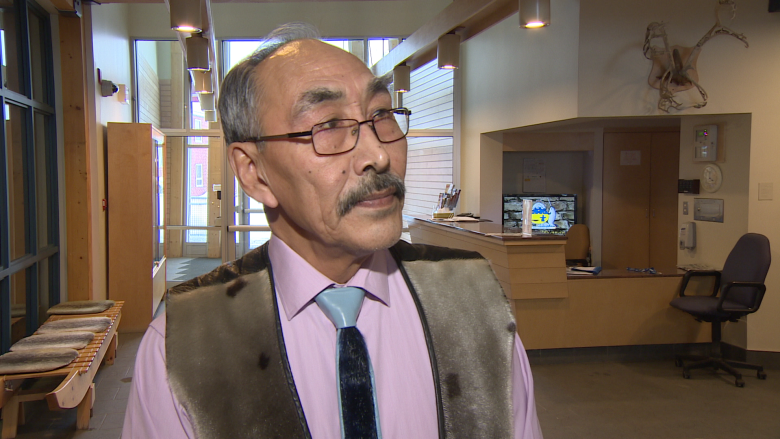

"Due to the fact that we have been short of Inuktitut teachers and [a] lack of resources, this is something that we have not been able to meet," Education Minister Paul Quassa told reporters shortly after introducing a bill to update the act in the legislature last week.

The proposed changes would push the deadline for offering bilingual education to 2029 for Grades 4 to 9, and postpone the deadline for Grades 10 to 12 indefinitely.

The same act proposes changing the 2008 Inuit Language Protection Act from giving every child the right "receive Inuit language instruction" to giving every parent "the right to receive the majority of the child's school instruction in the Inuit language."

In a technical briefing with media Friday, deputy minister Kathy Okpik admitted that the original act was "aspirational" and "emotional," and said it "grossly underestimated" the challenges of offering Inuit-language education.

"Many lessons have been learned since 2008 about how our education system functions," she said.

The role of DEAs

The proposed changes follow an extensive review of the act in 2015, and a series of public consultations.

That review had called for a significant reduction in responsibilities for district education authorities.

The new bill proposes fewer changes:

- DEAs could still choose the school calendar, but would be limited to a range of options set by the minister;

- DEAs would have first choice to offer early childhood education programming, but the minister could step in to offer this if the DEA chooses not to;

- DEAs would have a choice of how they want to offer bilingual education, but that choice would be limited by the capacity of Inuit-language-speaking teachers available.

The department wants to offer different language of instruction models that make the most of limited resources. That could include a "team teaching" model, where students spend half the day with an Inuit-language-speaking teacher and half with an English speaker.

The bill also lays out the duties of the Council of District Education Authorities, a new, elected body designed to replace the Coalition of District Education Authorities, a registered society.

Education officials say the new council will have more accountability, as well as better benefits for staff, though the council will remain independent from government.

Taking away rights

In a news release issued shortly after the bill received second reading in the house, Nunavut Tunngavik President Aluki Kotierk said the changes "reduce the right to Inuktut [Inuit language] instruction."

"The proposed changes appear to offer district education authorities (DEAs) a choice of instituting Inuktut language of instruction in schools, but without significantly increasing Inuktut-speaking teachers, DEAs will not be able to offer this choice to students," she noted.

A Toronto professor agrees. Ian Martin of York University says the proposed changes represent a significant "watering down" of the original intention of the land claim.

Former Nunavut languages commissioner Sandra Inutiq says reducing the right to Inuit language is a step back.

"What was the point of Nunavut, if it was not to protect language, and not to protect Inuit cultural rights, if we're to go down the path of what's being proposed, the creation of the territory was pointless."

The bill, Quassa said, is "now in the hands of the standing committee" on legislation.

He said the committee will provide an opportunity for more public consultations before the bill goes to a vote in the legislature.