When faculty feel ‘threatened,’ how do they push back? NC lacks a method used in FL

When universities are thrust into partisan political issues and debates, the people who teach and work on those campuses feel the resulting tensions firsthand.

They often push back, too.

But exactly how those efforts play out varies from state to state, and even university to university, depending on a variety of factors, including faculty morale and interest, shared-governance structures and the degree to which organizers hold legal power or recourse against decisions that elected leaders and university officials make.

At North Carolina’s public universities, faculty and staff aren’t allowed to bargain through unions to defend and improve their pay and working conditions.

Does that make their organizing less effective than in other states, like Florida?

It depends on who you ask.

What does faculty organizing look like in NC and Florida?

Public-sector employees in North Carolina, including faculty and staff at the state’s public universities, are banned under state law from collectively bargaining with their employers. While faculty and graduate student worker unions exist in the state, chapters at public universities do not hold legal negotiating power.

Jay Smith, a UNC-Chapel Hill history professor who serves as the state president of the American Association of University Professors (AAUP), a national faculty group, said North Carolina’s lack of union rights is one reason — but not the only one — that the state’s AAUP chapters have historically not been as active as unions in other states, like Florida.

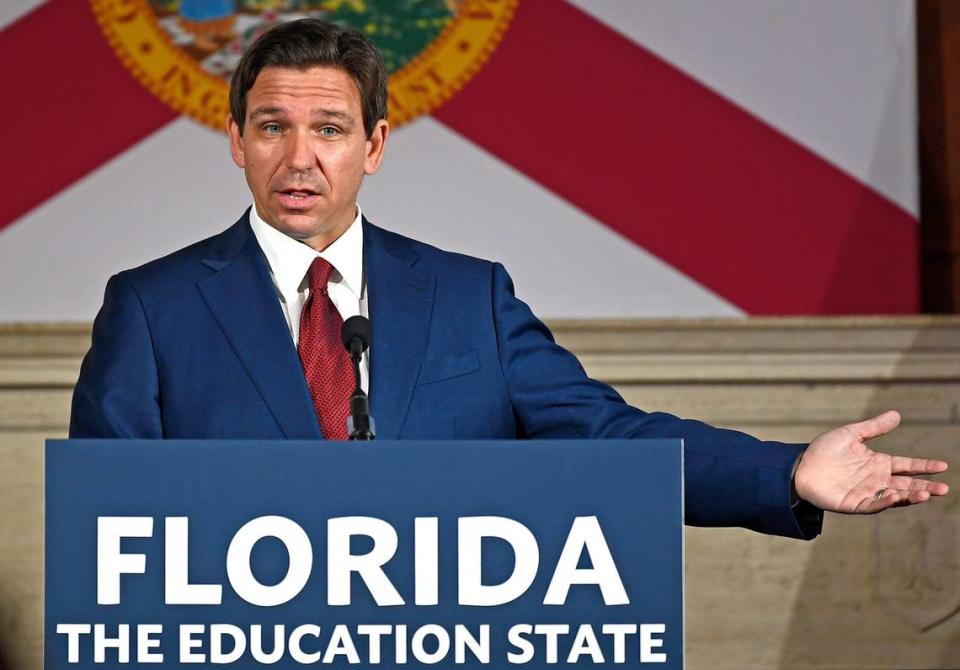

In that state, where Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis has become a symbol of controversial changes to higher education since 2018, public university faculty and graduate student workers have consistently pushed back against state legislation through protests and demonstrations — and, in some cases, filing lawsuits.

Those efforts are often organized through a large network of the state’s faculty and graduate student unions — 12 university faculty chapters and 17 college chapters under the United Faculty of Florida, plus Graduate Assistants United — which have “the right to self-organization” and collective bargaining under state law.

GAU-UF Co-President Bryn Taylor said being part of a bargaining unit provides members with legal protections that other organizations do not.

Faculty and graduate student unions serve a variety of purposes, including bargaining for better contracts, filing grievances, government advocacy and providing resources to members, she said. In recent years, the union’s government affairs has become increasingly more devoted to combating higher education bills, Taylor said.

UFF and GAU were some of the most active voices at Florida universities opposing the reopening of campuses during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. They also distributed guidance to professors on how to teach under the now-blocked Stop WOKE Act, which bars instruction on certain racial and gender-related topics.

The constant battling between unions and the governor’s administration wears on members, Taylor said, and it hasn’t gone unnoticed by those in other states.

Taylor said she’s had conversations with union members who work at universities outside of Florida who are “very scared and nervous” about the changes they see in the Sunshine State.

“They’re desperately trying to keep what’s happening here from happening in their own state,” Taylor said.

Using the power of faculty advocacy in NC

But pushing back against legislation looks slightly different in states like North Carolina.

Instead of labor unions, North Carolina faculty often rely on the power of advocacy through campus-level AAUP chapters or other non-bargaining unions, or through faculty governance forums at their respective campuses.

“In this state, we’re all just advocacy chapters. No AAUP chapter, obviously, has tried to bargain collectively, because we can’t,” Smith said. “So, sure, that is one one reason why faculty have not instinctively rushed to the AAUP to protect their interests, because it’s not a union with any real power.”

University organizers in both North Carolina and Florida said that speaking out against elected leaders’ and university administrators’ decisions can be tiring and overwhelming, which may limit participation by some faculty who feel they do not have the time or bandwidth to contribute to causes in addition to their work.

Still, faculty in North Carolina — particularly at UNC-Chapel Hill — haven’t sat idle. Through the university’s Faculty Council and AAUP, they have pushed back against several controversial decisions in recent years, from the initial denial of tenure to journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones in 2021 to efforts this year to establish a School of Civic Life and Leadership, among others.

Smith also led an effort involving more than 700 faculty this year to speak out against a bill that would have ended tenure across the state’s public universities for prospective faculty. The bill died after it failed to progress past legislative committees.

Aside from AAUP and graduate worker unions at UNC, faculty also play a significant role in university governance through the Faculty Council, through which faculty share their voice “on the academic matters that lie at the heart of the university’s mission,” UNC’s website says.

Beth Moracco, who became UNC faculty chair in July, said she feels that the university’s AAUP chapter and the Faculty Council “have slightly different roles” that are “very complementary.”

Morocco said shared-governance structures — in which faculty, university administrators and governing trustee boards serve distinctive roles — are “critical” in allowing faculty to share their voice about decisions at the university.

“We need to be really vigilant about maintaining and promoting that and pushing back when we feel that it’s threatened,” Morocco said.

Morocco said she thinks the Faculty Council, among other issues, has been successful in calling for more transparency and faculty input in the development of the School of Civic Life and Leadership. Faculty have criticized the university’s Board of Trustees for its actions surrounding the proposal of the school, saying it skirted traditional shared-governance structures, in which faculty propose curriculum and academic units.

Mimi Chapman, who preceded Moracco as faculty chair, said “it’s certainly tempting to wonder” whether North Carolina faculty might have more recourse with the power of a legally-recognized union. But she noted that North Carolina and Florida continue to experience very similar political battles over higher education, despite the power unions hold in Florida.

Future of public unions at risk in Florida

Unions in Florida may have become hubs for resisting the recent barrage of higher education legislation, but a 2023 bill could put their influence in a precarious position.

Senate Bill 256, which was approved by DeSantis on May 9, introduced restrictions that put the survival of many public sector employees’ unions at risk. Among those limitations: barring unions from deducting dues directly from a member’s payroll and introducing a new threshold for unions to meet in order to stay certified.

At least 60% of members in a bargaining unit must pay dues for the employee union to continue providing representation, according to the law that went into effect July 1. One of the largest teacher’s unions in the state, located in Miami-Dade County, barely had 50% of their members paying dues in 2022, NPR reported.

Now, time is running out before Florida’s faculty and graduate student unions face the threat of decertification.

With a deadline of February for public unions such as GAU-UF to reach a 60% threshold, it has caused some worry among organizers like Taylor. Despite experiencing a 3% growth over the past year in membership, the union still needs to ramp up its recruitment effort, she said.

Taylor has tried to stay positive in the face of the daunting task of avoiding decertification, a responsibility she called “exhausting.” One part of the bill — no longer sharing payroll information with the university — can be a newfound, attractive aspect of joining a union, she said, because administration won’t have direct access to who is in the union.

In a way, she said DeSantis and his higher education agenda have been some of the “best organizers” unions could ask for. People who would have never considered joining the union are now doing so because they’re “really mad,” Taylor said.

“If anything, people are angrier now than they’ve ever been and the need for collectivization has become a lot more apparent,” Taylor said. “Because who else is going to protect you?”

Smith, the North Carolina AAUP president, said statewide membership in the organization has seen a “modest expansion” over the past year or so. He hopes the organization can use recent political developments in higher education to build on that momentum.

“We’re hoping to use this crisis to expand our membership,” Smith said, “and to make ourselves more active and more vocal.”