Faux paw: 1970s zoo 'dingo' in Saskatoon was actually domestic dog crossbreed

An old photograph of a sandy-coloured dog in a cage in Saskatoon has raised the question of what makes a zoo animal the real deal, as two new dingoes bring the Canadian zoo into an Australian conversation about the taxonomic and conservation status of the dingo.

The picture from the early 1970s, which is believed to have been taken at the Saskatoon Forestry Farm Park and Zoo, shows the animal clearly labelled as a dingo.

But records dug out of an old box of paperwork at the zoo office appear to show the animal was a hybrid of a domestic Labrador dog, a coyote and a dingo.

Tim Sinclair-Smith, the Australian manager of the Saskatoon zoo, said he wants to set the record straight by making the public aware that the dog in the photo was not a purebred dingo.

"There's a lot of … I guess dark history in zoos you know in days gone by where things were done very differently," said Sinclair-Smith.

"Hybridization of animals … it is not acceptable, it is frowned upon in and nor do we allow it any accredited professional facilities."

The question of whether the dog in the picture was in fact a dingo surfaced after the arrival of two young "purebred" dingoes, Maple and Euci, from Australia in August.

Lesley Avant raised the existence of the early zoo "dingo" after hearing the Saskatoon zoo's claim Maple and Euci were the first dingoes at a Canadian zoo. She doesn't know who took the photo but remembers seeing the animal, as well as others she thought were dingoes, herself.

"I remember going out to the zoo a few times and I remember seeing the dingoes," said Avant, who said she was not aware of the paperwork indicating the animals were domestic hybrids until now.

The Saskatoon Forestry Farm Park and Zoo opened in 1972, when the city purchased a menagerie of animals from the Golden Gate Animal Farm. The city agreed to buy the animals when the farm closed down.

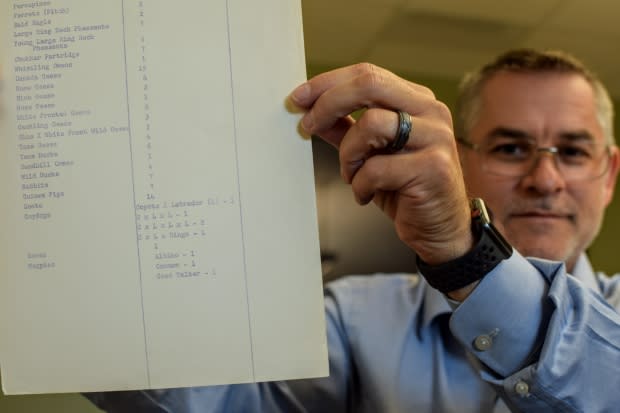

Before it closed, the Golden Gate farm kept an annual record of its animal inventory. From 1964 to 1965, a solitary dingo appeared on the list. But in 1966 it dropped off the list and seemingly reappeared as a subheading under another listing: Coydogs.

There were five "coydogs" listed in the inventory. All were coyotes (C) crossed with Labrador dogs (L) and the list was broken down to show the specifics of their breeding. One of the coydogs was listed as follows: C x L x Dingo. They were among the animals transferred to the city when the farm closed.

Sinclair-Smith believes this is proof that the animals previously referred to as "dingoes" at the zoo were not a dingo but a hybridized species mix.

He said it's a practice that used to be common in zoos.

"There's a lot of facilities out there that did that, you know, to come up with the next latest and greatest thing, because getting people through the gate and getting that revenue is extremely important," said Sinclair-Smith.

"So you know we've got to send that strong message out there that those ways of doing things in the past are not acceptable anymore."

Sinclair-Smith said hybridization "dilutes" the species, adding that there is no reason to do it except for financial gain.

He said breeding is particularly important in the case of the dingo, which is classified as a pest in some parts of Australia. It therefore does not receive the same protections as some other Australian species in those areas.

Sinclair-Smith said arguments against classifying the species as native or protected include beliefs that it has interbred so widely with domestic dogs that there are no "purebred" dingoes outside Australia's Fraser Island.

"With the advancement of DNA and us being able to more affordably test animals ... we can understand clearly what those populations are as we're out there testing," said Sinclair-Smith.

"The argument that they've been completely hybridized out there we're finding is absolutely not true, so that's one of the fights that we're pushing through.

"We need to protect them now to make sure that we maintain those populations and protect those areas … like we would for any endangered or threatened species."

Maybe Canada can learn from Australia's mistakes - Tim Sinclair-Smith, Saskatoon Forestry Farm Park and Zoo manager

A group of Australian scientists, including the director of the Australian Dingo Foundation, recently published an article in The Conversation arguing that the dingo is a native species having an "identity crisis."

The website for the Australian Dingo Foundation, which helped to bring the dingoes to Saskatoon, says the non-profit works with researchers on a genome project to determine the dingo's ancient origins.

According to Sinclair-Smith, the lack of government protection heightens the risk to dingoes because they are sometimes perceived as a pest to farmers. In Western Australia the law considers them pests that are allowed to be killed in areas where there is livestock, as long as the killing is carried out using legal methods.

"Western Australia's policy for wild dog management is to control all wild dogs, including dingoes, in and near livestock grazing areas in Western Australia," said a statement from the Western Australian Environment Minister Stephen Dawson in March, 2019.

"Currently, dingoes may be taken anywhere in the State without a Biodiversity Conservation Act licence, however, the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions will continue to manage occurrences of the dingo for their cultural and ecological significance on lands that it manages, such as in national parks and nature reserves."

The state of Queensland also protects dingoes in national parks but declares them pests outside of those areas.

"The earliest undisputed archaeological finding of the dingo in Australia has been dated to 3,500 years ago when it was likely introduced by Asian seafarers," says a fact sheet from the Queensland government.

"However, the Queensland Museum notes that recent DNA studies suggest dingoes may have been in Australia even longer (between 4,640 and 18,100 years)."

Sinclair-Smith believes pressure from the livestock industry is the reason the dingo remains unprotected in some areas.

He hopes bringing the dingoes to Saskatoon will help raise global awareness and increase public pressure on Australian state governments to introduce more protection for the dingoes.

"Maybe Canada can learn from Australia's mistakes, you know, and vice versa," said Sinclair-Smith.

"I think there's opportunities to always learn from each other. I think bringing things to an international stage can help put pressure on us because sometimes a different perspective from somewhere else can give you a new light on the situation."