Florida’s affordable housing board places DeSantis’ chosen director on leave again

Gov. Ron DeSantis’ affordable housing director was placed on administrative leave for a second time after an investigation determined he created a hostile work environment and violated other policies.

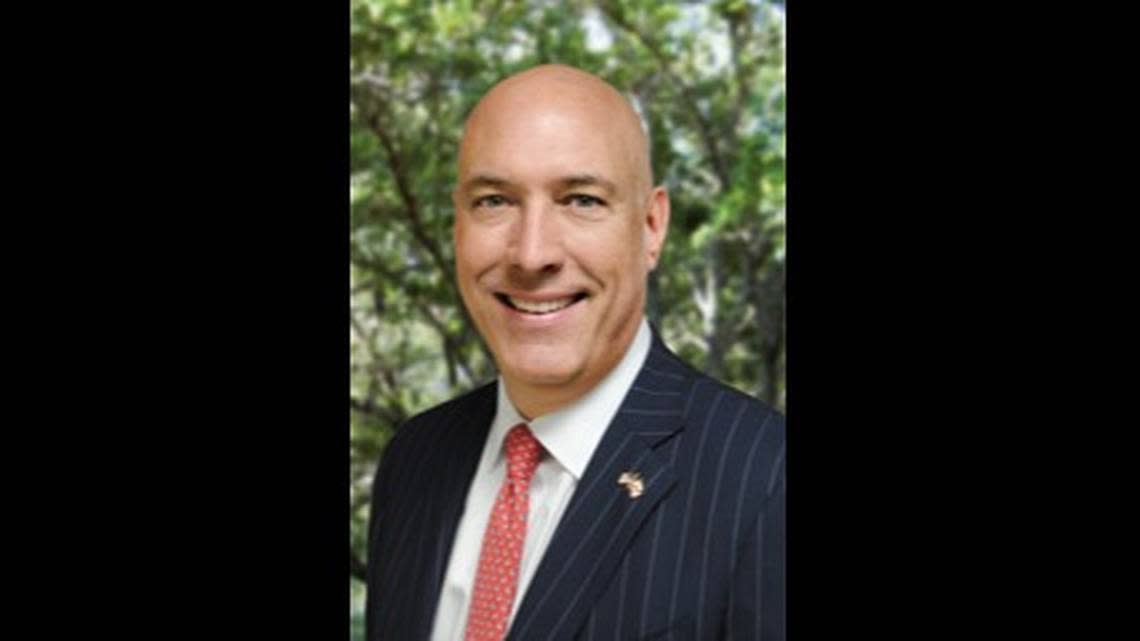

During a Friday meeting, the board of the Florida Housing Finance Corporation voted to place its executive director, Mike DiNapoli, on paid leave for the second time in two months.

The decision was made to appease board member Meredith Ivey, a former DeSantis spokesperson who is now a deputy secretary of the Department of Commerce. Ivey said she needed more time to read the report, but blasted its contents and voiced support for DiNapoli.

“I personally do not have a high opinion at all of the inspector general report,” Ivey said. “It seems very sloppy, one-sided, read more like a media hit piece.”

The board also voted Friday to prohibit employees who spoke to the inspector general from being fired without cause. Ivey voted against it.

On Thursday, the corporation’s inspector general revealed the contents of a two-month investigation into DiNapoli, whose appointment by DeSantis in February has roiled the close-knit organization. The corporation is effectively a multibillion-dollar bank for the state, distributing hundreds of millions of affordable housing dollars each year and issuing bonds.

Employees of the corporation told investigators that DiNapoli screamed at staff, made sexist comments, talked about their weight and threatened their jobs.

“The conduct is severe and pervasive enough to create a work environment that a reasonable person would consider intimidating, hostile or abusive,” said the inspector general, Chris Hirst, on Thursday.

Since being appointed by DeSantis in February, 15 people — 10% of the corporation’s workforce — have quit or been fired by DiNapoli. Board members said they were concerned with so many people leaving, especially after the Legislature this year assigned a record $711 million to address the state’s affordable housing crisis.

“I really have a problem now with the toxic environment that’s left here,” board member Ron Lieberman, a homebuilder, said. “Especially after we’ve been given all the extra resources.”

Hirst also identified other concerns surrounding DiNapoli and his hiring.

DiNapoli is also on the board of the First Housing Development Corp. of Florida, which contracts with the corporation. Three of the corporation’s general counsels, who doubled as ethics officers, said it was a conflict of interests. Hirst agreed and concluded it was a violation of the corporation’s policies.

DiNapoli disagreed, telling Hirst it was a “gray line,” and “an appearance of a conflict is not a conflict,” Hirst said. One of those general counsels was later fired by DiNapoli.

DiNapoli also ordered the corporation’s chief financial officer, who manages the organization’s bond portfolio, to sell its Disney bonds — at a loss, Hirst said. DiNapoli said holding the bonds was a “bad look” because of the entertainment company’s ongoing dispute with DeSantis over control of its Orlando-area special taxing district.

Selling a bond at a loss for a non-financial reason appeared to be a violation of the corporation’s ethics policies, Hirst said.

The corporation also violated its hiring policy because it was supposed to advertise the executive director position, conduct interviews, do background checks and call work references. Aside from a criminal background check, none of that happened, Hirst said. The corporation doesn’t even have an application or a resume on file for DiNapoli, he added.

Instead, DiNapoli was simply appointed by DeSantis, with the only letter of recommendation coming from James Uthmeier, DeSantis’ chief of staff. Uthmeier is currently leading DeSantis’ campaign for president.

DiNapoli’s personal financial history could also pose a risk to the corporation, Hirst added.

DiNapoli was a longtime financial adviser in New York City until around 2015, when he lost his job with UBS. He filed for bankruptcy, debtors garnished his bank accounts and his Ocala home was foreclosed on.

Weeks after leaving UBS, a woman who claimed DiNapoli was her brother and her financial adviser filed a complaint alleging that DiNapoli “stole money from her account as well as forged her name to a check that was addressed to her and deposited those funds in another account.”

Hirst said the financial history brings “into question the subject, and therefore Florida Housing’s, ability to demonstrate it is a creditworthy institution, and that its principal owners and corporate officers are creditworthy individuals.” Those are requirements to do business with the Federal Housing Administration, Hirst noted.

The saga over DiNapoli has pitted DeSantis administration officials against the board members, nearly all of whom were appointed by DeSantis.

In July, board chairman Mario Facella put DiNapoli on paid administrative leave while Hirst’s investigation was ongoing. Two weeks ago, DeSantis reinstated DiNapoli, with a spokesperson for the governor saying the investigation had “found nothing to justify the placement of Mr. DiNapoli on administrative leave.”

After DiNapoli was reinstated, the corporation’s longtime human resources director quit, citing “the abuse and trauma of the last six months.” An outside lawyer hired to assist the board said Friday that state law did not permit the governor to reinstate DiNapoli or anyone else at the corporation, which is a separate entity from the state government.

On Thursday, DeSantis spokesperson Jeremy Redfern blasted the board as being the “deep state” and said the administration would “explore every available tool to ensure proper management and oversight of the board and its staff, including the Inspector General.”

“It’s clear to us that at least some members of this Board believe they can wield unchecked power to recklessly disparage a public official and tarnish his reputation without basic fairness and due process,” Redfern said in a statement. “The Board is clearly incapable of exercising prudent judgment.”

On Friday, Redfern said the board meeting confirmed his earlier statement: “It is clear to us that this board can barely function, has no grasp or understanding of basic laws, including due process, and has no ability to sort fact from fiction.”

Although other board members — and reporters — attended Thursday’s meeting, Ivey did not attend, and she said Friday that she wasn’t aware the board was going to be discussing the report.

Ivey cited no specific issues with the investigation, but she criticized it multiple times. She said she needed more time to review it, but when asked how much time she needed, she refused to say.

“My cursory review of the report, I have serious, serious concerns about the report,” Ivey said. “Frankly, I think it was sloppily conducted.”